|

At Least 250K Were Incinerated Alive It

is ironic that those who screech loudest about holocaust denial are 6 million times guiltier

of being in denial of confirmed holocausts. It is because Allied holocausts are so undisputed

that their only recourse is censorship ~ and denial. Across

Europe, especially in France, Germany, Italy and the Low Countries, thousands of cities and

their unfortunate civilian populations was fireball incinerated. Dresden and hundreds of other

cities and towns in Europe were literally turned into horrific crematories. Many metropolis never recovered from the Allied infernos. Whatever city and town landscapes you see in Germany today is alien to what it was in our lifetime. In respect of Dresden, the Federal Republic of Germany put the figure of dead at 35,000. This

is still not enough to fill any small city’s football arena. On February 14, 1945, the Saxon city’s

population, similar to that of say Liverpool, was teeming with refugees fleeing the ravishing

Red Army then being urged on by Winston Churchill. It is reasonable to assume that Dresden was host to 1,500,000 doomed

souls when the first of the RAF and USAAF carpet bombing raids commenced on St Valentine’s

Night 1945. Shortly after reunification, the Dresden city

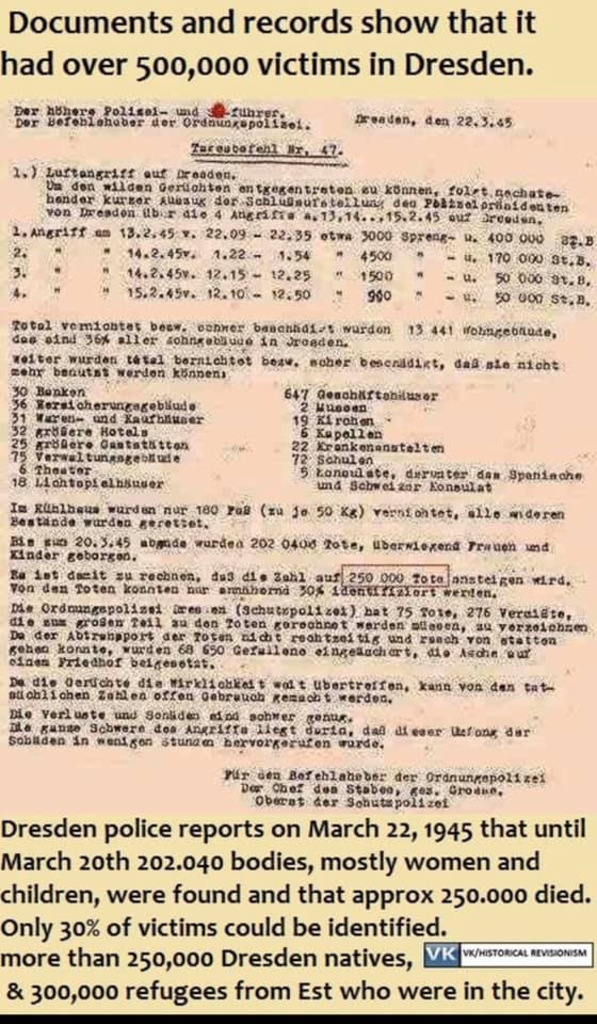

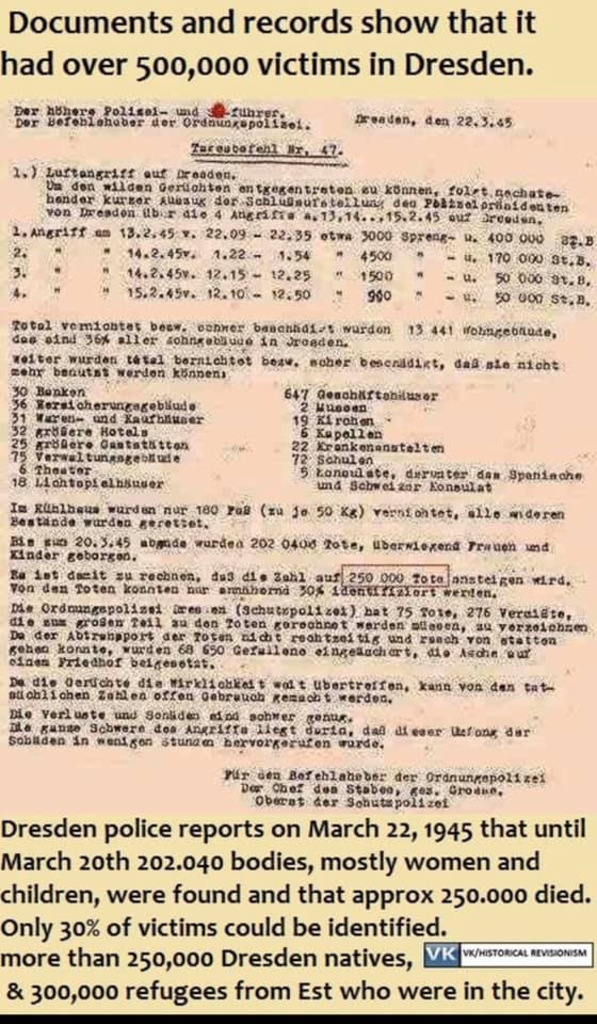

administration at that time also represented the survivors’ point of view. COMPACT

presents an original document of the Landeshauptstadt Dresden / Stadtverwaltung from July 31,

