Early life

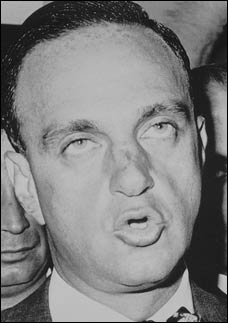

Joseph McCarthy was born to a poor Irish Catholic farm family in

Appleton, Wisconsin.

A hyperactive, extroverted youth, he dropped out of school

after eighth grade to start

his own poultry business. After the chickens all

died, he enrolled in the local public high

school. Thanks to enormous energy

and a retentive mind, he finished his coursework

in less than a year at age 20.

After two undergraduate years at Marquette University, a

leading Jesuit school in Milwaukee, McCarthy entered Marquette Law School, acquiring

the rudiments of the profession

that he soon used to knit together a statewide network

among Irish and German

Catholics. McCarthy was a practicing Catholic his entire life,

but rarely referred

to religion or ethnicity in his speeches. He actively supported President

Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Young Democrats, but did not join Irish organizations.

Although defeated in his 1936 race for district attorney, McCarthy displayed remarkable

campaign abilities and an astonishing memory for faces. He had the energy and determination

to meet every voter in person, exuding charm and a concern for the voter as an individual.

The same tactics paid off in 1939, when he was successful in a nonpartisan contest

for a regional judgeship.

The youngest

judge in state history, he worked long hours to clear up a large backlog.

He

administered justice promptly and with a combination of legal knowledge and good

sense.

He was still a Democrat, but that party was very weak statewide at the time.

Military service

In 1942 McCarthy,

volunteered for the Marines (as a judge he was draft exempt), becoming

an intelligence officer in an aviation

unit heavily engaged in combat in the South Pacific.

Although assigned a desk

job McCarthy flew numerous combat missions as a tail gunner

—he exaggerated

the number to qualify for a Distinguished Flying Cross.

During

his 30 months of military service, McCarthy's record was unanimously praised by

his commanding officers and Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific

Fleet. Admiral Nimitz issued the following

citation regarding the service of Captain McCarthy:

| “ | For meritorious and efficient performance of duty as an observer and rear gunner

of a dive bomber attached to a Marine scout bombing squadron operating in the Solomon Islands area from September 1 to December 31, 1943. He participated in a large number of combat missions,

and in addition to his regular duties, acted as aerial photographer. He obtained excellent photographs

of enemy gun positions, despite intense anti-aircraft fire, thereby gaining valuable information

which contributed materially to the success of subsequent strikes in the area. Although suffering from a severe leg injury, he refused to be hospitalized and continued to

carry out his duties as Intelligence Officer in a highly efficient manner. His courageous devotion

to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service. | ” |

Elected to Senate, 1946

McCarthy had his name entered in the Republican

primary for U.S. Senate in 1944,

opposing a well-entrenched incumbent Republican,

Alexander Wiley. The absentee

war hero ran a strong second, making a name for

himself statewide and making himself

available for the 1946 Senate contest.

Why McCarthy suddenly changed parties was never explained, but

prospects for ambitious

Wisconsin politicians were dim inside the poorly organized

Democratic party, for most

New Dealers supported the state’s Progressive party. During the war, however, that

party collapsed, torn apart between its New Deal domestic liberalism, and its intensely

isolationist opposition to Roosevelt’s

foreign policy. Increasingly out of touch with

Wisconsin, its leader Robert LaFollette Jr. looked to his family’s past glories and

made the blunder of trying for

reelection to the Senate in 1946 as a Republican.

"Tail

Gunner Joe," as his posters called him, endlessly crisscrossed Wisconsin while

LaFollette

remained in Washington, offered an alternative in the Republican primary

to old

guard Republicans who had opposed the Lafollettes for a half century. McCarthy

brilliantly

captured the frustrations citizens felt about massive strikes, unstable economy,

price controls, severe shortages of housing and meat, and the growing threat of from the

far left in the CIO. He nipped LaFollette in the primary. The slogan “Had Enough?—Vote

Republican” gave the Republicans a landslide all across the North, electing a new

junior senator from Wisconsin.

Communist Issue

In Washington, McCarthy was a mainstream conservative

in domestic policy, and, like

many veterans, was an internationalist in foreign

affairs, supporting the Marshall Plan

and NATO. His speeches rarely mentioned domestic Communism or flaming issues

like the

Alger Hiss espionage case, but that suddenly changed in early 1950 when his

vivid anti-Communist rhetoric drew national attention. "The issue between the Republicans

and

Democrats is clearly drawn. It has been deliberately drawn by those who have

been in charge of twenty years of treason.” Alleging there were many card-carrying

Communists in U. S. President Harry S. Truman’s State Department, McCarthy forced

a Senate investigation led by Millard

Tydings, Democrat of Maryland. McCarthy named

numerous suspect diplomats but failed to convince the three

Democrats on the panel;

they concluded his allegations were “a fraud and

a hoax,” while the two Republicans

dissented. McCarthy retaliated by campaigning

against Tydings, who was defeated for

reelection in November 1950. What the

senator himself called McCarthyism was a factor

in key races across the country;

all his candidates won and his stock soared. A few

weeks later American forces

were crushed by the Chinese in Korea, and in spring

1951 Truman tried to shift the blame by firing General Douglas MacArthur.

Support from Catholics and Kennedys

The great majority of Catholics were anti-Communist, but they were

also loyal Democrats,

so to enlarge his base McCarthy, a Republican, needed

an alliance with anti-Communist

Catholics. The Catholic bishops and the Catholic

press was "among McCarthy's most

fervid supporters." A major connection

was with the powerful Kennedy family, which had

very high visibility among all

Catholics in the Northeast.[7] Well before he became famous

McCarthy became closely associated with Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr.. He was a frequent

guest at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port and at one

point dated Joe's daughter

Patricia. After McCarthy became nationally prominent,

Kennedy was a vocal supporter

and helped build McCarthy's popularity among Catholics.

Kennedy contributed cash and

encouraged his friends to give money. Some historians

have argued that in the Senate

race of 1952, Joe Kennedy and McCarthy made a

deal that McCarthy would not

make campaign speeches for the Republican ticket

in Massachusetts, and in return,

Congressman and future U.S. President John F. Kennedy would not give anti-McCarthy

speeches. In 1953 McCarthy hired Robert Kennedy as a senior staff member. When the

Senate voted to censure McCarthy in 1954,

Senator Kennedy was in the hospital and never

indicated then or later how he

would vote; he told associates he could not vote against

McCarthy because of

the family ties.

Political dominance

In 1950, McCarthy discussed his upcoming 1952 campaign with three

fellow Catholics

(Father Edmund A. Walsh and Charles H. Kraus of Georgetown University and Washington

attorney Wiliam A. Roberts). Kraus had recommended Father

Walsh's recent books

dealing with Communism to McCarthy, and was hoping to interest

McCarthy in the problems

of Communism in the world. McCarthy's reputation among

the voters was not good at

that time, due to various ethical and tax violation

problems, and he needed an issue that

would help improve his chances of re-election.

He latched enthusiastically onto the idea

of attacking Communists in the government.

Subsequently, McCarthy called Willard Edwards of the Chicago Tribune asking for assistance

with a speech on Communism. Edwards sent some materials,

including a copy of a letter

written on July 26, 1946, by James F. Byrnes, Secretary of State under Truman. This

letter was the central support for

McCarthy's subsequent claims to have a list of

Communists in the government.

