Crystal City Texas

Housing all three Axis nationalities, Crystal City (Family)

Internment Camp was intended to be populated by people of Japanese ancestry and their immediate families. However, on

December 12, 1942, the camp’s first internees to arrive were a mix of German Americans and German Enemy Aliens. On

February 12, 1943, the first group of Latin Americans arrived––also Germans––deported from Costa

Rica. On March 17, 1943, the first group of Japanese American internees arrived. The Immigration and Naturalization (INS)

planned to transfer all German internees to another camp, but the German spokesman asked camp officials if they could remain

because their living conditions here were far better than at previous confinement sites they were held at.

From its inception in mid-1942 through June 1945, Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp

interned 4,751 (this included 153 people born in the camp). The camp’s population peaked at 3,374 on December 29,

1944, more than two thirds of which were of Japanese nationality or ancestry. Approximately 11,507 German Americans were

interned in the U.S. during the war, accounting for 36 percent of the total internments under the DOJ Alien Enemy Control

Unit Program. In addition, an estimated 4,500 ethnic Germans and Italians from Latin America were brought to the U.S. during

the war, as part of the Department of State’s Special War Problems Program, with many held at Crystal City. Millions

of native-born Italians––later naturalized––and their American-born children lived in the U.S. when

the country went to war with the Axis in 1941. In addition, there were also many Italian Enemy Aliens residing in the U.S.,

estimated at nearly 600,000. However, the percentage of Italians, classified as Enemy Aliens and interned during the war

was far smaller than those interned from the Japanese and German American communities. Following the surrender of Fascist

Italy in 1943, most Italian American and Enemy Alien internees were paroled or outright released by the end of that year.

A few Italian Latin Americans, held in very small numbers at Crystal City, remained well after the end of the war.

By late 1942, the U.S. Army realized it needed to focus the efforts of it's Provost Marshal

General's Office on the expected task of guarding hundreds of thousands of Axis Nations [Japan, German, and Italy] prisoners

of war. In response, the DOJ gave the INS further authority to house potentially dangerous Enemy Aliens (including U.S.

citizens) at internment camps throughout the U.S. Early in the war, many detained Enemy Aliens were fathers, and the INS

faced an increasing number of requests from wives and children volunteering to be interned so they might be reunited with

the head of their households. This need to house families together was the genesis of theCrystal

City (Family) Internment Camp. In April 2013, the THC conducted a low-invasive archeological survey in an effort

to gain a better understanding of the camp’s history. This survey is funded through a 2012 grant from the National

Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program, and will aid the THC with its National Register

of Historic Places nomination for the confinement site.

What Did The Confinement Site Look Like?

In

Crystal City, the INS looked for a site that was removed from important war production facilities and had good existing water

and electrical services. Noting the pressing need for the camp to open, the INS looked at Crystal City, where the U.S. Government

already owned a large portion of land. During the Great Depression, the Farm Security Administration acquired land on the

outskirts of this small southwest Texas town and built approximately 150 buildings to house migratory agricultural workers.

In early 1942, the U.S. military reviewed the facility as a potential location to establish a training site, but that never

materialized.

When the internment camp opened

in December 1942, the site was approximately 240 acres in size, with 41 small three-room cottages and 118 one-room shelters

(measuring 12x16 feet). Twelve of the original cottages were left outside the “fenced area” (100 acres in size)

for use by official personnel and their families. With an expected increase in population and need for more housing, the

DOJ confiscated an additional 50 acres to the south of the “fenced area,” dug a water well, and constructed

a self-contained sewer system.

The INS purchased

the camp’s utilities from the City of Crystal City, Central Power and Light, Texas Gas, and the Del Rio and Wintergarden

Telephone Company. Within the fenced area, the INS constructed with the assistance of the initial German internees and the

support of Japanese American internees––housing units consisting of 61 duplex, 62 triplex and 96 quadruple design

barracks, and 15 additional three-room cottages for internees. As more and more internees arrived, the INS added 103

“Victory Huts” around the camp.