1992, signed by the Area Manager Karin Mitscherlich. It clearly states: In a vain attempt to provide more credible figures a document was eventually produced that appeared to concede that 202,000 people, mostly civilians had died in the Allied crematoria: ‘According to reliable information from the Dresden police, 202,040

dead, mostly women and children, were recovered by March 20, 1945. Only 30% of these

could be identified. Including the missing, a figure of 250,000 to 300,000 victims

is likely to be realistic. Appalling, many of the hillocks of corpses were later misrepresented by the Allied media as victims of German internment camps.’

However, scholarly revisionism has proved that this document was fake.

The false document was yet another vain attempt to sidestep the true figure of those incinerated, which could be set at four times that number who perished.

‘Dresden 1945’, has compiled a large number of sources in the chapter ‘Facts and Figures’ original documents, extracts from contemporary press releases, finds in Soviet encyclopaedias, plus testimonies from SED politicians, and in Issue published that

the overwhelming majority assume over 100,000 victims of the terrorist attack. An exact number is simply impossible because during the holocaust many of the victims

were burned to ashes or literally evaporated in their cellars. The ludicrous spin on the allied

spun casualty figures spurred historians on to further investigations: Corresponding new research

has not yet been completed. Concerned voices were raised

about the incineration not just of this great Saxon city but of the satanic-like scale of the

holocaust that was rained down on Germany, France, Italy and the Low Countries by the USAAF

and RAF. ‘One of the most unhealthy features of the bombing offensive was that the War Cabinet

– and in particular the Secretary for Air, Archibald Sinclair, felt it necessary

to repudiate publicly the orders which they themselves had given to Bomber Command.’ ~ R. H. S Crosman. Labour Minister of Housing. Sunday Telegraph, October 1 1961.

‘Kassel suffered over three-hundred air raids, some carrying waves of 1,000 bombers;

British by night, American by day. When on April, 4, 1945, Kassel surrendered,

of a population of 250,000, just 15,000 were left alive.’ ~

Jack Bell, Chicago Daily News Foreign Service, Kassel, May 15 1946. ‘Countless smaller towns and villages had been razed to the ground or turned into

ghost towns, like Wiener Neustadt in Austria, which emerged from the air raids and

the street fighting with only eighteen houses intact and its population reduced from

45,000 to 860.’ In the Ruins of the Reich, Douglas Botting. George, Allen

& Unwin. London. 1985. OTHER CITIES incinerated

with most of their populations: Berlin, Hamburg, Dortmund, Essen, Dresden, Frankfurt,

Nuremberg, Dusseldorf, Hanover, Bremen, Wuppertal, Vienna, Duisburg. Munich, Magdeburg, Leipzig,

Mannheim, Stuttgart, Kiel, Gelsdenkirchen, Bochum, Aachen, Wurzburg, Darmstadt, Krefeld, Munster,

Munchen Gladbach, Braunschweig, Ludwishafen, Remscheid, Pforzheim, Osnabruck, Mainz, Bielefeld, Gieben, Duren, Solingen, Wilhelmshaven, Karlsruhe, Oberhausen, Heilbronn,

Augsburg, Hamm, Knittelfeld, Luneburg, Cuxhaven, Kulmback, Hagen, Saarbrucken, Freiburg, Graz,

Koblenz, Ulm, Bonn, Bremerhaven, Wanne-Eickel, Worms, Lubeck, Schweinfurt, Kleve, Wiener Neustadt,

Wiesbaden, Paderborn, Bocholt, Hanau, Hildesheim, Emden, Siegen, Pirmasons, Hale, Bayreuth,

Kreuznach, Witten, Aschaffenburg, Kaiserlautern, Gladbeck, Dorsten, Innsbruck, Neumunster, Linz,

Klagenfurt, Reutlingen, Recklinghausen, Reuel, Regensburg, Homberg, Elmshorn, Wetzel, Villach, Hamelin, Konigsberg, Moers, Passau, Solbad Hall I. T, Coburg, Attnang-Puchheim,

Friedrichshafen, Frankfurt-Oder, Danzig, Bozen, Chemnitz, Rostock, Schwerte, Plauen, Rome,

Bad Kreuznach, Neapel, Genoa, Mailand, Turin. London Times reviewer on the British Official History of the Strategic Air Offensive: ‘One closes these volumes feeling, uneasily, that the true heroes of the story they tell are neither the contending air marshals, nor even the 58,888 officers and men of Bomber

