|

Medical Experimentation at Dachau

They All Did It Including Americans- Those Who Could, at Least

The onset and escalation of World War II provided the rationale for most of

Germany’s illegal human medical experimentation. Animal experimentation was known to be a poor substitute for experiments

on humans. Since only analogous inferences could be drawn from animal experiments, the use of human experimentation during

the war was deemed necessary to help in the German war effort. Applications for medical experimentation on humans were usually

approved on the grounds that animal tests had taken the research only so far. Better results could be obtained by using

humans in the medical experiments.[1] Inmates at the Dachau Concentration Camp were subjected to medical experimentation

involving malaria, high altitudes, freezing and other experiments. Such has been documented in the so-called Doctors’

Trial at Nuremberg, which opened on December 9, 1946, and ended on July 19, 1947. Also, Dr. Charles P. Larson, an American

forensic pathologist, was at Dachau and conducted autopsies, interviews, and a review of the remaining medical records to

determine the extent of the medical experimentation at the camp. Malaria

Experiments  Dr. Schilling at Trial The malaria experimentation

at Dachau was performed by Dr. Klaus Karl Schilling, who was an internationally famous parasitologist. Dr. Schilling was

ordered by Heinrich Himmler in 1936 to conduct medical research at Dachau for the purpose of immunizing individuals specifically

against malaria. Dr. Schilling admitted to Dr. Larson that between 1936 and 1945 he inoculated some 2,000 prisoners with

malaria. The medical supervisor at Dachau would select the people to be inoculated and then send this list of people to

Berlin to be approved by a higher authority. Those who were chosen were then turned over to Dr. Schilling to conduct the

medical experimentation.[2] At the Doctors’ Trial it was determined that Dr. Schilling’s experiments

were directly responsible for the deaths of 10 prisoners.[3] Dr. Charles Larson stated in his report concerning Dr. Schilling: It

was very difficult to know where to draw the line as to whether or not Dr. Schilling was a war criminal. Certainly he fell

into that category inasmuch as he had subjected people involuntarily to experimental malaria inoculations, which, even though

they did not produce many deaths, could very well have produced serious illness in many of the patients. He defended himself

by saying he did all this work by order from higher authority; in fact, Himmler himself. In my report, I wrote: “In view of all he has told me, this man, in my opinion, should be considered

a war criminal, but that he should be permitted to write up the results of his experiments and turn them over to Allied

medical personnel for what they are worth. Dr. Schilling is an eminent scientist of world-wide renown who has conducted a

most important group of experiments; their value cannot properly be ascertained until he has put them into writing for medical

authorities to study. The criminal acts have already been committed, and since they have been committed, if it were possible

to derive some new knowledge concerning immunity to malaria from these acts, it would yet be another crime not to permit

this man to finish documenting the results of his years of research.” But

my attempt to save Dr. Schilling’s life failed. Our High Command felt it had to make a public example of him—most

of the other high-ranking Nazis connected with Dachau had already been executed—and made his wife watch the

hanging. I did everything I could to stop it. I implored our military government not to pass sentence on him until

he’d had a fair hearing, because I was just beginning to win his confidence, and get through to him. Looking back,

I am sure that the execution of Dr. Schilling deprived the world of some very valuable scientific information—no matter

how distasteful his research and experimentation may have been.[4] Dr. Larson concluded in regard to Dr. Schilling: “…Dr.

Schilling, who was 72 [actually 74], should have lived. He never tried to run. He stayed in Dachau and made a full statement

of his work to me; he cooperated in every way, and was the only one who told the truth…”[5] The defense in the Doctors’ Trial at Nuremberg submitted evidence of doctors

in the United States performing medical experiments on prison inmates and conscientious objectors during the war. The evidence

showed that large-scale malaria experiments were performed on 800 American prisoners, many of them black, from federal penitentiaries

in Atlanta and state penitentiaries in Illinois and New Jersey. U.S. doctors conducted human experiments with malaria

tropica, one of the most dangerous of the malaria strains, to aid the U.S. war effort in Southeast Asia.[6] Although Dr. Schilling’s malaria experiments were no more dangerous or

illegal than the malaria experiments performed by U.S. doctors, Dr. Schilling had to atone for his malaria experiments by

being hanged to death while his wife watched. The U.S. doctors who performed malaria experiments on humans were never charged

with a crime. High-Altitude and Hypothermia Experiments

Germany also conducted high-altitude experiments at Dachau. Dr. Sigmund Rascher performed these experiments

beginning February 22, 1942 and ending around the beginning of July 1942.[7] The experiments were performed in order to know what happened to air crews after failure of, or ejection from, their pressurized

cabins at very high altitudes. In this instance, airmen would be subjected within a few seconds to a drop in pressure and

lack of oxygen. The experiments were performed to investigate various possible life-saving methods. To this end a low-pressure

chamber was set up at Dachau to observe the reactions of a human being thrown out at extreme altitudes, and to investigate

ways of rescuing him.[8] The victims were locked in the chamber, and the pressure in the chamber was then lowered to a level corresponding to very

high altitudes. The pressure could be very quickly altered, allowing Dr. Rascher to simulate the conditions which would

be experienced by a pilot freefalling from altitude without oxygen. Dr. Rascher

received authority to conduct these high-altitude experiments when he wrote to Heinrich Himmler and was told that prisoners

would be placed at his disposal. Dr. Rascher stated in his letter that he knew the experiments could have fatal results.

According to Walter Neff, the prisoner who gave testimony at the Doctors’ Trial, approximately 180 to 200 prisoners

were used in the high-altitude experiments. Approximately 10 of these prisoners were volunteers, and about 40 of the prisoners

were men not condemned to death. According to Neff’s testimony, approximately 70 to 80 prisoners died during these

experiments.[9] A film showing the complete sequence of an experiment, including the autopsy, was discovered in Dr. Rascher’s house

at Dachau after the war.[10] Dr. Rascher also conducted freezing experiments at Dachau after the high-altitude

experiments were concluded. These freezing experiments were conducted from August 1942 to approximately May 1943.[11] The purpose of these experiments was to determine the best way of warming German pilots who had been forced down in the

North Sea and suffered hypothermia. Dr. Rascher's subjects were forced to remain

outdoors naked in freezing weather for up to 14 hours, or the victims were kept in a tank of ice water for three hours.

Their pulse and internal temperature were measured through a series of electrodes. Warming of the victims was then attempted

by different methods, most usually and successfully by immersion in very hot water. It is estimated that these experiments

caused the deaths of 80 to 90 prisoners.[12] Dr. Charles Larson strongly condemned these freezing experiments. Dr. Larson wrote:

A Dr. Raschau [sic] was in charge of this work and…we found the records of his experiments.

They were most inept compared to Dr. Schilling’s, much less scientific. What they would do would be to tie up a prisoner

and immerse him in cold water until his body temperature reduced to 28 degrees centigrade (82.4 degrees Fahrenheit), when

the poor soul would, of course, die. These experiments were started in August, 1942, but Raschau’s [sic] technique

improved. By February, 1943 he was able to report that 30 persons were chilled to 27 and 29 degrees centigrade, their hands

and feet frozen white, and their bodies “rewarmed” by a hot bath…. They

also dressed the subjects in different types of insulated clothing before putting them in freezing water, to see how long

it took them to die.[13] Dr. Rascher and his hypothermia experiments at Dachau were not well

regarded by German medical doctors. In a paper titled “Nazi Science—The Dachau Hypothermia Experiments,”

Dr. Robert L. Berger wrote: Rascher was not well regarded in professional

circles…and his superiors repeatedly expressed reservations about his performance. In one encounter, Professor Karl

Gebhardt, a general in the SS and Himmler’s personal physician, told Rascher in connection with his experiments on

hypothermia through exposure to cold air that “the report was unscientific; if a student of the second term dared submit

a treatise of the kind [Gebhardt] would throw him out.” Despite Himmler’s strong support, Rascher was rejected

for faculty positions at several universities. A book by German scientists on the accomplishments of German aviation medicine

during the war devoted an entire chapter to hypothermia but failed to mention Rascher’s name or his work.[14] Blood-Clotting Experiments

Dr. Rascher also experimented with the effects of Polygal, a substance made from beet and apple pectin,

which aided blood clotting. He predicted that the preventive use of Polygal tablets would reduce bleeding from surgery and

from gunshot wounds sustained during combat. Subjects were given a Polygal tablet and were either shot through the neck

or chest, or their limbs were amputated without anesthesia. Dr. Rascher published an article on his use of Polygal without

detailing the nature of the human trials. Dr. Rascher also set up a company staffed by prisoners to manufacture the substance.[15] Dr. Rascher’s nephew, a Hamburg doctor, testified under oath that he knew of four prisoners who died from Dr. Rascher’s

testing Polygal at Dachau.[16] Obviously, Dr. Rascher’s medical experiments constitute major war crimes.