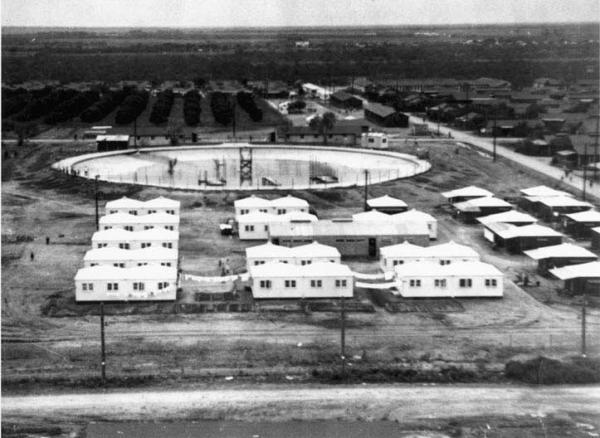

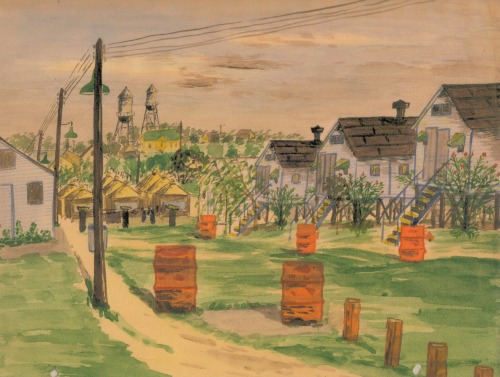

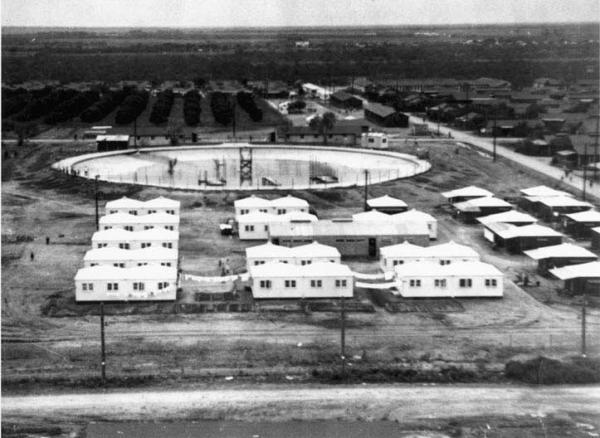

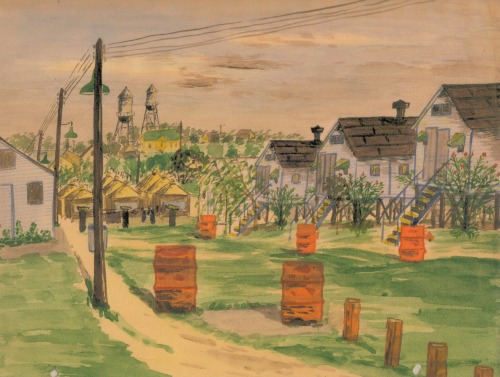

View of Victory Huts, looking south (source: UTSA's Institute of Texan Cultures)

The Third Geneva Convention––Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (1929)––also

applied toward the treatment of Alien Enemies interned in INS camps, monitored by the International Red Cross. These provisions

applied to the amount of food, living space, and clothing that each internee received, often better than the housing and

living conditions of the rationing public in Zavala County, Texas. To comply with international law and promote as positive

an environment as possible, the INS designed the internment camp much like a small community with numerous buildings for

food stores, auditoriums, warehouses, administration offices and a 70-bed hospital, places of worship, a post office, bakery,

barber shop, beauty shop, school system, a Japanese Sumo wrestling ring, and a German beer garten. Internees printed

four camp newspapers: the Crystal City Times (English), the Jiji Kai (Japanese), Los Andes (Spanish)

and Das Lager (German).