Command who were killed in action . They

were the inhabitants of the German cities under attack; the men, women and children

who stoically endured and worked on among the flaming ruins of their homes and factories,

up till the moment when the allied armies overran them.’ ‘A sense of national embarrassment about the dark side of a virtuous war’

may be the explanation for the British Bombing Survey Unit’s silence. Such

a sentiment may account for the disdain in which ‘Bomber Harris’ was sometimes

later held. Perhaps it even explains the near silence about area bombing in the six-volume

war history by Winston Churchill.’ ~ Are We Beasts? Churchill and the

Moral Question of World War 11 ‘Area Bombing’ Christopher C. Harmon, Naval War College

Newport, Rhode Island. The U.S.

APOCALYPSE 1945

The Destruction of Dresden by David Irving Click on this link:

From 13 to 15 February 1945, British (and some American) heavy bombers

dropped 2,400 tons of high explosives and 1,500 tons of incendiary

bombs onto the ancient cathedral city of Dresden. In just a

few hours, around 250,000 to 350,000 civilians were blown up

or incinerated. (The Telegraph) Victor Gregg, a British para captured at Arnhem, was a prisoner of war in Dresden that night who was ordered to help with the clear up. In a 2014 BBC interview he recalled the hunt for survivors after the apocalyptic firestorm. In one incident, it took his team seven hours to get into a 1,000-person air-raid shelter in the Altstadt. Once inside, they found no survivors or corpses: just a green-brown liquid with bones sticking out of it. The cowering people had all melted. In areas further from the town centre there were legions of adults shrivelled to three feet in length. Children under the age of three had simply been vaporised. It was not the first time a German city had been

firebombed. “Operation Gomorrah” had seen Hamburg torched on 25 July

the previous year. Nine thousand tons of explosives and incendiaries had flattened

eight square miles of the city centre, and the resulting inferno had created

an oxygen vacuum that whipped up a 150-mile-an-hour wind burning at 800 Celsius.

The death toll was 37,000 people. (By comparison, the atom bomb in Nagasaki killed

40,000 on day one.) This thinking was not trumpeted from the rooftops.

But in November 1941 the Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command said he had been

intentionally bombing civilians for a year. “I mention this because, for

a long time, the Government, for excellent reasons, has preferred the world

to think that we still held some scruples and attacked only what the humanitarians

are pleased to call Military Targets. I can assure you, gentlemen, that we tolerate

no scruples.” The debate over this strategy of targeting civilians is still hotly contentious and emotional, in Britain and abroad. There is no doubting the bravery, sacrifice, and suffering of the young men who flew the extraordinarily dangerous missions: 55,573 out of Bomber Command’s 125,000 flyers never came home. The airmen even nicknamed their Commander-in-Chief

“Butcher” Harris, highlighting his scant regard for their survival. Supporters of Britain’s “area bombing”

(targeting civilians instead of military or industrial sites) maintain that it

was a vital part of the war. Churchill wrote that he wanted “absolutely devastating,

exterminating attacks by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland”.

In another letter he called it “terror bombing”. His aim was to demoralise the Germans to catalyse regime change. Research suggests that the soaring homelessness levels and family break ups did indeed depress civilian morale, but there is no evidence it helped anyone prise Hitler’s cold hand off the wheel. Others maintain that it was ghastly, but Hitler

started it so needed to be answered in a language he understood. Unfortunately,

records show that the first intentional “area bombing” of civilians

in the Second World War took place at Monchengladbach on 11 May 1940 at Churchill’s

orders (the day after he dramatically became prime minister), and four months

before the Luftwaffe began its Blitz of British cities.

Not everyone was convinced by city bombing. Numerous military and church leaders

voiced strong opposition. Freemason Dyson, now one of Britain’s most eminent

physicists, worked at Bomber Command from 1943-5. He said it eroded his moral

beliefs until he had no moral position at all. He wanted to write about it, but

then found the American novelist Kurt Vonnegut had said everything he wanted

to say. Like

Gregg, Vonnegut had been a prisoner in Dresden that night. He claimed that only one

person in the world derived any benefit from the slaughterhouse — him, because he wrote a famous book about it which pays him two or three dollars for every person killed. Germany’s bombing of British cities was

equally abhorrent. Germany dropped 35,000 tons on Britain over eight months in

1940-1 killing an estimated 39,000. (In total, the UK and US dropped around 1.9

million tons on Germany over 6 years.) Bombing German cities clearly did have an impact on the war. The question, though, is how much. The post-war US Bombing Survey estimated that the effect of all allied city bombing probably depleted the German economy by no more than 2.7 per cent. Allowing for differences

of opinion on the efficacy or necessity of “area bombing” in the days

when the war’s outcome remained uncertain (arguably until Stalingrad in February 1943), the key question on today’s anniversary remains whether the bombing of Dresden in February 1945 was militarily necessary — because by then the war was definitely over. Hitler was already in his bunker. The British and Americans were at the German border after winning D-Day the previous summer, while the Russians under Zhukov and Konev were well inside eastern Germany and racing pell-mell to Berlin. Dresden was a civilian town without military significance. It had

no material role of any sort to play in the closing months of the war. So, what

strategic purpose did burning its men, women, old people, and children serve?