Dr. Rascher was arrested and executed in Dachau by German authorities shortly before the end of the war.[17] Infectious Diseases, Biopsies and

Salt-Water Tests Phlegmons were also induced in inmates at Dachau by intravenous

and intramuscular injection of pus during 1942 and 1943. Various natural, allopathic and biochemical remedies were then

tried to cure the resulting infections. The phlegmon experiments were apparently an attempt by National Socialist Germany

to find an antibiotic similar to penicillin for infection.[18] All of the doctors who took part in these phlegmon experiments were dead or had

disappeared at the time of the Doctors’ Trial. The only information about the number of prisoners used and the number

of victims was provided by an inmate nurse, Heinrich Stöhr, who was a political prisoner at Dachau. Stöhr stated

that seven out of a group of 10 German subjects died in one experiment, and that in another experiment 12 out of a group

of 40 clergy died.[19] Official documents and personal testimonies indicate that physicians at Dachau

performed many liver biopsies when they were not needed. Dr. Rudolf Brachtl performed liver biopsies on healthy people and

on people who had diseases of the stomach and gall bladder. While biopsy of the liver is an accepted and frequently used

diagnostic procedure, it should only be performed when definite indications exist and other methods fail. Some physicians

at Dachau performed liver biopsies simply to gain experience with its techniques. These Dachau biopsies violated professional

standards since they were often conducted in the absence of genuine medical indication.[20] The Luftwaffe had also been concerned since 1941 with the problem of shot-down

airmen who had been reduced to drinking salt water. Sea water experiments were performed at Dachau to develop a method of

making sea water drinkable through desalinization. Between July and September 1944, 44 inmates at Dachau were used to test

the desirability of using two different processes to make sea water drinkable. The subjects were divided into several groups

and given different diets using the two different processes.[21] During the experiments one of the groups received no food whatsoever for five to nine days. Many of the subjects became

ill from these experiments, suffering from diarrhea, convulsions, foaming at the mouth, and sometimes madness or death.[22] Most Deaths from Natural Causes Dr.

Charles Larson’s forensic work at Dachau indicated that only a small percentage of the deaths at Dachau were due to

medical experimentation on humans. His autopsies showed that most of the victims died from natural causes; that is, of disease

brought on by malnutrition and filth caused by wartime conditions. In his depositions to Army lawyers, Dr. Larson made it

clear that one could not indict the whole German people for the National Socialist medical crimes. Dr. Larson sincerely

believed that although Dachau was only a short ride from Munich, most of the people in Munich had no idea what was going

on inside Dachau.[23] Dr. Larson’s conclusions are reinforced by the book Dachau, 1933-1945:

The Official History by Paul Berben. This book states that the total number of people who passed through Dachau during

its existence is well in excess of 200,000.[24] The author concludes that while no one will ever know the exact number of deaths at Dachau, the number of deaths is probably

several thousand more than the quoted number of 31,951.[25] This book documents that approximately 66% of all deaths at Dachau occurred during the final seven months of the war.

The increase in deaths at Dachau was caused primarily by a devastating typhus epidemic which, in spite

of the efforts made by the medical staff, continued to spread throughout Dachau during the final seven months of the war.

The number of deaths at Dachau also includes 2,226 people who died in May 1945 after the Allies had liberated the camp,

as well as the deaths of 223 prisoners in March 1944 from Allied aerial attacks on work parties.[26] Thus, while illegal medical experiments were conducted on prisoners at Dachau, Berben’s book clearly shows that the

overwhelming majority of deaths of prisoners at Dachau were from natural causes. Allied Medical Experimentation Dr. Karl Brandt

and the other defendants were infuriated during the Doctors’ Trial at the moral high ground taken by the U.S. prosecution.

Evidence showed that the Allies had been engaged in illegal medical experimentation, including poison experiments on condemned

prisoners in other countries, and cholera and plague experiments on children.[27] Dr. Bettina Blome, the wife of the defendant Dr. Kurt Blome, meticulously researched

experiments that were conducted by the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) during the war. In addition

to malaria experiments on Terre Haute Federal Prison inmates, she also uncovered Dr. Walter Reed’s 19th-century

yellow fever research for the U.S. Army, in which volunteer human test subjects had died. Blome’s research was entered

into evidence at the Doctors’ Trial.[28] Defense attorney Dr. Robert Servatius expanded on the theme of U.S. Army human

experimentation. American journalist Annie Jacobsen writes: Servatius

had located a Life magazine article, published in June of 1945, that described how OSRD conducted experiments on 800 U.S.

prisoners during the war. Servatius read the entire article, word for word, in the courtroom. None of the American judges

was familiar with the article, nor were most members of the prosecution, and its presentation in court clearly caught the

Americans off guard. Because the article specifically discussed U.S. Army wartime experiments on prisoners, it was

incredibly damaging for the prosecution. “Prison life is ideal for controlled laboratory work with humans,”

Servatius read, quoting American doctors who had been interviewed by Life reporters. The idea that extraordinary times call

for extraordinary measures, and that both nations had used human test subjects during war, was unsettling. It pushed the

core Nazi concept of the Untermenschen to the side. The Nuremberg prosecutors were left looking like hypocrites.[29] The Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study was a controlled study of the effects of malaria on the prisoners of Stateville Penitentiary near Joliet, Illinois, beginning in the 1940s. The study was conducted by the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago in conjunction with the United States Army and the State Department. At the Nuremberg trials, Nazi doctors cited the precedent of the malaria experiments as part of their defense.[31][32] The study continued at Stateville Penitentiary for 29 years. In related studies from 1944 to 1946, Dr. Alf Alving,

a professor at the University of Chicago Medical School, purposely infected psychiatric patients at the Illinois State Hospital with malaria so that he could test experimental

treatments on them.[33] The

U.S. prosecution flew in Dr. Andrew Ivy to explain the differences in medical ethics between German and U.S. medical experiments.

Interestingly, Dr. Ivy himself had been involved in malaria experiments on inmates at the Illinois State Penitentiary. When

Dr. Ivy mentioned that the United States had specific research standards for medical experimentation on humans, it turned

out that these principles were first published on December 28, 1946. Dr. Ivy had to admit that the U.S. principles on medical

ethics in human experimentation had been made in anticipation of Dr. Ivy’s testimony at the Doctors’ Trial.[30] | Author(s): | John Wear | | Title: |

Medical Experimentation at Dachau |

| Sources: | Inconvenient

History, Vol. 11, No. 1 (2019) | | Dates: |

published: 2018-12-31,

first posted: 2019-01-01 03:41:43

|

__________________________________________________________________

The Clergy In Dachau: An Insight Into How The Allies Manufactured A Death Camp

CLERGY IMPRISONED IN DACHAU

AND POST LIBERATION Dachau was used as a detainment

facility for Christian clergy in Europe. In 1940 there were more than 1,000 clergymen in Dachau, which was about 4% of the

inmates in Dachau that year. After 1940 all priests imprisoned by Germany were relocated to Dachau, with a total of 2,762

clergymen imprisoned in Dachau by the end of the war. Catholics made up 2,579 of this total, while the rest were mostly

Protestant ministers.[1] The largest national contingent

was from Poland (1,780, or 64%), with the Germans (447, or 16%) and other nationalities following far behind. The clergymen

were housed in barracks nos. 26, 28 and 30 in the northwest corner of the camp. They were initially allowed to convert one

room of barrack 26 into a chapel, but after 1941 the Polish priests in barrack 28 were barred from using this chapel.[2] This article will examine some

of the mistreatment and crimes committed against the clergymen in Dachau. It will also examine the hardships suffered by

Dachau clergymen after the war, as well as the positive benefits from their internment in Dachau. Dachau was used as a detainment facility for Christian

clergy in Europe who were opposed to the policies of the NSDAP. This came at a time when Germany was increasingly alarmed

by the staggering scale of preparations by the Soviet Union to create the greatest offensive army ever

known. Source. MEDICAL EXPERIMENTATION Dachau was

used as a center for medical experimentation on humans involving malaria, high altitudes, freezing, phlegmon and other experiments.

