|

|

So, what the hell is wrong in the world? If you are looking for the answer, you sure have come to the right place. Henry Ford knew exactly what the problem was in his day that is STILL the problem one hundred years later. But, be forewarned, the truth can be extremely difficult to bear. If given a choice, most people will choose a comforting delusion over an uncomfortable truth which ultimately is responsible for most of the suffering in the world - the endless wars and conflict, the poverty, the killing.

Henry

Ford was widely known for his pacifism during the first years of World War 1 , and for promoting anti-Semitism

(aka: the TRUTH)

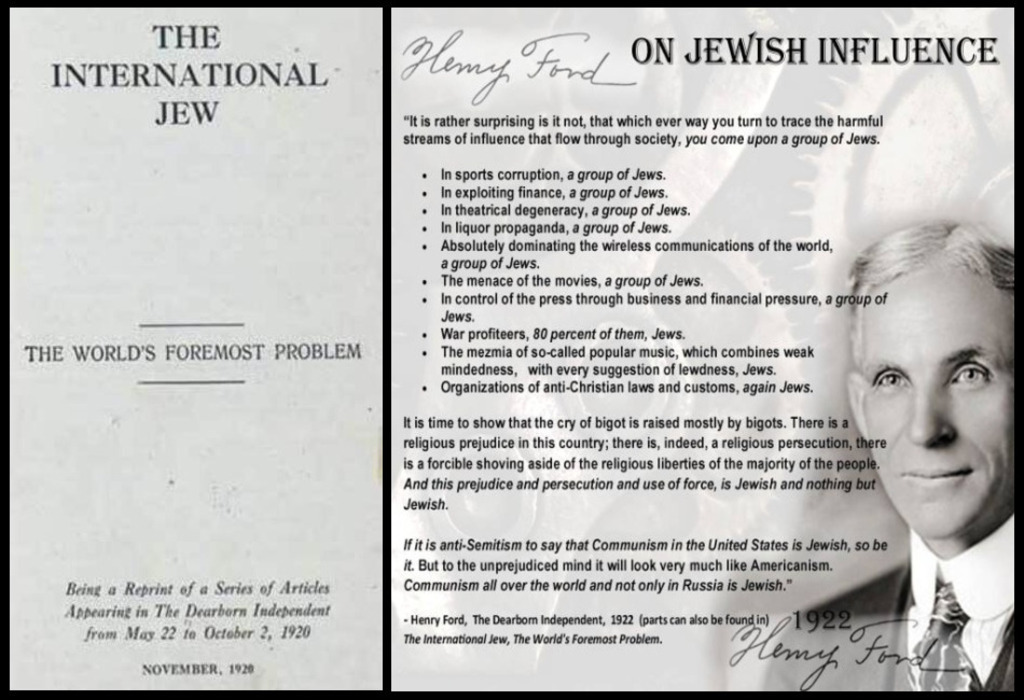

through his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent and his book, THE INTERNATIONAL JEW - THE

WORLD'S FOREMOST PROBLEM... _______________________ Volume 1: The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem (November, 1920)

Volume 3: Jewish Influences in American Life (November, 1921)

Volume 4: Aspects of Jewish Power in the United States (May, 1922)

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________  Typically

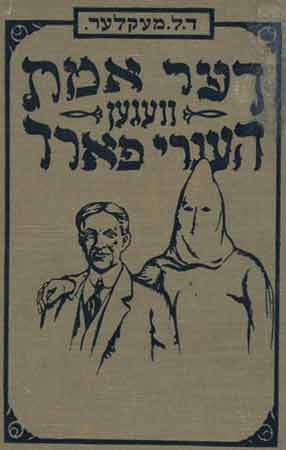

the Jews fired back at Ford with: "The Truth about Henry Ford" – New-York, In 1924. David Meckler

published the so called "exposé" of Ford in Yiddish which included

on its cover

a hooded Ku Klux Klansman with his arm casually and familiarly

draped over Henry Ford's shoulder, suggesting a friendly relationship between two men

sharing common anti-Semitic, nativist, and racist beliefs.

The Gentle Art of Changing Jewish NamesBy Henry Ford |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

HENRY ADAMS (1838-1918) Henry Adams of Massachusetts

was a prolific author, political journalist, historian and member of the Adams political family; descended from President John Adams (his great grandfather) and John Quincy Adams (his grandfather). He was a Harvard

graduate at a time when that still meant something. At

Harvard, Adams studied Greek and Roman literature, mathematics, government,

botany, astronomy, physics, and French. In 1894, Adams was elected president of the American Historical Association. He became widely

regarded as one of America's foremost intellectuals, again, at a time when the word "intellectual" still meant something. His posthumously-published memoirs, The Education of Henry Adams,won the Pulitzer Prize, and went on to be named by The Modern Libraryas the top English-language nonfiction book of the 20th century.

Adams's attitude towards Jews has been described as one of loathing. The noted American

statesman John Hay, remarking on Adams's "Anti-Semitism", said that when Adams

"saw Vesuvius (volcano in Italy) reddening... he searched for a Jew stoking the fire."

"I detest [the Jews], and everything connected with them, and I live only and solely with the hope of seeing their demise, with all their accursed Judaism. I want to see all the lenders at interest taken out and executed."