Churchill himself later wrote that “the destruction of Dresden remains

a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing”. Seventy years on, fewer people ask precisely which military objective

justified the hell unleashed on Dresden. If there was no good strategic reason

for it, then not even the passage of time can make it right, and the questions

it poses remain as difficult as ever in a world in which civilians have continued

to suffer unspeakably in the wars of their autocratic leaders.   ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Click on this text to see what the "good guys' did to Dresden February 13th and 14th 1945...

. "On

13th February 1945 I was a navigator on one of the Lancaster bombers which devastated Dresden. I well remember the

briefing by our Group Captain. We were told that the Red Army was thrusting towards Dresden and that the town

would be crowded with refugees and that the center of the town would

be full of women and children. Our aiming point would be the market place.

I recall that

we were somewhat uneasy, but we did as we were told. We accordingly bombed

the target and on our

way back our wireless operator picked up a German broadcast accusing the RAF of terror tactics,

and that 65,000 civilians had died. We dismissed this as German propaganda.

The penny didn't

drop until a few weeks later when my squadron received a visit from the

Crown Film Unit who were

making the wartime propaganda films. There was a mock briefing, with one notable difference.

The same Group Captain now said, 'as the market place would be filled with women

and children on no account would we bomb the center of the town. Instead, our aiming

point would be a vital railway junction to the east.

I can categorically confirm that

the Dresden raid was a black mark on Britain's war record.

The aircrews on my squadron

were convinced that this wicked act was not instigated by our much-respected guvnor

'Butch' Harris but by Churchill. I have waited 29 years to say this, and it still worries

me."

...John Scudamore

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

[2001] TERROR BOMBING: THE CRIME OF THE TWENTIETH

CENTURY by Michael Walsh

. .

His full name was Walt Whitman Rostow. He fulfilled the hopes of his parents, Jewish immigrants from Russia, that he would grow up to be a successful American. During WWII he was

attached to the OFFICE OF STRATEGIC SERVICES (OSS), an intelligence

unit and precursor to the CIA, picking targets in Germany for American bombers to attack.

February 13th

and 14th, 1945 (two months prior to the German surrender) were the

dates chosen to firebomb Dresden, Germany after intense lobbying by Rostow.

February 14th, 1945 was the Christian

holy day known as "Ash Wednesday"... How clever to choose

Ash Wednesday to reduce a city over-populated by women, children and wounded to ashes. He went on to serve as Special Assistant for National

Security Affairs to President Lyndon Johnson in 1966–69.

We can curse his memory for his prominent role in the shaping of US foreign policy in Southeast Asia during the 1960s and fanning the flames of the Viet Nam War debacle.

Appropriately

Rostow died on February 13th, 2003

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Dresden

Was a Civilian Town With No Military Significance. Why Did We Burn Its People?

... Supporters of Britain's "area bombing"

(targeting civilians instead of military or industrial sites) maintain that it was a vital

part of the war. Churchill wrote that he wanted "absolutely devastating, exterminating attacks by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland". In another letter he called it "terror bombing".

... Others maintain that it was ghastly, but Hitler started it so needed to be answered

in a language he understood. Unfortunately, records show that the first intentional "area

bombing" of civilians in the Second World War took place at Monchengladbach on 11 May 1940 at Churchill's orders (the day after he dramatically became prime minister), and four months before the Luftwaffe began its Blitz of British cities. Remembering

Dresden

In the last months

of World War II, Allied bombers from the British Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force conducted several major bombing raids on the eastern

German city of Dresden. Beginning on the night of February 13, 1945, more than 1,200 heavy bombers dropped nearly 4,000 tons of high-explosive and incendiary

bombs on the city in four successive raids. An estimated 25,000 people were killed in the bombings and the firestorm that raged afterward. More than

75,000 dwellings were destroyed,

along with unique monuments of Baroque architecture in the historic city center. With photographs.

_____________________ How Many Germans Died under RAF Bombs at Dresden in 1945?

Introduction  The bombing of Dresden remains one of the deadliest and morally most-problematic raids of

World War II. Three factors make the bombing of Dresden unique: 1) a huge firestorm developed that engulfed much of the

city; 2) the firestorm engulfed a population swollen by refugees; and 3) defenses and shelters even for the original Dresden

population were minimal.[1] The result was a high death toll and the destruction of one of Europe’s most beautiful and cultural cities. The bombing of Dresden remains one of the deadliest and morally most-problematic raids of

World War II. Three factors make the bombing of Dresden unique: 1) a huge firestorm developed that engulfed much of the

city; 2) the firestorm engulfed a population swollen by refugees; and 3) defenses and shelters even for the original Dresden

population were minimal.[1] The result was a high death toll and the destruction of one of Europe’s most beautiful and cultural cities.