This has been corroborated by hundreds of documents and by witnesses in the Doctors’ Trial at Nuremberg, which opened on December 9, 1946, and ended on July 19, 1947.[3] The malaria experimentation

at Dachau was performed by Dr. Klaus Karl Schilling, who was an internationally famous parasitologist. Dr. Schilling was

ordered by Heinrich Himmler in 1936 to conduct medical research at Dachau for the purpose of specifically immunizing individuals

against malaria. The medical supervisor at Dachau would select the people to be inoculated and then send this list of people

to Berlin to be approved by a higher authority. Those who were chosen were then turned over to Dr. Schilling to conduct

the medical experimentation.[4] A total of 176 Polish priests,

four Czechs and five German clergymen were subject to malaria experimentation at Dachau. Two priests died as a result of

these malaria experiments: Father Josef Horky from Czechoslovakia, and Father Francis Dachtera from Poland. It is also possible

that other clergymen died from indirect pathologies such as tuberculosis or renal failure induced by these malaria experiments.[5] American malaria experiments on prisoners. Although

Dr. Schilling’s malaria experiments were no more dangerous or illegal than the malaria experiments performed by U.S.

doctors, Dr. Schilling had to pay for his malaria experiments by being hanged to death while his wife watched. The

U.S. doctors who performed malaria experiments on humans were never charged with a crime. Source. Phlegmons were induced in inmates at Dachau by intravenous and intramuscular injection of pus. Various natural,

allopathic and biochemical remedies were then used to attempt to cure the resulting infections. The phlegmon experiments

were conducted by National Socialist Germany to find an antibiotic similar to penicillin for the infection.[6] A total of 40 clergymen in Dachau were subject to phlegmon experiments. Eleven out of this group died, and some of

the survivors suffered adverse health effects from these experiments.[7] Another Catholic priest who

had survived malaria experimentation, Father Leo Michalowski, was selected to undergo tests of his resistance to immersion

in ice water. Although Michalowski survived this experiment, it left him with a weak heart for the rest of his life.[8] TYPHUS The first typhus epidemic at Dachau began in December 1942. Quarantine

measures were taken to prevent its spread. The end of this typhus epidemic was declared on March 14, 1943, with the disease

killing between 100 and 250 inmates in the camp.[9] The second typhus epidemic

struck Dachau in December 1944 and was much more widespread. This outbreak of endemic typhus caused the 15 blocks in the

eastern part of the camp to be isolated from the rest of the camp. Many of the priests in Dachau volunteered to alleviate

the sufferings of the sick inmates any way they could. These volunteers were all contaminated by typhus, and most of them

died as a result.[10] Typhus was the primary reason

for the huge piles of dead bodies at Dachau when U.S. troops entered the camp. Dr. Charles P. Larson, an American forensic

pathologist, was at Dachau and conducted hundreds of autopsies at Dachau and some of its sub-camps. Dr. Larson stated in

regard to these autopsies: Many of them died from typhus. Dachau’s crematoriums couldn’t keep up with the burning of the bodies.

They did not have enough oil to keep the incinerators going. I found that a number of the victims had also died from tuberculosis.

All of them were malnourished. The medical facilities were most inadequate. There was no sanitation…”[11]

Dr. John E. Gordon, M.D.,

Ph.D., a professor of preventive medicine and epidemiology at the Harvard University School of Public Health, was with U.S.

forces at the end of World War II. Dr. Gordon determined that disease, and especially typhus, was the number one cause of

death in the German camps. Dr. Gordon explained the causes for the outbreaks of disease and typhus: Germany in the spring months of April and May [1945] was

an astounding sight, a mixture of humanity traveling this way and that, homeless, often hungry and carrying typhus with

them… Germany was in chaos. The destruction of whole cities and the path

left by advancing armies produced a disruption of living conditions contributing to the spread of disease. Sanitation was

low grade, public utilities were seriously disrupted, food supply and food distribution was poor, housing was inadequate

and order and discipline were everywhere lacking. Still more important, a shifting of population was occurring such as few

times have experienced.[12]

Bombed out and nowhere to go. “160 German cities

and towns were destroyed by British and American bombing raids. This was done to “terrorize” the German

people. Destroying these cities served no military purpose and did not shorten the war by a single day. The purpose was to

destroy Germany and kill as many Germans as possible.” (Source) FAMINE The

food rations received by inmates in German concentration camps decreased in May 1942 due to shortages caused by the bogged-down

German war effort. These shortages became a famine which reached its nadir in midsummer 1942. The weight of the clergymen

in Dachau dropped substantially due to the inadequate food supply.[13] The death rate in Dachau rose substantially, and the clergy did not escape this general misery.[14] Conditions began to improve

in Dachau when Martin Weiss became camp commandant in August 1942. Paul Berben wrote: From November [1942] food parcels could be sent to clergy

and the food situation improved noticeably. Germans and Poles particularly received them in considerable quantities from

their families, their parishioners and members of religious communities. In Block 26 100 [parcels] sometimes arrived on

the same day. This all bore witness to the continuing feeling of Christian fellowship which survived all persecution…

This period of relative plenty lasted till the end of 1944 when the disruption of communications stopped

the dispatch of parcels. Nevertheless, the German clergy continued to receive food through the Dean of Dachau, Herr Pfanzelt,

to whom the correspondents sent food tickets…[15]

As the Allies closed in

on the center of Germany toward the end of the war, large numbers of prisoners were evacuated from camps near the front

and moved to the interior. Dachau, being centrally located, was a key camp for these transfers. So while food became more

difficult to obtain, the demand for food increased with the transfer of prisoners from other camps. This resulted in major

food shortages at Dachau and a major increase in deaths in the camp near the end of the war.[16] Approximately 66% of all deaths at Dachau occurred during

the final seven months of the war. Source. POLISH PRIEST DEATHS The book The

Priest Barracks Dachau, 1938-1945 states that National Socialist Germany was intent on killing the Polish elite.[17] This book claims that 868 out of 1,780 Polish priests died during their internment in Dachau. This death rate of over

48% of the Polish priests in Dachau is supported by a book written by Johann Neuhäusler, who was interned in Dachau

from July 1941 to April 1945.[18] Neuhäusler’s book

used a table indicating that 868 out of 1,780 Polish priests and 166 out of 940 non-Polish clergymen died in Dachau. However,

Neuhäusler’s book did not reference where the figures in his table were obtained. Moreover, Neuhäusler wrote

that as a “special prisoner” separated from the general camp, he could not learn all that happened in Dachau.