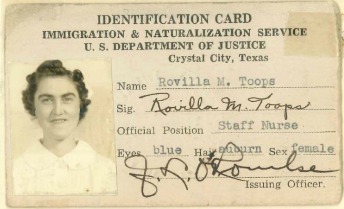

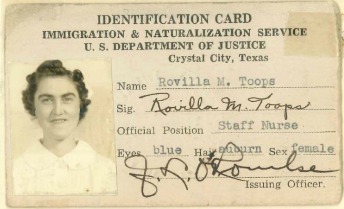

Crystal City

Family Internment Camp was staffed by local civilian employees in secretarial and clerical positions, civilian nurses and

doctors, a professional cadre of INS administrators and Border Patrolmen. Later in the war, the INS employed local men from

Crystal City as guards. J. L. O’Rourke was the officer in charge. Under O’Rourke internment camp functions were

allocated to several key divisions: the Administrative Service, Surveillance, Internal Security and Internal Relations [originally

called the Liaison Division], Maintenance, Construction and Repair, Education, and Medical.

Camp Staff Identification Card (Source: Toops Family Collection)

The

“fenced area” had a 10-foot high barbed wire barrier around the internee section, six guard towers with one located

on each corner and half-way down the west-to-east axis, an armed guard who patrolled the fence line, and an internal security

force patrolling both the Japanese and German sections of the camp.

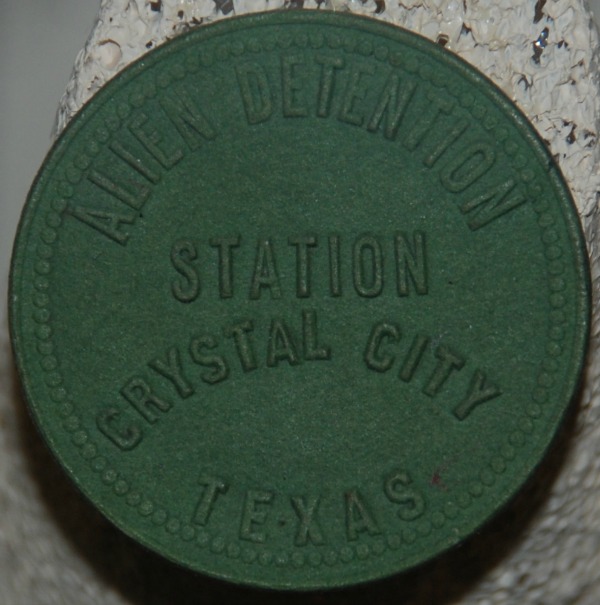

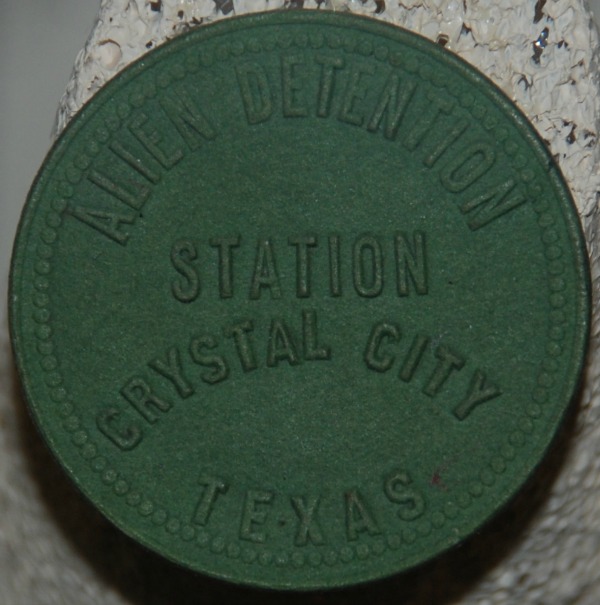

In accordance with the Third Geneva Convention, no internee had to perform manual labor against their will. For