Many conflicting

estimates have been made concerning the number of deaths during the raids of Dresden on February 13-14, 1945. Historian

Richard J. Evans estimates that approximately 25,000 people died during these bombings.[2] Frederick Taylor estimates that from 25,000 to 40,000 people died as a result of the Dresden bombings.[3] A distinguished commission of German historians titled “Dresden Commission of Historians for the Ascertainment of

the Number of Victims of the Air Raids on the City of Dresden on 13/14 February 1945” estimates the likely death toll

in Dresden at around 18,000 and definitely not more than 25,000.[4] This later estimate is considered authoritative by many sources. While exact figures of deaths in the Dresden bombings can never

be obtained, some Revisionist historians estimate a death toll at Dresden as high as 250,000 people. Most establishment

historians state that a death toll at Dresden of 250,000 is an absolute impossibility. For example, Richard Evans states:

Even allowing for the unique circumstances of Dresden, a figure of 250,000 dead would have meant

that 20% to 30% of the population was killed, a figure so grossly out of proportion to other

comparable attacks as to have raised the eyebrows of anyone familiar with the statistics of

bombing raids…even if the population had been inflated by an influx of refugees fleeing

the advance of the Red Army.[5] Population of

Dresden

Historians generally agree that a large number of German refugees were in Dresden during

the night of February 13-14, 1945. However, the estimate of refugees in Dresden that

night varies widely. This is a major reason for the discrepancies in the death toll estimates

in the Dresden bombings.

Marshall De Bruhl states in his book Firestorm: Allied Airpower

and the Destruction of Dresden:

Nearly every apartment and house [in Dresden] was crammed with relatives

or friends from the east; many other residents had been ordered to take in strangers. There were makeshift campsites everywhere. Some 200,000 Silesians and East Prussians were

living in tents or shacks in the Grosser Garten. The city’s population was more than double

its prewar size. Some estimates have put the number as high as 1.4 million.

Unlike other major German cities, Dresden had an exceptionally low population density, due to

the large proportion of single houses surrounded by gardens. Even the built-up areas did not

have the congestion of Berlin and Munich. However, in February 1945, the open spaces, gardens,

and parks were filled with people. The Reich provided

rail transport from the east for hundreds of thousands of the fleeing easterners, but the last

train out of the city had run on February 12. Transport further west was scheduled to resume

in a few days; until then, the refugees were stranded in the Saxon capital.[6]

David Irving states in The Destruction of Dresden: Silesians represented probably 80% of the displaced

people crowding into Dresden on the night of the triple blow; the city which in peacetime had

a population of 630,000 citizens was by the eve of the air attack so crowded with Silesians,

East Prussians and Pomeranians from the Eastern Front, with Berliners and Rhinelanders from

the west, with Allied and Russian prisoners of war, with evacuated children’s settlement,

with forced laborers of many nationalities, that the increased population was now between 1,200,000 and 1,400,000 citizens, of whom, not surprisingly, several hundred thousand

had no proper home and of whom none could seek the protection of an air-raid shelter.[7]

A woman living on the outskirts of Dresden at the time of the bombings stated: “At the time my mother and I had train-station duty here in the city. The refugees! They all came from everywhere! The city was stuffed full!”[8]

Frederick Taylor states in his book Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945 that Dresden had been accepting refugees from the devastated cities of the Ruhr, and from Hamburg and Berlin, ever since the British bombing campaign began in earnest. By late 1943 Dresden was already overstretched and finding it hard to accept more outsiders. By the winter of 1944-1945, hundreds of thousands of German refugees were traveling from the east in an attempt to escape the Russian army.[9]

The German government regarded the acceptance of Germans from the east as an essential

duty. Der Freiheitskampf, the official German organ for Saxony, urged citizens to offer temporary accommodation:

There is still room everywhere. No family should remain without guests!