Neuhäusler’s statistics did not originate from his personal experience in Dachau.[19] Neuhäusler’s statistics

contradict what Jewish historian Harold Marcuse writes about the survival rate of Polish priests in Dachau: The 2,579 Catholic clergymen

imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp had been a special group among the camp inmates. We recall that in 1940 all

of the Christian clergymen being held in “protective custody” in the Reich—about 1,000 at that time—were

consolidated in Dachau…About 450 of the final number were German or Austrian (the Poles with 1,780 were the largest

national group), and they had a relatively high survival rate.[20]

In his book Dachau,

1933-1945: The Official History, Paul Berben used Neuhäusler’s table indicating that 868 out

of 1,780 Polish priests in Dachau died.[21] Berben wrote that some 500 Polish clergy, most of them elderly, arrived in Dachau by train in deplorable condition

on October 29, 1941. Berben said that this group was not issued adequate winter clothes, and that only 82 survived

their internment in Dachau.[22] Zeller writes that more than 300 of these mostly elderly disabled Polish clergymen were sent to the gas chamber at

Hartheim Castle in Austria.” (Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco,

CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 162-165.) Berben also wrote that 304 members of the Polish clergy were exterminated in various ways, including “liquidated

inside the camp, in the showers or in the Bunker.”[23] Berben did not explain how Polish priests could have been exterminated in the showers in Dachau. Historians and former

Dachau inmates generally agree that there were no functioning gas chambers inside Dachau.[24]Berben in his own book even stated that “the Dachau gas-chamber was never operated.”[25] Peter Winter states: The interior of the Dachau

“gas chamber” as presented to tourists in 2010. The floor contains four drains, directly connected to the other

rooms in the building (two of which are visible in this picture). This feature alone would have made “gassings”

in the room impossible, as poisonous gas would have leaked throughout the structure and killed everyone else, SS guards

included. DACHAU CLERGY MISTREATED AFTER LIBERATION The Americans who liberated Dachau were intent on exploiting Dachau for propaganda purposes. Photographers repeatedly

visited Dachau to take pictures and film newsreel footage of the dead. Some clergymen petitioned American authorities to

improve their lot. For example, Father Michel Riquet protested in a letter to Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, commander-in-chief

of the Allied forces: You will understand our impatience and even our astonishment at the fact that, more than 10 days after greeting

our liberators, the 34,000 detainees of Dachau are still prisoners of the same barbed-wire fences, guarded by sentinels

whose orders are still to fire on anyone who attempts to escape—which for every prisoner is a natural right, especially

when he is told that he is free and victorious. In the barracks that are visited every day by the international press, some

men continue to stagnate, stacked in these triple-decker beds that dysentery turns into a filthy cesspool, while the lanes

between the blocks continue to be lined with cadavers—135 per day—just like in the darker times of the tyranny

that you conquered.[26]

The German clergymen who

left Dachau also discovered that Germans were facing severe deprivations and starvation after the war. German Protestant

Church president and former Dachau prisoner Martin Niemöller said to an American audience when he toured the United

States from December 1946 to April 1947: The offices of our [American] military government are very nicely and cozily heated and our military government

people live a good life as far as nourishment and everything else, even housing, is concerned. But they don’t know

how people really think and react who are hungry, who are on the way to starving.

In the U.S. sector of Berlin, the infant mortality rate

for infants born in the summer of 1945 was 95%. Source. Under President Eisenhower’s directions even essential Red Cross food parcels were denied to starving German POW’s.

Instead of being re-distributed to starving Displaced Persons in the American sector, the U.S. Army was under orders to “To Stockpile It! Reject It! Burn It! “No one of German race was allowed any help by

the United Nations… The new untouchables were thrown into Germany to die, or survive as paupers in the miserable

accommodations which the bombed-out cities of Germany could provide…” Source. Niemöller claimed that Germans were receiving no better than “the lowest ration ever heard of in a Nazi

concentration camp.”[27] Although Niemöller raised

more money than expected from his American tour, he was disappointed in its outcome because he was not able to improve U.S.

occupation policies in Germany. After months in America, Niemöller’s return to war-ravaged Germany came as a shock.

Niemöller wrote to Pastor Ewart Turner: The winter is over, but you feel it everywhere—in the cold which is still harboring in the rooms, especially

in this old castle with its thick stone walls. The water pipes are broken. No running water in kitchen or toilet. Sitting

at my desk I shiver from cold even now, and the only place where I feel some relief is once again in the bed. The food situation

is more than difficult, and I scarcely dare to take a slice of bread, thinking that Hertha, Tini, and Hermann [his children]

are far more in need of having it than I, and I can’t help feeling guilty for being so well fed [in the United States].

The whole aspect of life is grim and dark; you see the traces of progressive starvation in every face you come to see.[28]

The physical and emotional

toll of hunger, cold and disillusionment made life in Germany intolerable for Niemöller. Niemöller’s wife

Else bemoaned when they got back to Germany from America, “It was so much easier there than here.” Niemöller

told Pastor Turner that if things didn’t improve, “I should prefer to be back in my cell number 31 at Dachau.”

Niemöller blamed “the followers of the Morgenthau Plan” who had moved their “headquarters from Washington

to the American Zone.”[29] In another letter to Turner

in the fall of 1947, Niemöller wrote: The [coming] winter will be a very severe test for all of us. The rations in fat and meat have been cut again to

25 grams of butter and 100 grams of meat a week! And no potatoes. The normal consumer probably will die this winter, and

that Jew [in the occupation forces] will have been right who answered my question, what would become of the too many people

in the Western Zones, by saying: “Don’t worry, we shall look after that and the problem will be solved

in quite a natural way!”

Niemöller understood the Jewish official’s phrase “a natural way” to mean death by starvation.[30] Propaganda: German civilians and “fresh”

troops were often required to view dead bodies in the Concentration Camps. Bodies were even exhumed for grotesque display.

Many of these fresh troops had not participated in nor witnessed the ravages of WWII or the plagues of typhus and dysentery

that swept Germany and other nations suffering the loss of basic utilities like clean water, food & medicine from saturation

bombing that continued after General Patton was stopped twice from taking Berlin. POSITIVE ASPECTS OF DACHAU INTERNMENT Many clergymen in Dachau came to view their imprisonment in Dachau as a positive experience. Father Leo de Coninck

summarized his stay in Dachau: “Three years of experiences that I would not have missed for anything in the world.”

While Father de Coninck’s statement may be surprising, his statement recurs in the testimonies of many clergymen imprisoned

in Dachau.[31] Martin Niemöller, for

example, had some fond memories of Dachau. On his speaking tour in America, Niemöller recalled sharing quarters with

three Catholic priests in Dachau and praying together “according to the Roman customs every morning, every noontime,

and every night.” Niemöller said: “We became brethren in Christ not only by praying together but by common

listening to the Word of God.” Without fail, Niemöller told the story of his international and multi-denominational

congregation on Christmas Eve 1944 in Dachau.[32] Catholic Bishop Johannes Neuhäusler

also preferred not to think about his bad experiences in Dachau. Neuhäusler said: “I prefer to speak about the

nice memories associated with the name Dachau,” such as the ecumenical Bible readings in the camp, and the Christmas

tree the SS set up for prisoners in 1941.[33] Father Maurus Münch said:

“Dachau was, in the designs of Providence, the cradle of ecumenism lived out completely. Never in the history of the

people of God had there been so many secular and religious priests of all Christian confessions, [who were] united in a community

of life and suffering, as during the great witness of Dachau.” While Catholic priests made up the vast majority of

clergymen in Dachau, they established friendly and fraternal relations with Protestant pastors and clergymen of other faiths.[34] Dachau became a laboratory

for ecumenical dialogue. Father Münch wrote: In Dachau, we were united fraternally in the breath of the Holy Spirit, strengthened in Christ to serve Him behind

the watchtowers, the electrified fences and the barbed wire. We sought unity in our discussions and our dialogues….In

authentic fraternity and common prayer, we laid the foundations for new relations between the different churches….The

priests in Dachau and the Christian laymen took home with them, to their churches and their families, the lived experience

of unity.[35]

CONCLUSION Harold Marcuse states that the most reliable figures today set the total

number of inmates in Dachau at 206,206, of whom at least 31,591 are documented to have died or been killed prior to liberation.[36] Paul Berben wrote that the total number of people who passed through Dachau during its existence is well in excess of

200,000.[37] Berben concluded that while no one will ever know the exact number of deaths at Dachau, the number of deaths is probably

several thousand more than the quoted number of 31,951. [38] Berben documented that approximately

66% of all deaths at Dachau occurred during the final seven months of the war. The increase in deaths at Dachau was caused

primarily by a devastating typhus epidemic which, in spite of the efforts made by the medical staff, continued to spread

throughout Dachau. The number of deaths at Dachau also includes 2,226 people who died in May 1945 after the Allies had liberated

the camp, as well as the deaths of 223 prisoners in March 1944 from Allied bombings of Kommandos.[39] Based on these statistics,

less than 17% of the inmates died in Dachau before, during and after World War II. The vast majority of these deaths, including

the deaths of European clergymen in Dachau, were from natural causes.