"We are in the hands of the Jews. They can do what they please with our values." Adams advised against investment except in the form of gold locked in a safe deposit box: "There you have no risk but the burglar. In any other form you have the burglar, the Jew, the Czar, the socialist, and, above all, the total irremediable, radical rottenness of our whole social, industrial, financial and political system." - Quotes by Henry Adams |

| ||||||||||

|

HENRY

FORD (1863-1947) By age 15, Henry Ford had taught himself how to dismantle and reassemble the timepieces of friends and neighbors, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. The mechanical and visionary genius became America's leading industrialist

and founder of the Ford Motor Company. Ford pioneered the development of the assembly line technique of mass production,

making cars affordable for the Middle Class. The increased

productivity enabled Ford to pay his workers unusually high wages.

During the 1920's, Ford published a series of essays

under the title "The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem.

"And if after having elected their man or group, obedience

is not rendered to the Jewish control, then you speedily hear of "scandals"

and "investigations" and "impeachments" for the removal of the

disobedient." "I know who caused the war

(World War I) - the Jewish bankers! I have the evidence here. Facts!" -

Quotes by Henry Ford | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

THOMAS EDISON (1847-1931) Edison

was the most prolific inventor of the 20th century. The "Wizard of Menlo Park" was also a first rate scientist and businessman. His creations include the stock ticker, battery for an electric car, phonograph, the motion picture camera, and

the light bulb. Edison is also credited with having created the first industrial

research laboratory, developing electrical power for

mass use (along with Tesla) and being awarded an incredible

1,093 U.S. patents. Edison

was a very close friend and vacation companion to the "anti-Semite" Henry Ford. Though actual quotes cannot be found, we learn from Jewish sources that

Edison did indeed share his buddy Ford's view of the "Big Jews".

The great genius struggled for many years to keep the

Jews from using his motion pictures without paying royalties. He eventually

lost any control he had to the Jews who would later establish Hollywood.

"Like

his friend Henry Ford, Edison was virulently anti-Semitic and blamed the Jews for all of the world's major

problems.". -

NNDB (Notable Names Data Base) . "(Israeli) Postal Authority officials were

red-faced yesterday upon learning that Thomas Edison, the famous inventor, who is to appear on an Israeli stamp to be issued soon, is believed

by some to have been an anti-semite. The Postal Authority - informed of these claims by The Jerusalem Post - began to launch an investigation yesterday into the charge. Alleging that Edison

was anti-Semitic are Stephen Esrati, a philatelic journalist in Ohio, and Ken Lawrence, vice President of the 56,000 member American Philatelic Society." . | ||||||||||

.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

A POUND (1885-1972) Ezra Pound was, without a doubt, the pre-eminent American poet of the 20th century. The literary legend actually mentored Ernest Hemingway,

TS Elliot, Robert Frost, and

other great writers. Pound's best-known works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920) and his unfinished

120-section epic, The Cantos. Having become disillusioned with America and England,

Pound moved to Mussolini's

Italy and also praised Hitler's achievements. Pound was never shy about expressing his feelings towards the Big Jews who he blamed for both

World Wars. “You let in the Jew and the Jew rotted your empire, and you yourselves out-jewed the Jew”

“And the big Jew has rotted every nation he has wormed into.”

“Your infamy is bound up with Judaea. You can not touch a sore or a shame in your empire but you find a Mond, a Sassoon, or a Goldsmid.” - Quotes by Ezra Pound | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

BOBBY FISCHER (1943-2008) Bobby Fischer was an

American chess grandmaster and World Chess Champion. He

is considered by many to be the greatest chess player who ever lived. Starting at age 14, he played in eight U.S.

Championships, winning each by at

least 1 point. At 15, Fischer became the youngest grandmaster and candidat e for the World Championship. Still only 20 years old,

he won the 1963-64 U.S. Championship

with the only perfect score in the history of the tournament. Fischer was very outspoken in his condemnation

of the Zionist conspirators controlling

America. Like Ezra Pound, Fischer also became an 'ex-pat', relocating to Japan.

"My main interest right now is to expose the Jews. This is a lot bigger than me. They're not just persecuting me. This is not just my struggle, I'm not just doing this for myself... This is life and death for the world. These God-damn Jews have to be stopped. They're a menace to the whole world." - Quote by Bobby Fischer | ||||||||||

ALEKSANDR

SOLZHENITSYN (1918-2008) Solzhenitsyn was not only a Russian novelist and noted historian, but

also a survivor of Stalin's Gulag. His Gulag Archipelago

remains an International Classic. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature

in 1970 and was finally expelled from the Soviet Union in 1974. He has been honored by some of the top universities in the West. Towards the end of his life, some of Solzhenitsyn's more controversial

"anti-Semitic" writings never saw the light of day in the West.

In "200 Years Together", and other

essays, the great writer cryptically alludes to a worldwide Jewish conspiracy behind the Bolshevist takeover and oppression of Russia.

"You must understand that the leading Bolsheviks who took over Russia were not Russians. They hated Russians. They hated Christians. Driven by ethnic hatred they tortured and slaughtered millions of Russians without a shred of human remorse.

More of my countrymen suffered horrific crimes at their blood stained hands than any people or nation ever suffered in the entirety of human history. It cannot be overstated. Bolshevism committed the greatest human slaughter of all time. The fact that most of the world is ignorant or uncaring about this enormous crime is proof that the global media is in the hands of its perpetrators." - Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn |

It was the "outside-of-the-box", creative genius of Adams, Ford, Edison,

Pound, Fischer and Solzhenitsyn that enabled them to clearly see "the big picture."