Whether or not your habits of life are compatible, whether the coziness of your domestic situation is disturbed, none of these things should matter! At our doors stand people who for the moment

have no home—not even to mention the loss of their possessions.[10]

However, Taylor states that it was general policy in Dresden to have refugees on their way to the west to continue onwards within 24 hours. Fleeing the Russians was not a valid justification for seeking and maintaining residence in Dresden. Taylor states that the best estimate by Götz Bergander, who spent time on fire-watching duties and on refugee-relief work in Dresden, was that approximately 200,000 nonresidents were in Dresden on the night of February 13-14, 1945. Many of these refugees would have been living

in quarters away from the targeted center of Dresden.[11]

The Dresden historian Friedrich Reichert estimates that only 567,000 residents and

100,000 refugees were in Dresden on the night of the bombings. Reichert quotes witnesses who state that no refugees were billeted in Dresden houses and that no billeting took place in Dresden’s parks or squares. Thus, Reichert estimates that the number of people in Dresden on the night of the bombings was not much greater than the official figure of Dresden’s population before the war.[12]

Reichert’s estimate of Dresden’s population during the bombings is almost

certainly too low. As a RAF memo analyzed it before the attack: Dresden, the seventh largest city in Germany

and not much smaller than Manchester is also [by] far the largest unbombed built-up area the

enemy has got. In the midst of winter with refugees pouring westwards and troops to be rested,

roofs are at a premium, not only to give shelter to workers, refugees and troops alike, but

also to house the administrative services displaced from other areas…[13]

Alexander McKee states in regard to Dresden:

Every household had its large quota of refugees, and many more had arrived

in Dresden that day, so that the pavements were blocked by them, as they struggled onwards or simply sat exhausted on their suitcases and rucksacks. For these reasons, no one has

been able to put a positive figure to the numbers of the dead, and no doubt no one ever will.[14]

The report prepared by the USAF Historical Division Research Studies Institute Air University states that “there may probably have been about 1,000,000 people in Dresden on the night of the 13/14 February RAF attack.”[15] I think the 1 million population figure cited in this report constitutes a

realistic and conservative minimum estimate of Dresden’s population during the

Allied bombings of February 13-14, 1945. Did Only 25,000 People Die? If the 25,000 death-toll estimate in Dresden is accurate, we

are left with the odd result that Allied air power, employed for textbook purposes

to its full measure and with no restrictions, over an especially vulnerable large

city near the end of the war, when Allied air superiority was absolute and German

defenses nearly nonexistent, was less effective than Allied air power had been

in previous more-difficult operations such as Hamburg or Berlin. I think the

extensive ruins left in Dresden suggest a degree of complete destruction not seen

before in Germany[NJP1] .

The Dresden bombings created a massive firestorm of epic proportions, and were in no way

a failed mission with only a fraction of the intended results. The fires from the first raid alone had been visible more than 100 miles from Dresden.[16] The Dresden raid was the perfect execution of the Bomber Command theory of

the double blow: two waves of bombers, three hours apart, followed the next day

by a massive daylight raid by more bombers and escort fighters. Only a handful

of raids ever actually conformed to this double-strike theory, and those that

did were cataclysmic.[17]

Dresden also lacked an effective network of air-raid shelters to protect its inhabitants. Hitler had ordered that over 3,000 air-raid bunkers be built in 80 German towns and cities. However, not one was built in Dresden because the city was not regarded as being in danger of air attack. Instead, the civil air defense in Dresden devoted most of its efforts to creating tunnels between the cellars of the housing blocks so that people could escape from one building to another. These tunnels exacerbated the effects of the Dresden firestorm by channeling smoke and fumes from one basement to the next and sucking out the oxygen from a network of interconnected cellars.[18]

The vast majority of the population of Dresden did not have access to proper air-raid

shelters. When the British RAF attacked Dresden that night, all the residents and refugees in Dresden could do was take refuge in their cellars. These cellars proved to be death traps in many cases. People who managed to escape from their cellars were often sucked into the firestorm as they struggled to flee the city.[19]

Dresden was all but defenseless against air attack, and the people of Dresden suffered the consequences. The bombers in the Dresden raids were able to conduct their attacks relatively free from fear of harassment by German defenses. The master bombers ordered the bombers to descend to lower levels, and the crews felt confident to do so and to maintain a steady altitude and heading during the bombing runs. This ensured that the Dresden raids were particularly concentrated and thus particularly effective.[20] The RAF conducted a technically perfect fire-raising attack on Dresden.[21]

The British were fully aware that mass death and destruction could result from the bombing

of Germany’s cities. The Directorate of Bombing Operations predicted the following consequences from Operation Thunderclap:

If we assume that the daytime population of the area attacked is 300,000,

we may expect 220,000 casualties. Fifty per cent of these or 110,000 may expect to be killed. It is suggested that such an attack resulting in so many deaths, the great proportion

of which will be key personnel, cannot help but have a shattering effect on political and civilian

morale all over Germany.”[22]

The destruction of Dresden was so complete that major companies were reporting fewer

than 50% of their workforce present two weeks after the raids.[23] By the end of February 1945, only 369,000 inhabitants remained in the city.

Dresden was subject to further American attacks by 406 B-17s on March 2 and 580

B-17s on April 17, leaving an additional 453 dead.[24] Comparison to Pforzheim

Bombing

A raid that closely resembles that of Dresden occurred 10 days later on February 23, 1945 at Pforzheim. Since neither Dresden nor Pforzheim had suffered much damage earlier in the war, the flammability of both cities had been preserved.[25] A perfect firestorm was created in both of these defenseless cities. These

cities also lacked sufficient air-raid shelters for their citizens.