Establishment historians characterize National

Socialist Germany as a uniquely barbaric, vile and criminal regime that was totally responsible for starting World War II

and carrying out some of the most heinous war crimes in world history. Germany’s War by John Wear

refutes this characterization of Germany, bringing history into accord with the facts. Discover more about Germany’s

War and purchasing options here. ENDNOTES

1] Kater, Michael H., Doctors under Hitler, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989, p. 226.

[2] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 64-65.

[3] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 125.

[4] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 66-67.

[6] Schmidt, Ulf, Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor, New York: Continuum Books, 2007, p. 376. [7] Spitz, Vivien, Doctors from Hell: The Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans, Boulder, Colo.: Sentient Publications,

2005, p. 74. [8] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 126.

[11] Spitz, Vivien, Doctors from Hell: The Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans, Boulder, Colo.: Sentient Publications,

2005, p. 85. [12] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 133.

[13] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 67-68.

[14] Michalczyk, John J., Medicine, Ethics, and the Third Reich: Historical and Contemporary Issues, Kansas City,

Mo.: Sheed & Ward, 1994, p. 96. [16] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, pp. 133-134.

[17] Ibid., p. 134. See also Michalczyk, John J., Medicine, Ethics, and the Third Reich: Historical and Contemporary

Issues, Kansas City, Mo.: Sheed & Ward, 1994, p. 97.

[18] Pasternak, Alfred, Inhuman Research: Medical Experiments in German Concentration Camps, Budapest, Hungary: Akadémiai

Kiadó, 2006, p. 149. [21] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, pp. 136-137.

[22] Spitz, Vivien, Doctors from Hell: The Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans, Boulder, Colo.: Sentient Publications,

2005, p. 173. [23] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, p. 69.

[24] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 19.

[27] Schmidt, Ulf, Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor, New York: Continuum Books, 2007, p. 376. [28] Jacobsen, Annie, Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America, New

York: Little, Brown and Company, 2014, pp. 273-274. [30] Schmidt, Ulf, Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor, New York: Continuum Books, 2007, pp. 376-377. [1] Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 43-44, 222. [2] Ibid., p. 44. [3] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 123. [4] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 64-65. [5] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp.

152-154. [6] Pasternak, Alfred, Inhuman Research: Medical Experiments in German Concentration Camps, Budapest, Hungary:

Akadémiai Kiadó, 2006, p. 149. [7] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp.

157-158. [8] Ibid., p. 158. [9] Ibid., pp. 124-125. [10] Ibid., pp. 126-132; Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration

Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 232. [11] McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, WA.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 60-61. [12] Gordon, John E., “Louse-Borne Typhus Fever in the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, 1945,” in

Moulton, Forest Ray, (ed.), Rickettsial Diseases of Man, Washington, D.C.: American Academy for the Advancement

of Science, 1948, pp. 16-27. Quoted in Berg, Friedrich P., “Typhus and the Jews,” The Journal of Historical

Review, Winter 1988-89, pp. 444-447, and in Butz, Arthur Robert, The Hoax of the Twentieth Century, Newport

Beach, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 46-47. [13] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, p.

107. [14] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 150. [15] Ibid., p. 151. [16] Cobden, John, Dachau: Reality and Myth in History, Costa Mesa, CA: Institute for Historical Review, 1991,

pp. 21-23. [17] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, p.

11. [18] Ibid., pp. 18, 258. [19] Neuhäusler, Johannes, What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?, Dachau: Trustees for

the Monument of Atonement in the Concentration Camp at Dachau, 1973, pp. 3, 25-26. [20] Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 221. [21] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 277. [22] Ibid., p. 148. [23] Ibid., pp. 148-149. [24] For example, Neuhäusler, Johannes, What was it like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?, Dachau:

Trustees for the Monument of Atonement in the Concentration Camp at Dachau, 1973, pp. 15, 29. [25] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 8. [26] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, p.

212. [27] Hockenos, Matthew D., Then They Came For Me: Martin Niemöller, The Pastor Who Defied the

Nazis, New York: Basic Books, 2018, p. 204. [28] Ibid., p. 212. [29] Ibid. [30] Ibid., p. 213. [31] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, p.

217. [32] Hockenos, Matthew D., Then They Came For Me: Martin Niemöller, The Pastor Who Defied the

Nazis, New York: Basic Books, 2018, p. 203. [33] Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 229. [34] Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp.

222-223. [35] Ibid., pp. 223-224. [36] Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 70. [37] Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945, The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 19. [38] Ibid., p. 202. [39] Ibid., pp. 95, 281.

________________________________________________ The 13 Most Evil US Government Human Experiments The U.S. Government has been caught conducting an insane amount of vile, inhumane and grisly experiments on humans

without their consent and often without their knowledge. So in light of recent news of the U.S. infecting Guatemalans with

STDs, here are the 13 most evil, for lack of a better word, cases of human-testing as conducted by the United States of

America. Get

ready to become one of those conspiracy theory nuts, because after this list, you will never fully trust your government

again. 1. Project MKULTRA, Subproject 68 The CIA-ran Project MKULTRA paid Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron for Subproject 68, which would be experiments involving mind-altering substances.

The entire goal of the project was to probe examination into methods of influencing and controlling the mind and being able

to extract information from resisting minds.

So in order to accomplish this, the doctor took patients admitted to his Allen

Memorial Institute in Montreal and conducted “therapy” on them. The patients were mostly taken in for issues

like bi-polar depression and anxiety disorders. The treatment they received was life-altering and scarring. In the period he

was paid for (1957-1964) Cameron administered electroconvulsive therapy at 30-40 times the normal power. He would put patients

into a drug-induced coma for months on-end and playback tapes of simple statements or repetitive noises over and over again. The victims forgot

how to talk, forgot about their parents, and suffered serious amnesia. And all of this was performed on Canadian citizens because the CIA

wasn’t willing to risk such operations on Americans. To ensure that the project remained funded, Cameron, in one scheme,

took his experiments upon admitted children and in one situation had the child engage in sex with high-ranking government

officials and film it. He and other MKULTRA officers would blackmail the officials to ensure more funding. 2.

Mustard Gas Tested on Soldiers via Involuntary Gas Chambers

As bio-weapon research intensified in the 1940’s, officials also began

testing its repercussions and defenses on the Army itself. In order to test the effectiveness of various bio-weapons, officials

were known to have sprayed mustard gas and other skin-burning, lung-ruining chemicals, like Lewisite, on soldiers without

their consent or knowledge of the experiment happening to them. They also tested the effectiveness of gas masks and protective

clothing by locking soldiers in a gas chamber and exposing them to mustard gas and lewisite, evoking the alleged gas chamber

image of Nazi Germany. EFFECTS OF LEWISITE: Lewisite is a gas that can easily penetrate clothing and even rubber. Upon contact with

the skin, the gas immediately causes extreme pain, itching, swelling and even a rash. Large, fluid-filled blisters develop

12 hours after exposure in the form of intensely severe chemical burns. And that’s just skin contact with the gas. Inhaling of the

gas causes a burning pain in the lungs, sneezing, vomiting, and pulmonary edema. EFFECTS OF MUSTARD GAS: Symptomless

until about 24 hours after exposure, Mustard Gas has mutagenic and carcinogenic properties that have killed many subjected

to it. Its

primary effects include severe burns that turn into yellow-fluid-leaking boils over a period of time. Although treatment

is available, Mustard Gas burns heal very, very slowly and are extremely painful. The burns the gas leaves on the skin are sometimes

irreparable. It was also rumored that along with the soldiers, patients at VA hospitals were being used as guinea pigs for medical

experiments involving bio-warfare chemicals, but that all experiments were changed to be known as “observations”

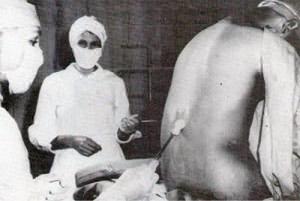

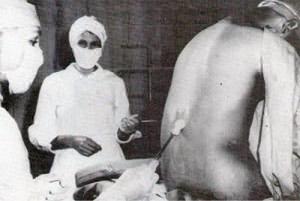

to ward off suspicions. 3. U.S. Grants Immunity to Involuntary-Surgery

Monster

As head of Japan’s infamous Unit 731 (a covert biological and chemical

warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II), Dr. Shiro Ishii (head of medicine) carried out violent human experimentation of tens of thousands during the Second Sino-Japanese

War and World War II.