- "Pursuant

to Executive Order, approximately 4,000 employees have been transferred...

- Of those 4,000

employees, the case histories of approximately 3,000 have been

- subjected to a preliminary

examination, as a result of which a recommendation against

- permanent employment has been

made in 284 cases by the screening committee...

- Of the 79 actually separated from the service,

26 were aliens and therefore under

- "political disability" with respect to employment

in the peacetime operations of the

- Department. I assume that factor alone could be considered

the principal basis

- for their separation."

This document was repeatedly cited by McCarthy as the basis for

his accusations; unfortunately, there was no list at that time.

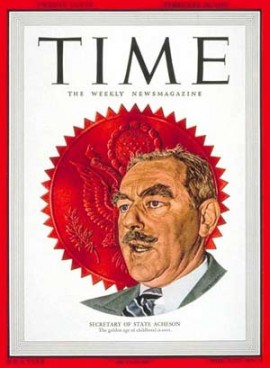

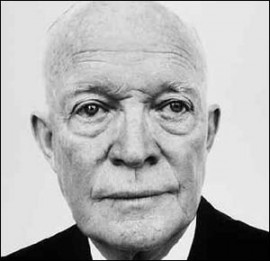

McCarthy now became one of the dominant leaders in American politics, with strong

support among both Republicans and Catholic Democrats, as he alleged that Truman’s

top people had betrayed America. He singled out Secretary of State Dean Acheson and

Secretary of Defense George Marshall. Liberals were aghast; Truman had picked General

Marshall to head the State

and Defense departments precisely because he thought the

elderly statesman would

always be above criticism, no matter that China turned from a

staunch ally to

a bitter enemy on his watch. McCarthy’s blistering attacks on Marshall as

“part of a conspiracy so immense, an infamy so black, as to dwarf any in the history of

man” fueled the belief he was a wild-man, a pathological liar who overstepped the

bounds of political discourse.

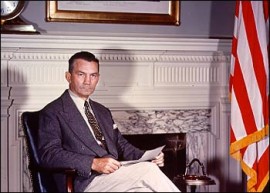

With Dwight D. Eisenhower crusading against “Korea, Communism and Corruption” in

1952, Republican

victory was assured. As a senior member of the majority party McCarthy

for

the first time became a committee chairman, with control of staffing and agenda. He

used

his Government Operations Committee to open highly publicized hearings in

1953-54

alleging disloyalty in the State Department, the United States Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA), the U.S. Information Agency, and finally the Army. His furious attacks

on the Army

led to the televised “Army-McCarthy” hearings in spring

1954, which exposed his bullying

tactics to a national audience. As McCarthy’s

poll rating plunged, his enemies finally

pulled together to introduce a censure

resolution focused on charging McCarthy

with contempt for the federal government,

and especially for his fellow senators.

Backlash

McCarthy’s charges that over-educated liberals

tolerated Communism at home and abroad

had stung the liberals. He alleged that

they had corruptly sold out the national interest

to protect their upper class

privileges, and were so idealistic about world affairs that

they radically underestimated

the threat posed by Soviet dictator Stalin, his spies, and

the worldwide Communist movement. Instead of refuting the

allegations, Liberals tried

one of two approaches. Some became intensely anti-Communist

and claimed they were

more effective than McCarthy and the Republicans in eliminating

Communism in the

unions and Democratic party, and in containing the Stalinist

menace in Europe. The other

approach was to counterattack, to charge that “McCarthyism”

never found a single spy

but hurt innocent people in hunting for nonexistent

witches; thus it represented an evil

betrayal of American values. In an appeal

to upscale conservatives and liberal intellectuals,

critics ignored the Communist

infiltration of labor unions and liberal causes and focused

on stereotyping anticommunists

as ill-mannered ignorant troglodytes, oblivious to American

traditions of free

speech and free association. McCarthy’s exaggerations and false charges

encouraged opponents to stress the second approach, but it escalated the controversy

to a pitch of hatreds and fears unprecedented since the days of Reconstruction.

Loss of influence

McCarthy’s superb sense of timing and his media instincts kept his partisan

attacks

on the front page every day; his willingness to do battle in the hustings

with Democratic

opponents across the country strengthened his base in the Republican

party. His

religion and ethnicity, refreshed with highly visible friendships

with leading Irish Catholics,

especially the Kennedy family, bolstered his standing

among Democrats. According to

Gallup, McCarthy’s popularity crested in

January 1954, when he was endorsed by all

voters 50-29 (with 21 having no opinion).

His core support came from Republicans and

Catholics who had not attended college.

McCarthy, however, failed to create any sort of grass

roots organization. He had no

organizational skills; he did not effectively

use his talented staffers (such as Robert Kennedy).

He was a loner who lurched from issue to issue, misled by the enormous media

publicity

into believing that a one-man crusade was possible in an increasingly

well-educated

complex society honeycombed with local, regional and national organizations.

By operating

within the Republican party apparatus he lost the opportunity to

create an independent grass

roots political crusade in the style of Teddy Roosevelt, Huey Long, or Ross Perot. He

never launched his own magazine or radio show or formed alliances with publishers

who agreed with him.

McCarthy’s

strained relations with Senate colleagues created a trapdoor. It was sprung

after

many Republicans realized that he had shifted the attack away from the Democrats.

What use was his slogan “20 Years of Treason” once Eisenhower was in office? McCarthy’s

answer was “21 Years of Treason!” Eisenhower’s supporters could no longer tolerate such

a loose cannon, and as McCarthy unwisely shifted his attacks to Eisenhower’s beloved

Army,

his cause was doomed. While many Americans distrusted Ivy League, striped pants diplomats,

soldiers were held in high regard; McCarthy’s

charges of subversion were flimsy (one Communist

dentist had been automatically

promoted); he sabotaged his own reputation by finagling favors

for an aide who

had been drafted. The televised hearings proved fatal to an ill-prepared bully.

After the Democrats regained control of Congress in the 1954 elections, the censure motion

carried, 67-22. McCarthy’s appeal, so widespread yet superficial,

evaporated

overnight and the Senator faded into the shadows.

The term "McCarthyism"

McCarthy is permanently associated with the use of the word "McCarthyism" (a word which

he did not coin, but of which he did make use according to a sense more aligned with his

actual philosophy) to mean an aggressive attack on Communists who had infiltrated America

and on the liberals who protected them—an attack, however, without regard for due

process. Although the left was unable to make heroes of the people who supported and

sometimes were controlled by Stalin, they did make heroes of opponents of McCarthy,

painting him as the internal menace to American values that was far worse than

Communist subversion. Schrecker (1998) sees McCarthyism as anti-Communist political

repression of the early Cold War, and explores its mechanisms through, and what she

considers the exaggerated public fears on which it depended. During the 1940s-1950s,

McCarthyism took on a variety of forms with an array of agendas, interested parties,

and modes of operating. Despite its widespread and popular character, it started with

the federal government and was driven by a network of dedicated anti-Communist

crusaders such as J. Edgar Hoover, director of the United States Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI). McCarthyism's repression both responded to and

helped create widespread

fears of a significant threat to national security.

Margaret Chase Smith, Republican senator from Maine, gained a national reputation as

one of the earliest critics McCarthyism with

a Senate speech on June 1, 1950, called

"the Declaration of Conscience."