those who wanted to work, they could earn 10 cents per hour up to a maximum of $4 per week. Jobs ranged from store clerks,

hospital staff, librarians, laundry workers, shoe repairmen, furniture and mattress factory positions, janitors, barbers,

and beauticians. Select internees worked in the INS administration offices. Internees with agricultural experience worked

in the camp’s internal orange orchard, vegetable gardens, and the surrounding agricultural fields dedicated to the

camp. In an effort to prevent internees from stockpiling cash in the event of an escape attempt, camp scrip was issued to

internees. The camp scrip was pressed paper and plastic tokens that resembled coins or poker chips, but were not legal tender.

There were no reported escape attempts, successful or otherwise, from Crystal City Family Internment Camp.

Camp Scrip Token

One of the programs for internees established at Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp was an accredited education

program. Robert Clyde “Cy” Tate was hired to supervise the school system. Prior to joining the staff in 1943,

Tate had served as the Crystal City High School principal. One of Tate’s initial objectives was to recruit qualified

teachers to move to Crystal City and work in the camp’s schools. This was no easy task due to the uncertainty of the

work’s duration and the remoteness of Crystal City. Challenged by the fact that each student was a transfer, Tate

strived to meet state regulations concerning proper textbooks, teaching materials, and classroom space requirements per

pupil.

Tate established three types

of schools: the American (called Federal) School, the Japanese School, and the German School. Each school provided an elementary,

junior high, and high school education. The Federal School offered an American-style education; the Texas State Board of

Education inspected the schools and granted full accreditation for all courses taught. Some graduates eventually went on

to U.S. colleges. Both the Japanese and German schools provided students with a background in their ancestral culture and

language. Both Japanese and German American and Latin American internees served as teachers for non-federal schools and

designed their own curriculum. While meeting the cultural needs of internees, the Japanese and German School systems assisted

future voluntary and non-voluntary repatriates for life––after they were exchanged for U.S. and Allied personnel––in

their ancestral home lands.

Federal High School looking north (source: Carroll Brincefield)

Federal High School, and its feeder school, Federal Elementary, provided students with both academic and athletic

opportunities. Multiple softball and basketball and two football teams formed between 1943 and 1946, the year the school

system closed. In 1944-1945, Federal High School students produced their own yearbook, the Roundup; published a

school newspaper, the Campus Quill; held a prom; and participated in commencement exercises.

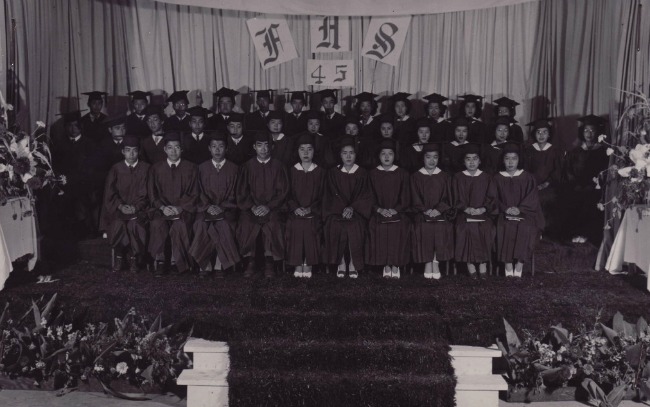

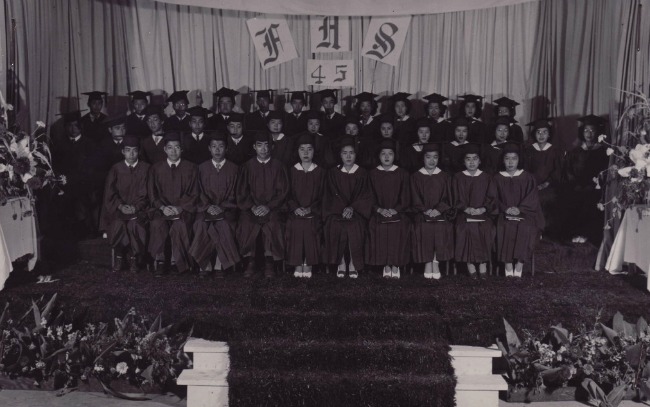

1945 Federal High School Graduating Class (source: NARA RG 85, Entry 276 Box 46 - Folder 602?032)

German Student Internees (source: Eb Fuhr)