Ishii was responsible for testing vivisection techniques without any anesthesia

on human prisoners. For the uninitiated, vivisection is the act of conducting experimental surgery on living creatures (with

central nervousness) and examining their insides for scientific purposes. So basically, he was giving unnecessary surgery to prisoners by opening

them all the way up, keeping them alive and not using any anesthetic. During these experiments he would also force pregnant women to abort

their babies. He also played God by subjecting his prisoners to change in physiological conditions and inducing

strokes, heart attacks, frost bite, and hypothermia. Ishii considered these subjects “logs”. Following imminent defeat in 1945, Japan

blew up the Unity 731 complex and Ishii ordered all the remaining “logs” to be executed. Not soon after, Ishii was arrested. And then,

the respected General Douglas McArthur allegedly struck a deal with Ishii. If the U.S. granted

Ishii immunity from his crimes, he must exchange all germ warfare data based on human experimentation. So Ishii got away with his crimes because the

US became interested in the results of his research.

While not directly responsible for these acts, the actions of the American

government certainly illustrated it was more than willing to condone human torture for advancements in biological warfare

that could kill even more people. Not a surprise, considering its past resume. Ishii remained alive until 1959, performing research

into bio-weaponry and probably thinking up more plans to annihilate people in different, Dr. Giggles-esque ways to his dying

day. 4. Deadly Chemical Sprays on American Cities

Showing once again that the U.S. always tends to test out worse-case scenarios

by getting to them first and with the advent of biochemical warfare in the mid 20th century, the Army, CIA and government

conducted a series of warfare simulations upon American cities to see how the effects would play out in the event of an

actual chemical attack. They conducted the following air strikes/naval attacks: - The CIA released a whooping cough virus

on Tampa Bay, using boats, and so caused a whooping cough epidemic. 12 people died.

- The Navy sprayed San Francisco with bacterial pathogens and in consequence many citizens

developed pneumonia.

- Upon Savannah,

GA, and Avon Park, FL, the army released millions of mosquitoes in the hopes they would spread yellow fever and dengue fever.

The swarm left Americans struggling with fevers, typhoid, respiratory problems, and the worst, stillborn children.

Even worse

was that after the swarm, the Army came in disguised as public health workers. Their secret intention the entire time they were

giving aid to the victims was to study and chart-out the long term effects of all the illnesses they were suffering.

5. US Infects Guatemalans With STDs

To do this, they used infected prostitutes and let them loose on unknowing prison inmates, insane asylum patients

and soldiers. When spreading the disease through

prostitution didn’t work as well as they’d hoped, they instead went for the inoculation route. Researchers poured syphilis bacteria onto men’s

penises and on their forearms and faces. In some cases, they even inoculated the men through spinal punctures. After all the infections

were transmitted, researchers then gave most of the subjects treatment, although as many as 1/3 of them could have been

left untreated, even if that was the intention of the study in the first place. On October 1, 2010, Hillary Clinton apologized for the events and new research has gone on to see if anyone affected is still alive and afflicted

with syphilis. Since many subjects never got penicillin, its possible and likely that someone spread it to future generations. 6. Human Experiments to Test the Effects of The Atomic Bomb While testing out and trying to harness the

power of the atomic bomb, U.S. scientists also secretly tested the bomb’s effects on humans. During the Manhattan Project, which gave way to the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, U.S. scientists resorted to secret human testing

via plutonium injection on 18 unsuspecting, non-consenting patients. This included injecting soldiers with micrograms of plutonium for

Project Oak Ridge along with later injecting three patients at a Chicago hospital. Imagine you’re an admitted patient, helpless

in a hospital bed, assuming that nothing is wrong when the government suddenly appears and puts weapons-grade plutonium

in your blood. Out of the 18 patients, who were known only by their code-names and numbers at the time, only 5 lived longer than

20 years after injection. Along with plutonium, researchers also had fun with uranium. At a Massachusetts hospital, between 1946 and 1947,

Dr. William Sweet injected 11 patients with uranium. He was funded by the Manhattan Project. And in exchange

for the uranium he received from the government, he would keep dead tissue from the body of the people he killed for scientific

analysis on the effects of uranium exposure. 7. Injecting Prisoners

with Agent Orange Agent Orange While

he received funding from the Agent Orange producing Dow Chemical Company, the US Army, and Johnson & Johnson, a psychopathic

JEW Dr. Albert Kligman used prisoners as subjects in what was deemed “dermatological research”. The dermatology

aspect was testing out product the effects of Agent Orange on the skin. Needless to say the injecting of, or exposure

to, dioxin is beyond monstrous to voluntarily do to any human. Kligman, though, injected dioxin (a main component of Agent Orange) into the prisoners to study its effects. What did happen was that the prisoners developed an eruption of chloracne (all that stuff from high school combined with blackheads and cysts and pustules that looked like the picture shown to

the left) that develop on the cheeks, behind the ears, armpits, and the groin — yes, the groin. Kligman was rumored to have injected 468 times

the amount he was authorized to. Documentation of that effect has, wisely, not been distributed. The Army oversaw while Kligman continued to test

out skin-burning chemicals to (in their words) “learn how the skin protects itself against chronic assault from toxic

chemicals, the so-called hardening process” and test out many products whose effects were unknown at the time, but

with the intent of figuring that out. During these proceedings, Kligman was reported to have said: “All I saw before me

were acres of skin… It was like a farmer seeing a fertile field for the first time.” Using that analogy,

it’s easy to see how he could plow straight through so many human subjects without an ounce of sympathy. 8. Operation Paperclip

While the Nuremberg trials were being conducted and the ethics and rights of

humanity were under investigation, the U.S. was secretly taking in Nazi scientists and giving them American identities. Under Operation Paperclip, named so because of the paperclips used to attach the scientists’ new profiles to their US personnel pages, N***s

who had worked for in the infamous human experiments (which included surgically grafting twins to each other and making

then conjoined, removing nerves from people’s bodies without anesthetic, and testing explosion-effects on them) in

Germany brought over their talents to work on a number of top secret projects for the US. Given then-President Truman’s anti-Nazi

orders, the project was kept under wraps and the scientists received faked political biographies, allowing these monsters

to live on not only American soil, but as free men.

So while it was not direct experimentation, it was the U.S. taking some of

the alleged worst people in the world and giving them jobs here to do unknown, horrible experiments/research. Eugen Saenger on the right from Werner von Braun (center) in Austria on May 3, 1945,

after surrender to American troops. 9. Infecting Puerto Rico With

Cancer

In 1931, Dr. Cornelius (that’s right, Cornelius) Rhoads

was sponsored by the Rockefeller Institute to conduct experiments in Puerto Rico. He infected Puerto Rican citizens with cancer cells, presumably to study the effects. Thirteen of them died. What’s most striking is that the accusations stem from a note

he allegedly wrote: “The Porto Ricans (sic) are the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish

race of men ever to inhabit this sphere… I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off

eight and transplanting cancer into several more… All physicians take delight in the abuse and torture of the unfortunate

subjects.” A man that seems to be hell-bent on killing Puerto Rico through a cancer infestation would

not seem a suitable candidate to be elected by the US to be in charge of chemical warfare projects and receive a seat on

the United States Atomic Energy Commission, right?