It was an attempt by Smith to address the excesses of

McCarthyism, and was widely

hailed as a call to reason by McCarthy's opponents. Smith

gave a critique of

the American political process and political institutions in the responses

to

dissent on the left and the right. Smith, like other McCarthy critics, sought to bring a

level of civility to political protest and dissent. She and many others who objected to

the tactics of McCarthy actually believed in the underlying tenets of his anti-Communist

crusade. Their responses to his excesses reflected a desire to narrow the scope

of acceptable political dissent.

Impact on government

Rausch (2000) argues McCarthy's campaign

| “ | had a lasting impact on the conduct of U.S. foreign relations, particularly among professional diplomatic institutions like the State Department and its Foreign Service personnel, and McCarthyism did not disappear with the senator's censure in

1954. The 'ism' in a broad sense was a set of ideas not only about internal subversion

but also about the outside world, including a simplistic, isolationist anti-communism

and a deep suspicion about social reform movements abroad. It stood in open opposition to a more complex, even accommodating, view of communism. Instead of ending the hunt for subversives begun under Truman, Eisenhower made the search systematic, universal, and more broadly defined. McCarthyist Scott McLeod took over security and personnel functions of the State Department and became one of the most famous and despised men in the executive branch. McLeod brought McCarthyist

methods and assumptions to bear in ridding the department of what he defined as

security risks. Oral history sources provide key evidence for the destructive atmosphere

within the department in these years, and they shed valuable light on McLeod's

impact on the foreign affairs bureaucracy. In the short term, the Foreign Service

declined in morale, prestige, and influence. By 1954, professionally trained diplomacy,

with nuanced, internationalist views lost ground to more simplistic, strictly anticommunist

views. During Eisenhower's second term, the Foreign Service and the more moderate

approach experienced a resurgence but still faced opposition from hard-liners

who survived the McCarthy years. The Latin American branch of the department

embodied the changes in professional diplomacy towards one region of the world.

Within the division were the institutionalized tensions of the Eisenhower administration, between career diplomats and political appointees, conservative and moderate anti-communists, and trained diplomats and other specialists. The U.S. embassy in Cuba showed this internal conflict in a microcosm, as the administration's response to Latin American revolution evolved after 1954. McCarthyism accompanied Eisenhower into office, and its effects continued into his last foreign policy crisis and beyond." | ” |

In California McCarthyism began before the Senator was famous. In 1946 in the Los Angeles

schools two teachers from Canoga Park High School were called before the Tenney

Senate

Investigating Committee on charges of communistic teaching. The two teachers

were exonerated of all charges, but a campaign to rid the LA district of dissident teachers

was effectively launched. The target of the campaign was a group of teachers who belonged

to the Los Angeles Federation of Teachers (LAFT), formerly known as Union Local 430

and chartered under the American Federation of Teachers, until 1948, when the AFT revoked

the charter. By 1954, Los Angeles teachers were required to take five loyalty oaths, although

not one teacher was ever charged with or convicted of subversion. In 1953, the Los Angeles

City School Board announced that 304 teachers were to be investigated because of alleged

Communist affiliations. The Dilworth Oath, made law in 1953, required teachers to answer

questions posed to them by the Investigating Committees. Teachers who refused to answer

the Committee questions by claiming their Fifth Amendment rights could then be fired by

the Board for insubordination.

Media and popular

culture

Historians have debated the degree to which McCarthyism permeated the American

mood and popular culture. Anti-Communist liberals at the time said it played to isolationism

(especially strong in McCarthy's Wisconsin) by diverting attention away from the real

threat, Stalin's Soviet Union as an external power. The Left said that they had a First

Amendment right to their beliefs and that McCarthyism had a chilling effect. Dussere

(2003) shows that comic strip artist Walt Kelly in "Pogo" parodied McCarthyism and promoted

leftist politics as old-fashioned American common sense, representing a time when

concerns about art and politics with respect to popular culture were in the forefront.

Hoover's FBI targeted retired film comedian Charlie Chaplin because of his status as a

cultural icon and as part of its broader investigation

of Hollywood. Some of Chaplin's films

were considered "Communist propaganda,"

but because Chaplin was a British citizen and

was not a member of the Communist

Party, he was not among those investigated by the

House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. Nevertheless, he was vulnerable to

protests by the American Legion

and other patriotic groups because of both his sexual and

political unorthodoxy.

Although countersubversives succeeded in driving Chaplin out of the

U.S., they

failed to build a consensus that Chaplin was a threat to the nation. Chaplin's story

testifies to both the power of the countersubversive campaign at mid-century and to some

of its limitations.

Strout (1999) looks at

The Christian Science Monitor during the McCarthy era (1950-1954);

it was a highly influential newspaper at

home and abroad. Strout asks: (1) Was the Monitor

a consistent critic

of McCarthy? (2) How did the coverage compare to other elite and popular

press

newspapers? (3) How did the pressures associated with McCarthyism effect individuals

at the Monitor and its news product? An extensive review of editorials and news articles

suggests that it was thorough and fair in reporting, yet outspoken and responsible in

editorial criticism. Mary Baker Eddy's original 1907 statement that, "The purpose of

the Monitor is

to injure no man, but to bless all mankind," was referred to repeatedly in

interoffice correspondence during the McCarthy era. The Monitor did not attack McCarthy

personally as other papers did; rather, its criticism centered on the actions of the senator

and the negative effects they were having at home and abroad. The Monitor served as

a voice of moderation, yet at the same time, remained a persistent critic of McCarthy's tactics.

Individuals were affected by the pressures of McCarthyism. For instance, veteran Washington

correspondent Richard L. Strout was suspended from covering McCarthy for eight to 12

months after being mentioned in McCarthy's book, McCarthyism: The Fight for America.

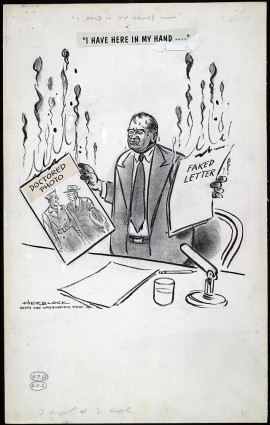

I have in my hand...

FBI Master Chart of distribution in 1945-46 of investigative reports to the White House, Attorney General, and

employing agencies of Communist agents in the Federal government.

It

was McCarthy's charges of Communist, security, and loyalty risk infiltration of the

State

Department that shot him into prominence in 1950. At a Lincoln Day speech, on

February

9, 1950, before the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia,

at the Colonnade Room of Wheeling's McClure Hotel, he stated:

| “ | I

have in my hand 57 cases of individuals who would appear to be either card-carrying

members or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still

helping to shape our foreign policy. | ” |

McCarthy compiled a list of 57 security risks and publicly named John S. Service, Gustavo

Duran, Mary Jane Keeney, Harlow Shapley, and H. Julian Wadleigh as being on the list.

These names came from the "Lee List"

of unresolved State Department security cases

compiled by the earlier investigators

for the House Appropriation Committee in 1947.

Robert E. Lee was the committee’s

lead investigator and supervised preparation of the list.

In

a six-hour speech on the Senate floor on February 20, 1950 in which McCarthy was

constantly interrupted by hostile senators; four of whom — Scott Lucas (61 times),

Brien McMahon (27 times), Garrett Withers (22 times), and Herbert Lehman (13 times)

— interrupted him a total of 123 times, McCarthy raised the issue of some eighty individuals

who had worked in the State Department, or wartime agencies such as the

Office of War Information (OWI) and the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW).