A source of recreation and community, the camp’s Swimming Pool/Irrigation Reservoir was the camp’s largest

defining feature (minus the security fence) and today is the most extant resource left of this nationally significant site.

The 250-foot-wide-pool was designed by Italian-Honduran civil engineer Elmo Gaetano Zannoni. With German internees providing

the labor, a former swamp was drained, cleared of snakes, expanded and paved over.

German Internees Building Camp

Swimming Pool (source: UTSA's Institute of Texan Cultures)he German and Japanese bathhouses were built separately to allow

Japanese internees and their German and Italian internee counterparts separate and equal access to the community swimming

pool in congruence with the U.S.’ obligation as a signatory of the Third Geneva Convention, which was applied toward

Alien Enemies and reads, “The Detaining Power shall assemble prisoners of war in camps or camp compounds according

to their nationality, language and customs …”

The pool was enjoyed by children throughout the internment camp, and was a welcome relief from the hot summer sun.

The pool’s deep end was filled-in with dirt after the war and today is distinguishable as a grass half-circle. The

deep end of the pool facilitated three diving platforms. Between the deep end and shallow end are the metal piling remains

of a safety cable that extended across the diameter of the pool, separating deep water from shallow. Tragically, in 1944,

two Japanese Peruvian girls drowned while swimming in the pool when they slipped past the safety cable. Former Japanese

American internee, Bessie Masuda from California (whose family was reunited with her father at Crystal City), commented

in an oral history interview with the Texas Historical Commission on the tragic drowning of two young Japanese Peruvian girls

who ventured into the deep end of the pool, “… I was wading with my friends in the pool and we actually

saw the girl drowning in the deep end of the pool. We all grabbed hands and tried to reach them, but the floor was too slippery

for us. It was so sad that we couldn't help…”

__________________________________

To

the north of the Crystal City Family Internment Camp pool was the temporary Victory Hut section of the camp (see photo above)

where mostly Japanese Peruvians were first quartered upon arriving at the camp. Victory Huts were four sided wooden walled

military tent structures, purchased inexpensively, and erected rapidly for temporary emergency housing. Internee housing

for the most part offered families individual cooking facilities, cold running water, and oil stoves. This section of the

camp served as temporary housing for newly arriving internees as current residing internees were processed out for parole

or repatriation. Many Latin American internees, regardless of nationality, primarily spoke Spanish and had difficulty communicating

in the camp through English, Japanese, and German.

Japanese, German, & Italian Enemy Alien Internment & Repatriation

The interment camp’s population expanded throughout the war, and ultimately consisted

of Japanese (Issei), Japanese Americans (Nisei), German American citizens, German nationals, Italian nationals, as well

as Latin American Japanese, German and Italian, and a small group of Indonesian sailors.

S.S. Gripsholm in New York City (source: NARA RG 59, Box 1)

Leaving the U.S. during a repatriation

voyage (source: NARA RG 59, Box 1 - Folder 4)

German children internees on board a repatriation voyage (source: NARA RG 59, Box 1 - Folder 5) during the war, the

chartered Swedish ship, the SS Gripsholm sailed from the U.S. with internees from INS camps across the U.S. Two

massive movements from Crystal City took place in February 1944 and December 1944/January 1945. Many of the internees held

at Crystal City were now forced with trying to make a life in Germany or Japan on the brink of collapse as World War II

wound down. By June 30, 1945, with Germany and Italy knocked out of the war, and Japan less than two months away from unconditionally

surrendering to the Allies, Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp still had an internee population of 3,316. As the war

drew to a close, U.S. authorities were faced with the problem of managing the internees still confined across the country.