But that’s exactly what happened. He also became vice-president of the

American Cancer Society. Any shocking documentation that would have happened during his chemical warfare period would probably have been

destroyed by now. 10. Pentagon Treats Black Cancer

Patients with Extreme Radiation They were told they would be receiving treatment,

but they weren’t told it would be the “Pentagon” type of treatment: meaning to study the effects of high

level radiation on the human body. To avoid litigation, forms were signed only with initials so that the patients would have no

way to get back at the government. In a similar case, Dr. Eugene Saenger, funded by the Defense Atomic Support

Agency (fancy name), conducted the same procedure on the same type of patients. The poor, black Americans received

about the same level of radiation as 7500 x-rays to their chest would, which caused intense pain, vomiting and bleeding

from their nose and ears. At least 20 of the subjects died. 11.

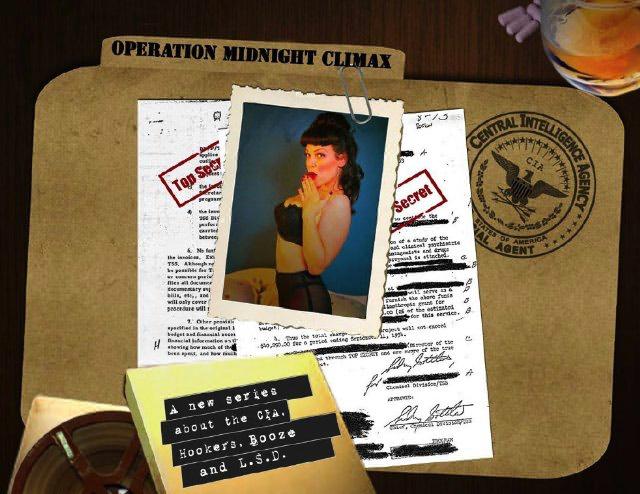

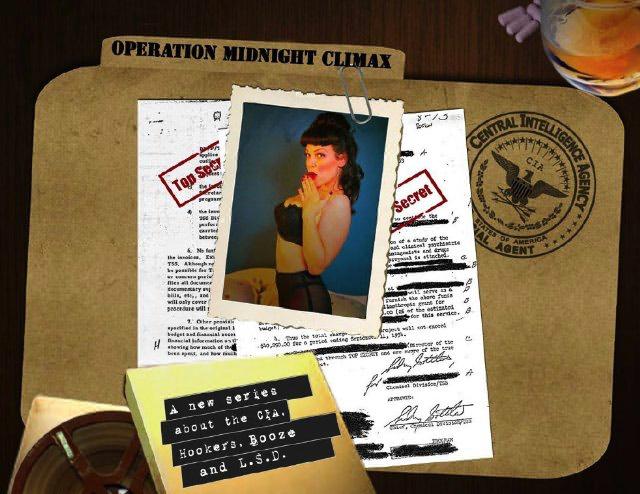

Operation Midnight Climax

Here’s a government experiment

that, when you Google it, has completely different image results than web results. Operation Midnight Climax involved safe houses in New York and San Francisco, built for the sole purpose to study LSD effects on non-consenting individuals.

But in order to lure the individuals there, the CIA made these safe houses out to be, wait for it, Brothels. Prostitutes on the CIA payroll (yes, there was such a thing) lured

“clients” back the houses. Instead of having sex with them, though, they dosed them with a number of substances, most

famously LSD. This also involved extensive use of marijuana. The experiments were monitored behind a two-way mirror, kind of like

a sick, twisted peep show. Furthermore, it’s alleged that the officials who ran the experiments described them as … “it

was fun, fun, fun. Where else could a red-blooded American boy lie, kill, cheat, steal, rape and pillage with the sanction

and bidding of the All-highest?” The most horrifying part was the idea of dosing non-consenting adults with drugs they couldn’t

possibly know the effects of. [The video featuring a soldier talking about Operation Midnight Climax and his experiences with the CIA and the U.S. Government

has been removed from YouTube and the account assocaited with it terminated “due to multiple third party notifications

of copyright infrigement” from claimants including (surprise!) JEWISH COMPANY Philip Morris International.] 12. Fallout Radiation on Unsuspecting Pacific Territories

After unleashing hell upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States embarked

on numerous thermonuclear bomb tests in the Pacific in response to increased Soviet bomb activity. They were intended to be a secret affair. However,

this secrecy would fail. Detonated in 1954 over Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, Castle Bravo was the most powerful nuclear device the US ever set off. What they didn’t expect was for the fallout from the blast

to inadvertently be blown upwind onto nearby residents of other islands. The suffering included birth defects and radiation

sickness. The

effects were greater felt in later years when many children whose parents were exposed to the fallout developed thyroid cancer

and neoplasms. This created Project 4.1, a study to examine the effects of radiation fallout on human beings. Essentially, it was the latest in a long string of

studies where humans act as guinea pigs without giving consent and a project remembered by the US as a way to gather data

that would otherwise be unobtainable. The US moral standard that history best remembers is that even though the radiation fallout

on the people of the Marshall Islands was an accident, it might as well have been intended. In addition, perhaps as nature’s way of

adding insult to injury, a Japanese fishing boat was caught in the fallout. The fishermen all fell ill and one died, making

the Japanese livid that the US was still affecting them with nuclear devices. 13.

Tuskegee, Alabama

The recent uncovering of the US exposing Guatemalans to syphilis brings back to

mind this infamous study. In between 1932 and 1972, researchers recruited 400 black share-croppers in Tuskegee, Alabama to study the natural progression of syphilis. But

the scientists never told the men they had syphilis. Instead, they went around believing that they were being treated for

“bad blood” disease as researchers used them to find out the extent of syphilis symptoms and effects. In 1947, penicillin

became the standard cure for syphilis. But along with withholding information about the disease, scientists also “forgot”

to tell their subjects that what they were being treated for had a cure. And so the study continued for nearly 30 years

more. Once

it was discovered, the backlash to the study was so fierce that President Bill Clinton made formal apology,

stating he was sorry that the government “orchestrated a study that was so racist”. Sadly enough, it

would be horrific, but one of the more docile evil human experiments ever conducted by the U.S. Government. The

Edgewood Arsenal Drug Experiments  The paranoia of the Cold War inspired the military to attempt some highly

dubious experiments, but few compare to their nearly 20-year-long dalliance with illicit substances. Beginning in the 1950s,

Maryland’s Edgewood Arsenal was home to a classified Army research program on psychoactive drugs and other chemical

agents. More than 5,000 soldiers served as guinea pigs for the project, which was intended to identify non-lethal incapacitating

agents for use in combat and interrogations. Unsuspecting Army grunts were given everything from marijuana and PCP to mescaline,

LSD and a delirium-inducing chemical called BZ. Some were even dosed with potentially lethal nerve agents such as sarin and

VX. While the tests produced reams of documentation on the effects of the substances, they discovered no wonder drugs and

created very little practicable intelligence. Many of the subjects, meanwhile, were left with psychological trauma and lingering

health problems. Following a public outcry and a Congressional hearing, the drug experiments were terminated in 1975.

______________________________________________-- Innocent in Dachau: The Trial and Punishment of Franz

Kofler et al. Joseph Halow An unusual set of circumstances, over which I had only limited control,

and timing, over which I had no control whatsoever, determined the course of my military career and led me to work as a court

reporter at Dachau for the 7708 War Crimes Group in Germany after my discharge from the Army. Arriving in Germany innocent

of war and politics, I found my preconceptions of right and wrong during wartime, as well as the justice of the postwar

trials, challenged by what I observed and experienced during the Dachau trials. Many years later, my review of the records

of those trials has only strengthened my belief that justice was not served at Dachau after the war.