McCarthy sought

to avoid naming names publicly when possible, using numbered cases

instead of

names in public session. He preferred to name his suspects only in executive

session, in order to protect those who might have been erroneously identified by the

FBI,

State Department Security, Army counterintelligence, etc. "[I]t would be improper

to make the names public until the appropriate Senate committee can meet in executive

session and get them," explained McCarthy. "If we should label one man a Communist

when he is not a Communist I think it would be too bad."

But when McCarthy began reading his numbered cases to the Senate, the Democrat

Majority Leader, Illinois Senator Scott Lucas, interrupted, "I want him to name those

Communists."

In response to McCarthy's desire not to name names publicly in order to

protect

the innocent, Lucas bizarrely referred to the fact that statements in Congress are

privileged

against defamation suits, saying, "if those people are not Communists the senator

will be protected." (This was hardly germane: McCarthy's expressed concern was not

about protecting himself, but protecting suspects who might be innocent.) McCarthy responded:

| “ | The

Senator from Illinois demanded, loudly, that I furnish all the names. I told him at that

time that so far as I was concerned, I thought that would be improper; that I

did not have all the information about these individuals ... I have enough to convince me that either they are members of the Communist Party or they have given great aid to the Communists: I may be wrong. That is why I said that unless the Senate demanded that I do so, I would not submit this publicly, but I would submit it to any committee — and would let the committee go over these in executive session. It is possible that some of these persons will get a clean bill of health... | ” |

Democratic Senator William Benton of Connecticut introduced a bill to eject McCarthy

from the Senate. His first charge was that

at Wheeling, McCarthy had said that he had

a list of 205 names, rather than 57

names. The Senate (then under Democrat control)

sent staff investigators to Wheeling

to try to substantiate Benton's charges. The

investigation found no evidence

to support Benton's charge. According to one investigator:

| “ | The newly unearthed evidence demolished Senator Benton’s

charges in all their material respects and thoroughly proved Senator McCarthy’s

account of the facts to be truthful. | ”

|

Senate

Democrats quietly buried the 44-page staff memo summarizing these findings, but

the

charge that McCarthy had said “205” was likewise dropped. Thus the Congressional

Record to this day records that McCarthy said "57," not "205." Nevertheless, many

on

the left continue to promote Benton's discredited claim as gospel. Benton

made this allegation

only about McCarthy's speech in Wheeling, West Virginia

and not in the other cities where

he made the speech. The 205 number actually

came in another part of his speech; on

February 20, 1950, in a speech made on

the floor of the Senate, McCarthy officially

clarified the issue:

| “ | I have before me a letter which was reproduced in the Congressional Record on August 1, 1946, at page A4892. It is a letter from James F. Byrnes, former Secretary of State. It deals with the screening of the first group, of about 3,000. There were a great number of subsequent screenings. This was the beginning. The letter deals with the first group of 3,000 which was screened. The President— and I think wisely so—set up a board to screen the employees who were coming to the State Department from the various war agencies of the War Department. There

were thousands of unusual characters in some of those war agencies. Former Secretary

Byrnes in his letter, which is reproduced in the Congressional Record, says this: Pursuant to Executive order, approximately 4,000 employees have been transferred to the Department of State from various war agencies such as the OSS [Office of Strategic Services], FEA [Foreign Economic Administration], OWI [Office of War Information], OIAA [Office of Inter-American Affairs], and so forth. Of these 4,000

employees, the case histories of approximately 3,000 have been subjected to a

preliminary examination, as a result of which a recommendation against permanent

employment has been made in 285 cases by the screening committee to which you

refer in your letter. In other words, former Secretary

Byrnes said that 285 of those men are unsafe risks. He goes on to say that of

this number only 79 have been removed. Of the 57 I mentioned some are from this

group of 205, and some are from subsequent groups which have been screened but

not discharged. I might say in that connection that the investigative agency

of the State Department has done an excellent job. The files show that they

went into great detail in labeling Communists as such. The only trouble is that

after the investigative agency had properly labeled these men as Communists the

State Department refused to discharge them. I shall give detailed cases. | ” |

McCarthy was able to characterize President Truman and the Democratic Party as soft

on or even in league with the Communists. McCarthy's allegations were rejected by Truman

who was unaware of Venona project decrypts which corroborated

Elizabeth Bentley's debriefing after her defection from the Communists.

According

to Gallup, McCarthy’s popularity crested in January 1954, when he was

endorsed

by all voters 50-29 (with 21 having no opinion). His core support came from

Republicans and Catholics who had not attended college. On March 9, 1954, CBS

broadcasted Edward R. Murrow's See It Now TV documentary attacking McCarthy.

Venona files

In 1995, when the Venona transcripts were declassified, further detailed information was

revealed about

Soviet espionage in the United States. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover

was among only a handful of people in the U.S. Government who was aware of

the

Venona project, and there is no indication whatsoever Hoover shared Venona

information

with McCarthy. In fact, Hoover may have actually fed McCarthy disinformation, or dead

end files, in an effort to put pressure on relatives, friends, or

close associates of real

Venona suspects by threatening to reveal embarrassing

information about them in

a public forum if they failed to cooperate and reveal

what they might have known about

someone's else’s activities and associations.

And there is no indication

McCarthy might have known he was being used by Hoover

in this way.

On February 7, 1950, three days before

McCarthy's acclaimed Wheeling, West Virginia

speech, Hoover testified before

House Appropriations Committee that counterespionage

requires "an objective different from the handling of criminal cases.

It is more important

to ascertain his contacts, his objectives, his sources of

information and his methods of

communication" as "arrest and public

disclosure are steps to be taken only as a matter

of last resort." He concluded

that "we can be secure only when we have a full knowledge

of the operations

of an espionage network, because then we are in a position to

render their efforts

ineffective."

McCarthy is said to have made the

claim, "I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list

of names that

were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the

Communist Party."

The famous "List", as it has come to be known, has always engendered

much controversy. The figure of 205 appears to have come from an oral briefing McCarthy

had with Hoover regarding espionage suspects the FBI was then investigating. The FBI

had discovered on its own five Soviet agents operating in the United States during World

War II; defector Elizabeth Bentley further added another 81 known identities of espionage

agents; Venona materials had provided the balance, and by the time a full accounting of

true name identities was compiled in an FBI memo in 1957, one more subject had

been added to the number, now totaling 206.

Much

confusion has always surrounded the subject. While the closely guarded FBI/Venona

information

of identified espionage agents uses the number of 206, McCarthy in his Wheeling

speech only referred to Communist Party membership and other security risks, and not

espionage

activity. Being a security risk as a Communist Party of the United States of America

(CPUSA) member does not necessarily entail or imply that a person was or is

actively involved

in espionage activity. Venona materials indicated a very large

number of espionage agents

remained unidentified by the FBI. When McCarthy was

questioned on the number, he

referred to the Lee List of security risks, by which

it appears Hoover was attempting to

match unidentified code names to known security

risks. Hoover kept the identities of persons

known to be involved in espionage

activity from Venona evidence secret. Hoover in the very

early days of the FBI's

joint investigation with the Army Signals Intelligence Service in May

1946 did precisely the same deception with a confidant of President Truman using Venona

decryptions. Hoover reported that a reliable source revealed

“an enormous Soviet espionage

ring in Washington.” Of some fourteen

names, Soviet agents Alger Hiss and Nathan Gregory

Silvermaster were listed well down the list. The name at the top was “Undersecretary of State

Dean Acheson” and included others beyond reproach, thus discrediting the Hiss and

Silvermaster

accusations, which actually were on target. Hence the Truman White

House always

suspected Hoover and the FBI of playing partisan political games with

accusations

of various administration members’ complicity in Soviet espionage.