Part of the problem lay in how the internees should be designated. Those who voluntarily agreed to be sent back to their

country of national origin were considered for possible return to the U.S. in the future. Included in this group were the

American-born children of Axis nationals. The internees who did not volunteer or who were considered dangerous were classified

as deportees and could not return to the U.S. permanently. By December 1945, approximately 1,260 Japanese Peruvians were

exchanged out of Crystal City––600 to Hawaii and 660 to Japan––because Peru would not take them

back after the war. Many Japanese Peruvians had to wait nearly two years after the war ended, caught in a legal limbo before

their release. To that end, the INS encouraged remaining Japanese internees to find a sponsor after parole. A canning and

farming company at Seabrook Farms, New Jersey sponsored and hired the majority of the remaining internees.

___________________________________

The Crystal City Family Internment Camp closed on February 27, 1948, nearly 30 months after the end of the war on

September 2, 1945. In November 1948, the Crystal City Independent School District purchased 90 acres of the camp, primarily

within the fenced area, from the War Assets Administration. To the north and east of the fenced area is where the camp’s

athletic fields were located during the war. In 1952, the city purchased this portion of the camp to establish an airfield.

Today, eight distinct panels––dedicated by the Texas Historical Commission

and the City of Crystal City in November 2011––make up an interpretive trail at the former confinement site.

Heritage tourists looking to learn more about the site should stop by the Crystal City Memorial Public Library

located next to City Hall at 101 E. Dimmit Street and request a copy of the free brochure that accompanies the interpretive

signage project.

To learn more about Texan involvement

in World War II please visit the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg.

Oral History Interviews

THC historians have conducted oral history interviews with former Japanese, German, and

Italian (U.S. citizen and Enemy Aliens) interned at the Crystal City confinement site, as well as a number of U.S. citizens

who worked at the camp or lived in Crystal City during World War II. Interview subjects and transcripts for these interviews

are available below. Additional inquiries about this collection should be directed to the Military History Program Coordinator

at militaryhistory@thc.texas.gov.

Seiji Aizawa

U.S. citizen and former War Relocation Authority internee who visited his family while they were held at Crystal

City (Family) Internment Camp during the war. Aizawa Transcript

Heidi (Gurcke) Donald

Former German-Costa Rican whose family was arrested and deported by the Costa Rican government during the war. Her

family was held at Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp beginning in 1943. Donald Transcript

JoAnna Howell U.S.

citizen born in Texas during World War II. The Howell family was taken into custody in Fort Worth in December 1941, separated

from each other, and eventually reunited in Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp. Howell Transcript

Art Jacobs

U.S. citizen from New York held with his family at Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp during the war. He was

exchanged/repatriated to Germany and eventually returned to the United States after the war. Jacobs Transcript

Haru Kuromiya

Japanese American internee from California held along with her family at Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp during

the war. Kuromiya Transcript

Bessie Masuda

Japanese American internee from California. Her family was reunited with her father at Crystal City (Family) Internment

Camp during the war. Masuda Transcript

Audrey Moonyeen (Neugebauer) Thornton

Born in London, England, she and her British mother and German father left Venezuela

during the war for Costa Rica, where they were arrested and deported to the U.S. Her family was interned at Crystal City

(Family) Internment Camp during the war. Thornton Transcript

Elizabeth Yarborough

U.S. citizen born in Texas. She lived and worked in Crystal City during the war and commented on the confinement

site from the perspective of “the other side of the fence.” Yarborough Transcript