* * * * * The war

with Japan ended on August 15, 1945, and I reached the age of eighteen on August 20, 1945. Unhappy with my life in a small

city in Pennsylvania and sure I would in any event soon be drafted into the army, when I registered for the draft on my

eighteenth birthday I asked for immediate induction. I could not have enlisted, since this would have required parental

permission, and the death of my eldest brother in Italy during the war against Germany had so profoundly affected my parents

they would not have considered granting it. My mother, grief-stricken, could only proclaim that had George enlisted and not

been drafted she would have felt she had sent him to his death. The Army moved as rapidly on my request for immediate induction as a Federal bureaucracy is

able. In this case it wasn't until October 23, 1945 before I was taken into the Army. This worked in my favor, for by fall

the nation had such a backlog of servicemen awaiting discharge that thousands of men remained on terminal leave for weeks

until the military service groups were able to process them. I learned of the Army's desperate manpower situation within a few short days of my induction.

At Fort Meade, Maryland, where each day thousands were being separated from the service, anyone with any office training

whatsoever was immediately pulled from the ranks of the other recruits and put to work in Army Administration. The plan was

to send these new recruits to basic training camps later, after the Army had been able to effect the discharge processing

of so many World War II veterans. I

had grown up in Pennsylvania during the Great Depression, and, because of my father's heart condition, which would not permit

him to work, we were probably even poorer than many of our neighbors. It never occurred to me that I would ever attend a

university. I elected to pursue a commercial course in high school, so that I could have a well-paying job as soon as I

graduated and I could begin a business career. Excelling in my studies, I broke the high school speed record in shorthand

by passing a speed test at 175 words per minute. This ability determined the course of my military service for the next two and a half years. I was not sent to a

basic training camp but instead was put to work in G-4, the administrative office at Fort Meade. Hopelessly lost at a desk

at which I was expected to work independently -- for I had no experience and I received virtually no guidance whatever --

I was pleased when, after only two or three weeks, I was asked to serve as a reporter on Army Retiring Board cases. The work

was much easier than office administration, in which I was charged with responding to correspondence which I was unable

to understand. Reporting required no experience, although attempting to record the proceedings faithfully is obviously stressful.

This assignment lasted less than two months, for on my return to base from a Christmas furlough I learned that I was one

of two enlisted men selected to go to China. Chosen on the spur of the moment, we flew to China in propeller planes, and even under the A-1 priority assigned

our travel, it was a week before we arrived in the city now called Beijing. We learned that our mission was to establish

offices which would administer the negotiations the United States was then mediating between the Communists and the Nationalists.

Today it is difficult for me to imagine the extent of my political naiveté during the time I was stationed in China.

The intent of our mission there I found incomprehensible. It may have been because we were an immigrant family, but at home

in Pennsylvania, before I entered the Army, I was not at all interested in even American politics. At that time I could

not have distinguished between the Republicans and the Democrats. In China, although I worked in the Commanding General's

office and had access to every bit of information available, no matter how highly classified it was, I failed to understand

the differences between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists. It seemed obvious to me then that we favored the Nationalists,

but it was not until much later that I understood the reasons for establishing the Peiping Headquarters Group, as our outfit

was named. When I arrived in

China I had been in the Army exactly two and a half months, and I was still completely lost in an office. Thanks to my buddy

Smitty's administrative abilities and his experience, we soon earned a good reputation and were highly regarded by officers

and the enlisted men alike. My

tour in China ended on the termination of the six-month period of temporary duty. Although Smitty and I could have stayed

on, both of us elected to return. We were ordered to Washington, D.C., and there assigned to the Office of the Chief of

Staff, Europeari Division, at the Pentagon. After months of bored inactivity at the Pentagon, I was discharged from the Army on December 2, 1946. I longed to

see more of the world, and sought a job with the Department of the Army abroad. Since I was still only nineteen, however,

I was considered to be too young for overseas employment as a civilian. I argued that I had been overseas in the Army, where

I had to manage essentially alone. The Civilian Personnel office agreed (probably because of the shortage of shorthand reporters

in the European Theater). Despite my trepidation about being assigned to Germany, I left New York on the S.S. Marine

Angel on December 10, 1946, and arrived in Bremerhaven, Germany, on December 21st. From there I traveled to Augsburg,

where I awaited assignment as a pre-trial reporter on a war-crimes investigating detachment. There were at least fourteen

such detachments, and each of them was to assign its own pre-trial reporter. The first few months I spent in Germany were particularly unpleasant, due

to an unusually severe winter and a shortage of fuel. We Americans had to cut back on our use of heating fuel, and so we

were constantly cold, inside as well as outside our quarters. If our fuel rations were limited, rations for the Germans

simply did not exist, and I later learned that they would frequently awaken to find frost on their inside walls, which remained

frigid all day. When the pre-trial

detachments had finished their work, I was transferred to Dachau, to serve as an official reporter in the American trials

at Dachau. The German cities I had seen had been so thoroughly destroyed by Allied bombers that it was a pleasure for me

to come to Dachau. There, although one could purchase nothing in any of the shops, the buildings were at least intact. The

summer of 1947, following the extremely cold winter, was also unusually warm and sunny, with mild weather which lasted through

the fall. This made living conditions in Dachau very pleasant for me, though this contrasted starkly with the gloom involved

in the cases we tried in court. *

* * * * So many years have passed since the war crimes trials

that I should perhaps explain that my unit, the 7708 War Crimes Group, was assigned the function of administering and holding

the war crimes trials which took place under the aegis of the American military government in Dachau, Germany. This included

trials of cases involving concentration camps in Germany and Austria, as well as trials of isolated atrocity cases. The

latter involved the fates of crews from American planes shot down during bombing raids over Germany. Fliers forced to parachute

from their disabled planes were often attacked by civilians from the towns in which these bombing raids had taken place.

The enraged German civilians would then kill the unfortunate fliers, either by beating to death or shooting them, sometimes

both. It was on one of these

atrocity cases that I was tested for my ability to report officially. Working with an experienced official reporter, I was

to sit through the trial in order to understand and learn the procedure. I then had to record and transcribe the proceedings

of one official court session or "take," a period of approximately one and a half hours in court. Had I failed

the test, I would doubtless have been transferred to some other function. I did pass the test, which proved to be more trying

to my emotions than to my skill as a reporter. I might have been indifferent regarding this trial had it not been for a young "accused" (as we called

the defendants), who sat in the dock with several other, appreciably older, German civilians. He was so much younger than

the others that I took note of him as soon as I entered the courtroom. I watched him throughout, and, undoubtedly because

he sensed I was his peer, he watched me. Checking the record, I learned that the defendant, Rudolf Merkel, was six months

younger than I; I was still only nineteen. The crime for which he was being tried had taken place when he was fifteen, when

the other accused had attacked a flier who had parachuted into an area close to his town. Two of the older men had struck

the flier, and on their instruction, Merkel had struck him twice with a stick. My excitement during the proceedings had grown to a fever pitch by the

time the court announced its sentences. When young Rudolf Merkel was sentenced to life imprisonment I was stunned. On hearing

his sentence, young Merkel broke down. Tears streamed down his face, and he shook as he fought back the sobs which tore

through his body. Throughout the trial I had sympathized with the murdered flier, my countryman, and had been deeply shaken

to hear of his pathetic attempts to escape the attacks of the infuriated German townspeople. Now I was struck by the plight

of this boy, and I had to look away to avoid crying with him. Listening to the testimony, I had already concluded that in

his shoes I would have acted, despite my peaceful nature, as he had. Going a step further, I soon realized that had this

happened in America those who had disposed of an enemy flier would have been considered heroes. We, the victors, considered

them lawless criminals. I came to the conclusion that in such cases it is invariably the winners who determine whether those

involved are heroes or terrorists. After

I had transcribed this testimony, I was told I had passed the test. My response was to say that I did not feel I was emotionally

able to work in court. After three days, however, I realized that I had very little choice. I was under contract with the

7708 War Crimes Group as a reporter (technically a pre-trial reporter). To the best of my knowledge, there was no other

position available to me. I returned to work, where, after my baptism of fire, I soon adjusted. I could listen to the sentences