The Venona project specifically references at least 349 pseudonyms in the United States

—including citizens, immigrants, and permanent residents—who cooperated in various

ways with Soviet intelligence agencies, however not all were ever identified. In public

hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI) conducted by

McCarthy, 83 persons pled the Fifth Amendment right against

self incrimination. An

additional 9 persons refused to testify on constitutional

grounds in private hearings,

and their names were not made public. Of the 83

persons pleading the Fifth Amendment,

several have been identified by NSA and FBI as agents of the Soviet Union

in the Venona project involved in espionage. Several prominent examples are:

- Mary Jane Keeney, a United Nations employee, and her husband

- Philip Keeney, who worked in the Office of Strategic Services;

- Lauchlin Currie, a special assistant to President Roosevelt;

- Virginius Frank Coe, Director of Division of Monetary Research, U.S. Treasury;

- Technical Secretary at

the Bretton Woods Conference; International Monetary Fund;

- William Ludwig Ullman, delegate to the United Nations Charter Conference and Bretton Woods Conference;

-

Nathan Gregory Silvermaster, Chief Planning Technician, Procurement Division,

Nathan Gregory Silvermaster, Chief Planning Technician, Procurement Division,

- United States Department of the

Treasury and head of the Silvermaster network of spies;

The Silvermaster ring operated primarily in the Department of

the Treasury but also had contacts in the

Army Air Force and in the White House. Sixty-one of the Venona cables concern the activities of the

Silvermaster spy

ring.

Frank Coe, Assistant Director, Division of Monetary Research, Treasury Department; Special Assistant to the United States Ambassador in London; Assistant to the Executive Director, Board of Economic

Warfare; Assistant

Lauchlin Currie, Administrative Assistant to President Roosevelt; Deputy Administrator of Foreign Economic

Administration; Special Representative to China

Senate Subcommittee on War Mobilization; Office of Economic

Programs in Foreign Economic Administration

Sonia Steinman Gold, Division of Monetary Research U.S. Treasury Department; U.S. House of Representatives

Sonia Steinman Gold, Division of Monetary Research U.S. Treasury Department; U.S. House of Representatives

Select Committee on Interstate Migration; U.S. Bureau of Employment Security

Irving Kaplan, Foreign Funds Control and Division of Monetary Research, United States Department of the

Irving Kaplan, Foreign Funds Control and Division of Monetary Research, United States Department of the

William Henry Taylor, Assistant Director of the Middle East Division of Monetary Research, United States Department of Treasury Research, Department of Treasury; Material

and Services Division, Air Corps Headquarters, Pentagon

Harold Glasser, U.S. Treasury Representative to the Allied High Commission in Italy; Robert T. Miller, Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs; Near Eastern

Division

United States Department of State; also identified in the Gorsky Memo

from Soviet Archives; McCarthy's Case #16 and Lee list #12;

of the

Central European Section of Office of Strategic Services; First Chief of Research

Gerald Graze, U.S. State Department; Lee List #29, confirmed in the Gorsky Memo from Soviet Archives, brother of Stanley Graze;

David Karr, Office of War Information; chief aide to journalist Drew Pearson.

David Karr, Office of War Information; chief aide to journalist Drew Pearson.

Venona transcripts

confirm the Senate Civil Liberties Subcommittee, chaired by former

Senator Robert

LaFollette, Jr., whom McCarthy defeated for election in 1946, had at least

four

staff members working on behalf of the KGB. Chief Counsel of the Committee

John Abt; Charles Kramer, who served on three other Congressional Committees; Allen

Rosenberg, who also

served on the National Labor Relations Board, Board of Economic Warfare

(BEW), the Foreign Economic Administration (FEA) and later argued cases before the

United States Supreme Court; and Charles Flato, who served on the BEW

and FEA, all were CPUSA members and associated with the Comintern.

While the underlying premise of Communists in the

government was true, many of McCarthy's

targets were not complicit in espionage.

Recent scholarship has established of 159 persons

investigated between 1950

and 1952, there is substantial evidence nine had assisted Soviet

espionage using

evidence from Venona or other sources. Of the remainder, while

not being directly

complicit in espionage, many were considered security risks.

Known security/loyalty risks

In June 1947, a

Senate Appropriations subcommittee addressed a secret memorandum

to Secretary

of State George Marshall, calling to his attention a condition that

developed

and was continuing in the State Department. The memo stated that

| “ | it was evident there was a deliberate, calculated program being

carried out not only to protect communist personnel in high places, but to reduce

security and intelligence protection to a nullity. On file in the department

is a copy of a preliminary report of the FBI on Soviet espionage activities

in the United States which involved a large number of State Department employees,

some in high official positions. | ”

|

Robert

E. Lee was the committee’s lead investigator and supervised preparation of the list.

The Lee list, also using numbers rather than names, was published in the proceeding

of the subcommittee.

The memorandum listed

the names of nine State Department officials and said that they

were "only

a few of the hundreds now employed in varying capacities who are protected

and

allowed to remain despite the fact that their presence is an obvious hazard to national

security." Ten persons were removed from the list by June 24. But from 1947 until McCarthy's

Wheeling speech in February 1950, the State Department did not fire one person as a

loyalty or security risk. In other branches of the government, however, more than 300

persons were discharged for loyalty reasons alone during the period from 1947 to 1951.

Most but not all of Senator McCarthy’s numbered cases were

drawn from the “Lee List”

or “108 list” of unresolved

Department of State security cases compiled by Lee for the

House Appropriations

Committee in 1947. The Tydings subcommittee also obtained

this list. In addition

to some of the person involved in espionage identified in the

Venona project listed above, there are other security and loyalty risks

identified correctly

by Senator McCarthy included in the following list:

- Robert Warren Barnett & Mrs. Robert Warren Barnett, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's

- Case #48 and #49 respectively and both are on Lee

list as #59;

- Esther Brunauer, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #47 and Lee list #55;

-

Stephen Brunauer, U.S. Navy, chemist in the explosive research division;

Stephen Brunauer, U.S. Navy, chemist in the explosive research division; - Gertrude Cameron, Information and Editorial Specialist in the U.S. State Department;

- McCarthy's Case

#55 and Lee list #65;

- Nelson Chipchin, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's list #23;

- Oliver Edmund Clubb, U.S. State Department;

- John Paton Davies, U.S. State Department, Policy Planning Committee;

- Gustavo Duran, U.S. State Department, assistant to the Assistant Secretary of State in

- charge of

Latin American Affairs, and Chief of the Cultural Activities Section of the

- Department

of Social Affairs of the United Nations;

- Arpad Erdos, U.S. State Department;

- Herbert Fierst, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's case #1 and Lee list #51;

- John Tipton Fishburn, U.S. State

Department; Lee list #106;

- Theodore Geiger, U.S. State Department;

- Stella Gordon, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #40 and Lee

list #45

- Stanley Graze, U.S. State Department intelligence; McCarthy's Case #8 and Lee list #8,

- brother of Gerald

Graze, confirmed in KGB Archives;

- Ruth Marcia Harrison, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #7 and Lee list #4;

- Myron Victor Hunt, U.S. State

Department; McCarthy's Case #65 and Lee list #79;

- Philip Jessup, U.S. State Department, Assistant Director for the Naval School of Military

- Government

and Administration at Columbia University in New York, Delegate to the U.N.