The area of destruction at Pforzheim comprised approximately

83% of the city, and 20,277 out of 65,000 people died according to official

estimates.[26] Sönke Neitzel also estimates that approximately 20,000 out of a total population

of 65,000 died in the raid at Pforzheim.[27] This means that over 30% of the residents of Pforzheim died in one bombing attack. The question

is: If more than 30% of the residents of Pforzheim died in one bombing attack,

why would only approximately 2.5% of Dresdeners die in similar raids 10 days earlier?

The second wave of bombers in the Dresden raid appeared over Dresden at the very time

that the maximum number of fire brigades and rescue teams were in the streets of the burning city. This second wave of bombers compounded the earlier destruction many times, and by design killed the firemen and rescue workers so that the destruction in Dresden could rage on unchecked.[28] The raid on Pforzheim, by contrast, consisted of only one bombing attack. Also,

Pforzheim was a much smaller target, so that it would have been easier for the

people on the ground to escape from the blaze. The only reason why the death-rate percentage would be higher at Pforzheim versus

Dresden is that a higher percentage of Pforzheim was destroyed in the bombings.

Alan Russell estimates that 83% of Pforzheim’s city center was destroyed

versus only 59% of Dresden’s.[29] This would, however, account for only a portion of the percentage difference

in the death tolls. Based on the death toll in the Pforzheim raid, it is reasonable

to assume that a minimum of 20% of Dresdeners died in the British and American

attacks on the city. The 2.5% death rate figure of Dresdeners estimated by establishment

historians is an unrealistically low figure. If a 20% death rate figure times an estimated population in Dresden of 1 million

is used, the death-toll figure in Dresden would be 200,000. If a 25% death-rate

figure times an estimated population of 1.2 million is used, the death toll figure

in Dresden would be 300,000. Thus, death-toll estimates in Dresden of 250,000

people are quite plausible when compared to the Pforzheim bombing. How Were the Dead Disposed Of?

Historian Richard Evans asks:

And how was it imaginable that 200,000 bodies could have been recovered

from out of the ruins in less than a month? It would have required a veritable army of people to undertake such work, and hundreds of sorely needed vehicles to transport the bodies. The

effort actually undertaken to recover bodies was considerable, but there was no evidence that

it reached the levels required to remove this number.[30]

Richard Evans does not recognize that the incineration of corpses on the Dresden market square, the Altmarkt, was not the only means of disposing of bodies at Dresden. A British sergeant reported on the disposal of bodies at Dresden:

They had to pitchfork shriveled

bodies onto trucks and wagons and cart them to shallow graves on the outskirts of the city.

But after two weeks of work the job became too much to cope with and they found other means

to gather up the dead. They burned bodies in a great heap in the center of the city, but the

most effective way, for sanitary reasons, was to take flamethrowers and burn the dead as they

lay in the ruins. They would just turn the flamethrowers into the houses, burn the dead and

then close off the entire area. The whole city is flattened. They were unable to clean up the

dead lying beside roads for several weeks.[31]

Historians also differ on whether or not large numbers of bodies in Dresden were so incinerated

in the bombing that they could no longer be recognized as bodies. Frederick Taylor

mentions Walter Weidauer, the high burgomaster of Dresden in the postwar period, as stating [T]here is no substance

to the reports that tens of thousands of victims were so thoroughly incinerated that no individual

traces could be found. Not all were identified, but—especially as most victims died of

asphyxiation or physical injuries—the overwhelming majority of individuals’ bodies

could at least be distinguished as such.”[32]

Other historians cite evidence that bodies were incinerated beyond recognition. Alexander

McKee quotes Hildegarde Prasse on what she saw at the Altmarkt after the Dresden

bombings:

What I saw at the Altmarkt was cruel. I could not believe my eyes. A few of the men who had

been left over [from the Front] were busy shoveling corpse after corpse on top of the other.

Some were completely carbonized and buried in this pyre, but nevertheless they were all burnt

here because of the danger of an epidemic. In any case, what was left of them was hardly recognizable.