Kennedy, Texas

Kenedy Enemy Alien Detention Station

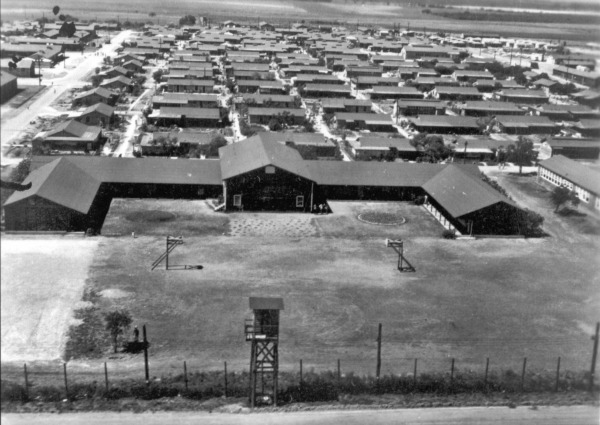

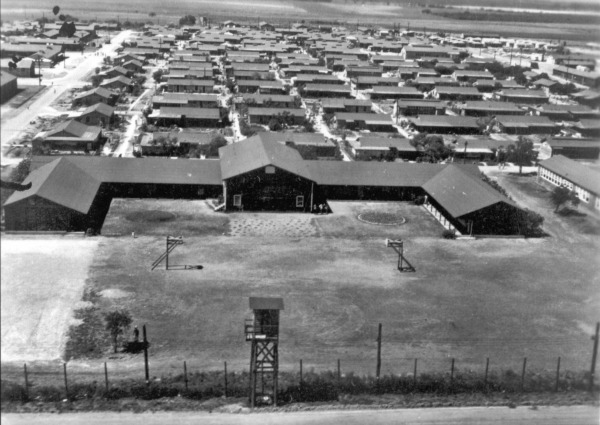

Under different names, organizations, and even two World Wars, Camp Kenedy has had a

long and storied service life. During World War I, the site served as an Army training post. During the Great Depression,

the site served as Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp #3806. In March 1942, the site was transferred from the CCC to

the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), and the Kenedy Alien Detention Camp received its first internees on April

21, 1942.

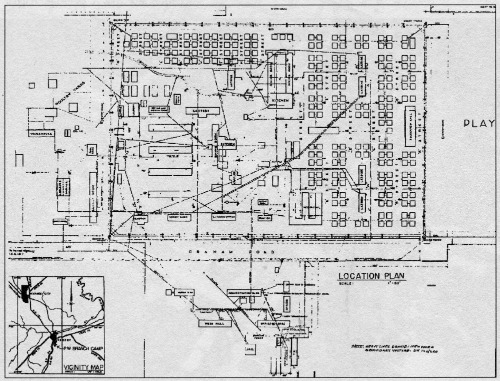

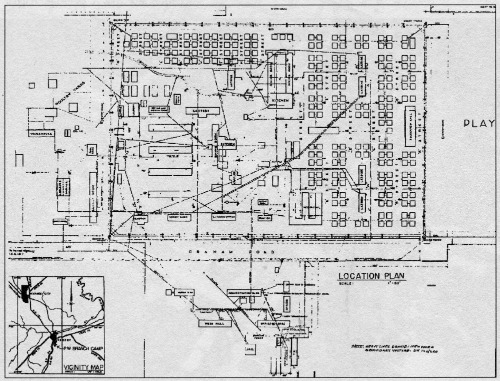

Map of Camp Kenedy after conversion to prisoner of war camp (source: Fort Sam Houston Museum/Judge Robert

H. Thonhoff)

The site was designated to hold detainees that the Department of State brought in from Latin America. The first

internee group from Latin America consisted of 156 six Japanese, 456 Germans, and 14 Italians arrived at the newly converted

INS camp in April 1942. This group was augmented by an additional 355 internees (chiefly of German nationality) who were

received in May, and by 253 Japanese internees in June. The population consisted primarily of adult males and a very small

number of teenage boys. In an effort to provide internees with activities, the camp had large athletic fields 600 feet long

by 450 feet wide and gardening areas outside the barbed-wire fence. Victory Huts were added to the existing CCC buildings

to afford the confinement site with accommodations for 1,200 internees, and a staff of 84 INS and civilian workers. However,

the camp’s population averaged closer to 600 internees per month. Through the remainder of 1942, and the beginning

of 1943, a portion of the detainees were repatriated, while others were reunited with their families at Crystal City (Family)

Internment Camp and Seagoville Enemy Alien Detention Station.