- in a number

of different capacities, Ambassador-at-large, and Chairman of the Institute

- of Pacific

Relations Research Advisory Committee; McCarthy's Case #15;

- Dorothy Kenyon, New York City Municipal Court Judge, U.S. State Department appointee

- as American

Delegate to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women;

- Leon Hirsch Keyserling, President Harry Truman's Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers;

- Mary Dublin Keyserling, U.S. Department of Commerce;

- Esther Less Kopelewich, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case

#24;

- Owen Lattimore, Board member of the communist-dominated Institute of Pacific Relations

- (I.P.R) and editor the I.P.R.’s journal Pacific Affairs;

-

Paul A. Lifantieff-Lee, U.S. Naval Department; McCarthy's Case #56 and Lee list #66;

-

Val R. Lorwin, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #54 and Lee list #64;

Val R. Lorwin, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #54 and Lee list #64; -

Daniel F. Margolies, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #41 and Lee list #46;

Daniel F. Margolies, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #41 and Lee list #46; -

Peveril Meigs, U.S. State Department; Department of the Army; McCarthy's

Peveril Meigs, U.S. State Department; Department of the Army; McCarthy's - Case #3 and Lee list #2;

-

Ella M. Montague, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #34 and Lee list #32;

- Philleo Nash, Presidential Advisor, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman administrations;

- Olga V. Osnatch, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #81 and Lee list #78;

-

Edward Posniak, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case Number 77;

Edward Posniak, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case Number 77; - Philip Raine, U.S. State Department, Regional Specialist; McCarthy's Case #52 and Lee list #62;

Robert Ross, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #32 and Lee list #30;

Robert Ross, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #32 and Lee list #30; Sylvia Schimmel, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #50 and Lee list #60;

Sylvia Schimmel, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #50 and Lee list #60;- Frederick Schumann, contracted by U.S. State Department as lecturer; Professor

- at Williams College; not

on Lee list;

- John S. Service, U.S. State Department;

- Harlow Shapley, U.S. State Department appointee to UNESCO, Chairman of the

- National Council of Arts,

Sciences, and Professions;

- William T. Stone, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #46 and Lee list #54;

- Frances M. Tuchser, U.S. State

Department; McCarthy's Case #6 and Lee list #6;

- John Carter Vincent, U.S. State Department; McCarthy's Case #2 and Lee list #52;

-

David Zablodowsky, U.S. State Department & Director of the United Nations

David Zablodowsky, U.S. State Department & Director of the United Nations

- Publishing Division. McCarthy's

Case #103;

Attacks on McCarthy

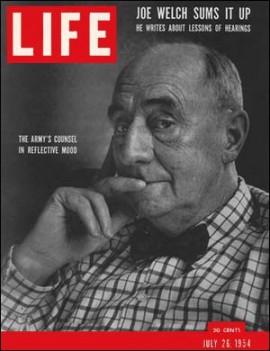

One of the most prominent attacks on Senator McCarthy was an episode of the TV

documentary series See It Now, hosted by Edward R. Murrow, which was broadcast

on March 9, 1954. By the time Murrow produced his "See

It Now" assault on Senator

McCarthy in 1954, the senator had been under

almost constant vicious attack for four

years. According to McCarthy biographer

Arthur Herman, Murrow and his staff had

spent two months carefully editing film

clips to portray McCarthy in the worst possible

light. There were no clips showing

McCarthy in a professional manner. Despite Murrow's

claims, this "was not

a report at all but instead a full-scale assault, employing exactly the

same

techniques of 'partial truth and innuendo' that critics accused McCarthy of using."

The episode consisted largely of clips of McCarthy in the most unflattering context, including

"belching and picking his nose".

In

these clips, McCarthy accuses the Democratic Party of "twenty years of treason" because

of the Democratic Party's concessions

to the Soviet Union at the Yalta conference and

Potsdam conference, describes the American Civil Liberties Union as "listed as 'a front

for, and doing the work of,' the Communist Party,"

and berates General Zwicker for Zwicker's

claim that he would protect any other

general who promotes Communists within the military.

Murrow also portrays a Pentagon

coding room employee, Annie Lee Moss as an innocent

victim of McCarthy even though it was later established that

the FBI had warned the

Army and the Civil Service Commission about her Communist Party connection.

However, even some McCarthy critics were

outraged by this one-sided presentation.

Consistent McCarthy critic, John Cogley

of Commonweal, "sharply attacked Murrow

and his producers for their distorted summary

and selected use of video clips." Cogley

commented that a different selection

of footage could have easily portrayed McCarthy in

an extremely positive light

and then further warned against the misuse of television in

this fashion. He

and another McCarthy critic from the Saturday Review

agreed that it

"was not a proud moment for television journalism".

To counter the negative publicity, McCarthy appeared on See It Now on April 6, 1954,

and presented his case in order to clarify the misconceptions that Murrow had televised.

McCarthy countered that his committee, "has forced out of government, and out of important

defense plants, Communists engaged in the Soviet conspiracy." McCarthy went on to say,

"For example, 238 witnesses were examined [in] public session; 367 witnesses examined

[in] executive session; 84 witnesses refused to testify as to Communist activities on

the ground that, if they told the truth, they might go to jail; twenty-four witnesses with

Communist backgrounds have been discharged from jobs [in] which they were handling

secret, top-secret, confidential material, individuals who were exposed before our committee."

McCarthy also exposed Murrow's left-wing background and previous associations with

Communist organizations.

The

Murrow report, together with the televised Army-McCarthy hearings of the same year,

and

four years of consistent anti-McCarthy media reporting were the major causes of a

nationwide popular opinion backlash against McCarthy. However, well-known broadcaster

Eric Sevareid said the Murrow assault "came very late in the day.... The youngsters

read back, and they think only one person in broadcasting and the press stood up to

McCarthy, and this has made a lot of people feel very upset, including me, because that

program came awfully late."

Even Murrow

discounted his role in the decline of Senator McCarthy's popularity. Murrow

stated,

"My God, I didn't do anything. (Times columnist) Scotty Reston and lot of guys have

been writing like this, saying the same things, for months, for years. We're bringing up the rear."

Nevertheless, despite the deceptive nature of the See It Now

program and the late date

in which it appears, anti-McCarthy historians have

credited and celebrated Murrow as

playing a major role in damaging Senator McCarthy's

campaign to remove security risks

from the U.S. government.

Senate opposition

to McCarthy

While over the previous few years, Senator McCarthy had withstood countless biased and

unsubstantiated attacks by Liberals, Communists, etc., who sought to prevent him from

damaging their causes any further; the

organized and co-ordinated effort between the two

groups to remove McCarthy from

his Chairmanship and officially condemn him began in

March 1954.

Senate

opposition

On March 9, 1954 a fellow conservative and anti-communist Republican Senator,

Ralph E. Flanders of Vermont, gave a speech criticizing what he felt was Senator

McCarthy’s "misdirection

of our efforts at fighting communism” and his role in “the loss

of

respect for us in the world at large.” Flanders felt the nation should pay more attention

looking outwards at the “alarming world-wide advance of Communist power” that would

leave the United States and Canada as “the last remnants of the free world.” Eisenhower

Administration cabinet officials told Flanders to “lay off,” while President Eisenhower sent

Flanders a brief note of appreciation for his speech, but did not otherwise confer with him

or explicitly support him. In a June 1, 1954 speech, Flanders emphasized how the Soviet

Union was winning military successes in Asia without risking its own resources or men,

and said this nation was witnessing "another example of economy of effort...in the conquest

of this country for communism." He added, "One of the characteristic elements of communist

and fascist tyranny is at hand as citizens are set to spy upon each other." Flanders

told the

Senate that McCarthy's "anti-Communism so completely parallels that

of Adolf Hitler as

to strike fear into the hearts of any defenseless minority"; he accused

McCarthy of spreading

"division and confusion" and saying, "Were

the Junior Senator from Wisconsin

in the pay of the Communists he could not

have done a better job for them."

On June 11,

1954 Flanders introduced a resolution charging McCarthy “with unbecoming

conduct" and calling for his removal from his committee chairmanship. Upon the advice

of Senators John Sherman Cooper and J. William Fulbright and legal assistance from

the National Committee for an Effective Congress, a liberal organization, he modified

his resolution to “bring it in line

with previous actions of censure.” After introducing his

censure motion,

Flanders had no active role in the ensuing Watkins Committee hearings.

Flanders

bore McCarthy no personal animosity and reported that McCarthy

accepted his invitation

to join him at lunch after the hearings had taken place.

Watkins Committee

Ultimately, McCarthy

was accused of 46 different counts of allegedly improper conduct

and another

special committee was set up, under the chairmanship of Senator Arthur Watkins,

to study and evaluate the charges. This was to be the fifth investigation

of Senator McCarthy

in five years. This committee opened hearings on August 31,

1954. After two months of

hearings and deliberations, the Watkins Committee recommended

that McCarthy be censured

on only two of the original 46 counts. The committee

exonerated McCarthy on all

substantive charges.

On November 8, 1954, a special session of the Senate convened to debate the two charges.

The charges to be debated and voted on were: 1) That Senator McCarthy had "failed to

cooperate" in 1952 with the Senate Subcommitee on Privileges and Elections that was

looking into certain aspects of his private and political life in connection with a resolution

for his expulsion from the Senate; and 2) That in conducting a senatorial

inquiry, Senator McCarthy had "intemperately abused" General Ralph Zwicker.

The Zwicker count was dropped by the full Senate on the grounds that McCarthy's conduct

was arguably "induced" by Zwicker's own behavior. Many senators felt that the Army

had

shown contempt for committee chairman McCarthy by disregarding his letter

of February 1,

1954 and honorably discharging Irving Peress the next day. So,

for this reason, the

Senate concluded that McCarthy's conduct toward Zwicker

on February 18 was justified.

Therefore, the Zwicker

count was dropped at the last minute and was replaced with this

substitute charge:

2) That Senator McCarthy, by characterizing the Watkins Committee

as the "unwitting

handmaiden" of the Communist Party and by describing the special Senate

session as a "lynch party" and a "lynch bee," had "acted contrary to senatorial ethics and

tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the

constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity."

On December 2, 1954, even though more than a dozen senators told McCarthy that they

did not want to vote against him but had to do so because of the enormous pressure being

put on them by the Eisenhower Administration and by leaders of both political parties, the

Senate voted to "condemn"

Senator Joseph McCarthy on both counts by a vote of 67 to

22. The Democrats

voted unanimously in favor of condemnation and the Republicans split evenly.

Resolution condemns

McCarthy

The resolution condemning Senator McCarthy has been criticized as a ridiculous attempt

to silence the strongest voice in the Senate investigating security and loyalty risks in the

U.S. government. When examined closely, the two counts used in condemning McCarthy

were hopelessly flawed.

In analyzing the

first count, "failure to cooperate with the Subcommittee on Privileges

and

Elections", the fact is that the subcommittee never subpoenaed McCarthy, but

only

"invited" him to testify. One senator and two staff members resigned from the

subcommittee because of its dishonesty towards McCarthy. In its final report dated

January 2, 1953, the subcommittee, stated that the matters under consideration

"have become moot by reason of the 1952 election." Up until this moment in U.S.

history, no senator had ever been punished for something that had happened in a

previous Congress or for declining an "invitation" to testify. Therefore, the first count

was a complete fraud and nothing more than a trumped up charge in order to damage

Senator McCarthy.

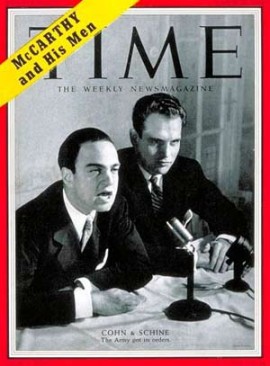

The

second count was even more flawed than the first. McCarthy was condemned for

opinions

he had expressed outside the Senate when he criticized the Watkins Committee

and

the special Senate session. In an editorial by David Lawrence in the June 7, 1957

issue

of U.S. News & World Report, other senators had accused McCarthy of lying under

oath, accepting influence money, engaging in election fraud, making libelous and false

statements, practicing blackmail, doing the work of the communists for them, and engaging

in a questionable "personal relationship" with Roy Cohn and David Schine. However,

these other Senators were not censured for acting

"contrary to senatorial ethics" or for

impairing the "dignity"

of the Senate. Only Senator McCarthy would be held responsible

for his words.

Final

years

The flag-draped coffin containing the body of Senator McCarthy is carried up the steps

of the U.S. Capitol for funeral services in the Senate chamber after an earlier service at St. Matthew's Cathedral, May 6,

1957. Photograph courtesy of The Post-Crescent

Senator McCarthy's power and clout to continue the search for Communists

in positions

of power in America was severely curtailed. After the Republicans

lost control of the Senate

in 1954, McCarthy, now a member of the minority Party,

had to depend on public

speeches to continue his campaign of warning the American

people to the danger of

Communism. He did this in a number of important addresses

during those two and a half years.

In January 1957,

McCarthy and his wife, Jean, adopted a baby girl and named her, Tierney.

Unfortunately,

several months later, McCarthy died of acute hepatitis, likely brought on by

his lifelong struggle with alcoholism, in Bethesda Naval

Hospital on May 2, 1957, at the age of 48.

McCarthy

was given a state funeral attended by 70 senators. McCarthy was the first senator

in 17 years to have funeral services in the Senate chamber. Thousands of people

viewed

the body in Washington D.C. and it is estimated more than 30,000 people

from

Wisconsin filed through St. Mary's Church in the senator's hometown of Appleton,

Wisconsin, where the clergy performed a Solemn Pontifical Requiem before more than

100 priests and 2,000 others. Three senators, George Malone, William E. Jenner, and

Herman

Welker, had flown from Washington D.C. to Appleton on the plane carrying

McCarthy's

casket. Robert Kennedy attended the funeral in Wisconsin. McCarthy was

buried in St. Mary's Parish

Cemetery in Appleton and was survived by his wife, Jean, and

their adopted daughter,

Tierney.

Retrospective views on McCarthy

- In her popular book, Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold

- War to the War on Terrorism, Ann Coulter said of McCarthy:

- "A half century later, when the only people who call themselves Communists are

- harmless cranks, it is difficult to grasp the importance of McCarthy's crusade. But

- there's a reason 'Communist' now sounds about as threatening as 'monarchist'

- -- and it's not because of intrepid New York Times editorials denouncing McCarthy

- and praising Harvard educated Soviet spies. McCarthy made it a

-

disgrace to be a Communist. Domestic Communism could never recover."