Kenedy Enemy Alien Detention Station main entrance (source: National Border Patrol Museum - El Paso)

By August 1944 Kenedy Enemy Alien Detention Station still held 525 internees; with the exception of 30,

all originated from Latin American countries. According to Protectorate Nations’ inspection visits, the majority of

internees desired repatriation to their home countries or return to the Latin American country from which they were taken

into custody.

Japanese Enemy Alien Art (Source: Judge Robert H. Thonhoff)

By 1942, the U.S. Army realized it needed to focus the efforts of it's Provost Marshal General's Office on the expected

task of guarding hundreds of thousands of Axis [Japan, German, and Italy] prisoners of war. In response, the DOJ gave the

INS increased authority to house potentially dangerous Enemy Aliens (including U.S. citizens) at internment camps throughout

the U.S. At this point in the war, the U.S. Military needed additional prisoner of war camp space, and the remaining internees

were transferred to other INS camps, paroled, or repatriated. The INS ceased operation of the facility in September 1944.

After the internment camp closed, the site became a German and later Japanese prisoner of war camp, each administered out

of Fort Sam Houston’s base prisoner of war camp.

Japanese,

German, & Italian Enemy Alien Internment

Kenedy

Enemy Alien Detention Station’s internee population volunteered or was “volunteered” for repatriation from

1942 until its closure in August 1944.

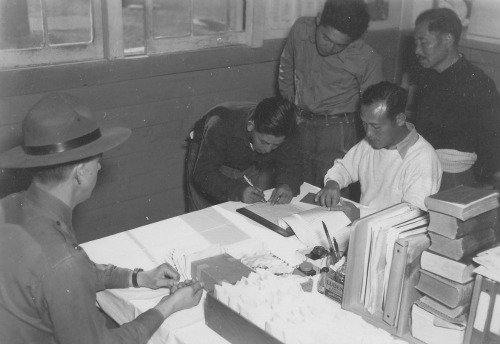

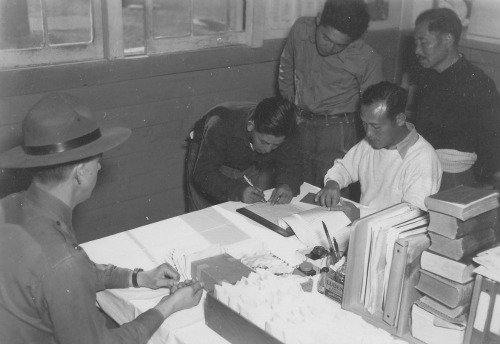

Japanese Latin Americans registering upon arrival at Kenedy (source: Judge Robert H. Thonhoff)

Oral History

Interviews

THC historians have conducted several oral history

interviews associated with Japanese, German, and Italian enemy alien internment at camps located in Texas. Most of these

interviews are with individuals who have links to Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp in Crystal City, Texas. More information

about this camp, and transcripts from those interviews, can be found here. We have one oral history interview related to Kenedy Enemy Alien Detention Station (see below for interview details

and transcript).

Please contact the THC Military History

Program Coordinator directly at militaryhistory@thc.texas.gov for all inquiries related to the agency's oral history collection.

Civilian employees at Kennedy

German American

(U.S. citizen) whose family escaped Nazi Germany during the 1930s and took up residence in Texas. During World War II, recently

graduated from Southern Methodist University, Marianne McCall worked at the Kenedy Enemy Alien Detention Station as an interpreter

and censor. McCall Transcript