When Ann Coulter asked Fox News’ Bill O'Reilly to identify a McCarthy-tormented

innocent, O'Reilly responded with Dalton Trumbo, one of House Un-American Activities Committee's

(HUAC) “Hollywood Ten”, not realizing HUAC investigated CPUSA infiltration in Hollywood

and called “the Hollywood

Ten” of writers, directors and producers to testify in

1947. McCarthy

did not start his crusade against Communism until 1950.

- In 1953-54, McCarthy had been investigating lax security in the top secret facility at

- Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey. He was attacked by liberals and Communists on the

- grounds that there were no security problems at Ft. Monmouth. Years later, in

- addressing the reason why the U.S. Army's top-secret operations at Fort Monmouth

- were quietly moved to Arizona, Senator Barry Goldwater, in his 1979 book With

- no apologies: The personal and political memoirs

of United States Senator

- Barry M. Goldwater, Goldwater stated:

- "Carl Hayden, who in January

1955 became chairman of the powerful

- Appropriations Committee of the United

States Senate, told me privately

- Monmouth had been moved because he and other

members of the majority

- Democratic Party were convinced security at Monmouth

had been penetrated.

- They didn't want to admit that McCarthy was right in

his accusations. Their

- only alternative was to move the installation from

New Jersey to a new location

- in Arizona."

Even though McCarthy's

investigations proved that his suspicions were right, for many

years afterward

and continuing to this day, liberals have spread the falsehood that McCarthy

had

found nothing at Fort Monmouth.

- Before the 1989 release of Carl Bernstein's book, Loyalties: A Son's Memoir, Albert

- Bernstein, Carl's father, expressed

dismay at the revelations that the book would make

- regarding Communist infiltration of

the U.S. government and other sectors of American

- society. Albert Bernstein stated:

- "You're going to prove

[Sen. Joseph] McCarthy was right, because all he

- was saying is that the system

was loaded with Communists. And he was

- right. I'm worried about the kind

of book you're going to write and about

- cleaning up McCarthy. The problem

is that everybody said he was a liar;

- you're saying he was right. I agree

that the Party was a force in the country."

Both Albert Bernstein and Sylvia Bernstein, Carl's mother, had both been Communists

since the 1940s. Albert Bernstein was a Union activist, while Sylvia Bernstein was a

secretary for the War Department in the 1930s and, during the Clinton Administration,

volunteered in the White House, answering letters that were addressed to Hillary Clinton.

During the 1950s, Sylvia Bernstein invoked the Fifth Amendment to avoid revealing

her

party ties to Congress but worked openly in assisting convicted spies Julius Rosenberg

and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed in 1953 for espionage.

It should be pointed out how many people followed McCarthy on his crusade, and that

many pro-Americans still do. The majority of the sources that discredited Senator McCarthy

originated from a large assault by the liberal media that managed to sway the

majority of

Americans against him at that time. While many Americans –

liberals and conservatives–

use McCarthy's name in a negative connotation,

such references are unfair to McCarthy.

Quote

- "if liberals were merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate

- that at least some of their decisions would serve America's interests."

Bibliography

Buckley,

William F. McCarthy and His Enemies (1954),

a major

statement by a young conservative

Crosby, S.J., Donald F. God, Church and Flag:

Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Catholic Church,

Fried,

Richard M. Nightmare in Red:

- Griffith, Robert. The Politics

of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate 1987 online edition

- Herman, Arthur Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life

and Legacy of America’s

- Most Hated Senator (2000). excerpt and text search, very favorable to McCarthy

- Latham, Earl Communist

Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy. (1969).

- O'Brien, Michael. McCarthy and McCarthyism in Wisconsin. (1981)

- Oshinsky, David M. A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy (1983), standard biography excerpt and text search

- Reeves, Thomas C. The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy:

A Biography (1982),

- standard biography by a leading conservative scholar

McCarthyism

- Klehr, Harvey, John Earl Hayes and Fridrikh Igorevich Firsov. The Secret World

of

- American Communism (1995) excerpt and text search

- Klehr, Harvey, and Ronald Radosh. The Amerasia Spy

Case: Prelude to McCarthyism

- (1996), suggests that Soviet spying in the postwar United

States was extensive and

- that in the case of the arrest of the editors of the Amerasia

magazine, and others, in

- 1945, naive liberals in the Justice and State departments blocked

efforts to bring the

- spy ring to justice. excerpt and text search

- Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Earl Raab. The Politics

of Unreason: Right Wing

- Extremism in America, 1790-1970 (1970) (Chap. 6

"The 1950's: McCarthyism")

- online edition

- Morgan, Ted. Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century

America. 2003. 685 pp.

- excerpt and text search

- O'Reilly, Kenneth. Hoover and the Un-Americans: The

FBI, HUAC, and the

- Red Menace 1983

- Ottanelli, Fraser M. The Communist Party of the United States: From the Depression

- to World War II 1991 excerpt and text search

- Rausch, Scott Alan. "McCarthyism and Eisenhower's

State Department, 1953-1961."

- PhD dissertation U. of Washington 2000. 231 pp.

DAI 2000 61(6A): 2438-A. DA9976046

- Schrecker, Ellen.

"McCarthyism: Political Repression and the Fear of Communism."

- Social Research

2004 71(4): 1041-1086. Issn: 0037-783x Fulltext: in Ebsco;

- summarizes her books on the

subject

- Schrecker, Ellen. Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism

in America (1998)

- excerpt and text search

- Schrecker, Ellen. The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief

History with Documents.

- (2d ed. 2002). 308 pp. excerpt and text search

- Tanenhaus, Sam. Whittaker Chambers: A Biography

(1998) excerpt and text search

- Theoharis, Athan. Chasing Spies: How the FBI Failed

in Counterintelligence but

- Promoted the Politics of McCarthyism in the Cold

War Years. (2002). 307 pp.

- excerpt and text search

- Weinstein, Allen, and Vassiliev, Alexander. The Haunted

Wood: Soviet Espionage

- in America: The Stalin Era (1999) excerpt and text search

Media

issues

- Doherty, Thomas. Cold War, Cool

Media: Television, McCarthyism, and American

- Culture (2003) excerpt and text search

- Dussere, Erik. "Subversion in the Swamp: Pogo and

the Folk in the McCarthy Era."

- Journal of American Culture2003 26(1): 134-141.

Issn: 1542-7331 Fulltext: in Ebsco

- Murphy, Brenda. Congressional

Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film,

- and Television. (1999).

310 pp. excerpt and text search

- Sbardellati, John and Shaw, Tony. "Booting a Tramp:

Charlie Chaplin, the FBI, and

- the Construction of the Subversive Image in Red Scare

America." Pacific Historical Review 2003 72(4): 495-530. Issn: 0030-8684 in JSTOR

- Strout, Lawrence N. Covering McCarthyism: How the

Christian Science Monitor

- Handled Joseph R. McCarthy, 1950-1954. 1999.

171 pp. online edition

Primary

sources

- Joe McCarthy. Major Speeches and

Debates of Senator Joe McCarthy Delivered in

- the United States Senate, 1950-1951

U. S. Government Printing Office, 1953 online edition

- Joe McCarthy. McCarthyism: The Fight for America

1952 online edition

- Fried, ed. Albert. McCarthyism: The Great American

Red Scare: a Documentary

- History 1997 online edition

- Schrecker, Ellen W. "Archival Sources for the Study

of McCarthyism," The Journal

- of American History, Vol. 75, No.

1 (Jun., 1988), pp. 197–208 at JSTOR

See also