They were buried later in a mass grave on the Dresdner Heide.[33]

Marshall De Bruhl cites a report found in an urn by a gravedigger in 1975 written on March

12, 1945, by a young soldier identified only as Gottfried. This report states: I saw the most painful

scene ever….Several persons were near the entrance, others at the flight of steps and

many others further back in the cellar. The shapes suggested human corpses. The body structure

was recognizable and the shape of the skulls, but they had no clothes. Eyes and hair carbonized

but not shrunk. When touched, they disintegrated into ashes, totally, no skeleton or separate

bones. I recognized a male corpse as

that of my father. His arm had been jammed between two stones, where shreds of his grey suit

remained. What sat not far from him was no doubt mother. The slim build and shape of the head

left no doubt. I found a tin and put their ashes in it. Never had I been so sad, so alone and

full of despair. Carrying my treasure and crying I left the gruesome scene. I was trembling

all over and my heart threatened to burst. My helpers stood there, mute under the impact.[34]

The incineration of large numbers of people in Dresden is also indicated by estimates of the extreme temperature reached in Dresden during the firestorm. While no survivor has ever reported the actual temperature reached during the Dresden firestorm, many historians estimate that temperatures reached 1,500° Centigrade (2,732° Fahrenheit).[35] Since temperatures in a cremation chamber normally reach only 1,400 degrees to

1,800 degrees Fahrenheit[36], large numbers of people in Dresden would have been incinerated from the extreme

heat generated in the firestorm. Historians also differ on whether or not bodies are still being recovered in Dresden.

For example, Frederick Taylor states: “Since 1989—even with the extensive

excavation and rebuilding that followed the fall of communism in Dresden—no

bodies have been recovered at all, even though careful archaeological investigations

have accompanied the redevelopment.”[37]

Marshall De Bruhl does not agree with Taylor’s statement. De Bruhl notes that numerous other skeletons of victims were discovered in the ruins of Dresden as rubble was removed or foundations for new buildings were dug. De Bruhl states: One particularly poignant

discovery was made when the ruins adjacent to the Altmarkt were being excavated in the 1990s.

The workmen found the skeletons of a dozen young women who had been recruited from the countryside

to come into Dresden and help run the trams during the war. They had taken shelter from the

rain of bombs in an ancient vaulted subbasement, where their remains lay undisturbed for almost

50 years.[38] Conclusion The destruction

from the Dresden bombings was so massive that exact figures of deaths will never

be obtainable. However, the statement from the Dresden Commission of Historians

that “definitely no more than 25,000” died in the Dresden bombings is probably inaccurate. An objective analysis of the evidence indicates that almost certainly far more than 25,000 people died from the bombings of Dresden. Based on a comparison to the Pforzheim bombing and the other similar bombing attacks, a death toll in Dresden of 250,000 people is easily possible.

ENDNOTES [1] McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 275.

[2] Evans, Richard J., Lying about Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial, New York: Basic Books, 2001,

p. 177. [3] Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, p. 354.

[4] http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/death-toll-debate-how-many-died-in-the-bombing-of-dresden-a-581992.html.

[5] Evans, Richard J., Lying about Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial, New York: Basic Books, 2001,

p. 158. [6] DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006,

p. 200. [7] Irving, David, The Destruction of Dresden, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964, p. 98.

[8] Ten Dyke, Elizabeth A., Dresden: Paradoxes of Memory in History, London and New York: Routledge, 2001, p. 82.

[9] Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, pp. 134, 227-228.

[11] Ibid., pp. 229, 232. [12] Evans, Richard J., Lying about Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial, New York: Basic Books, 2001,

p. 174. [13] Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, pp. 3, 406. See also River,

Charles Editors, The Firebombing of Dresden: The History and Legacy of the Allies’ Most Controversial Attack on

Germany, Introduction, p. 2. [14] McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 177.

[15] http://glossaryhesperado.blogspot.com/2008/04/facts-about-dresden-bombings.html. [16] Cox, Sebastian, “The Dresden Raids: Why and How,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm:

The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, pp. 44, 46. [17] DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006,

pp. 204-205. [18] Neitzel, Sönke, “The City under Attack,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The

Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, pp. 68-69. [19] Ibid., pp. 69, 72, 76. [20] Cox, Sebastian, “The Dresden Raids: Why and How,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm:

The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, pp. 52-53. [21] Davis, Richard G., Carl A. Spaatz and the Air War in Europe, Washington, D.C.: Center for Air Force History, 1993,

p. 557. [22] Hastings, Max, Bomber Command, New York: The Dial Press, 1979, pp. 347-348.

[23] Cox, Sebastian, “The Dresden Raids: Why and How,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm:

The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, p. 57. [24] Overy, Richard, The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied Air War over Europe, 1940-1945, New York: Viking Penguin, 2014,

p. 314. [25] Friedrich, Jörg, The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, New York, Columbia University Press, 2006, p. 94.

[26] Ibid., p. 91. See also DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden,

New York: Random House, Inc., 2006, p. 255. [27] Neitzel, Sönke, “The City under Attack,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The

Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, p. 77. [28] DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006,

p. 210. See also McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984,

p. 112. [29] Russell, Alan, “Why Dresden Matters,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The Bombing

of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, p. 162. [30] Evans, Richard J., Lying About Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial, New York: Basic Books, 2001,

p. 158. [31] Regan, Dan, Stars and Stripes London edition, Saturday, May 5, 1945, Vol. 5, No. 156.

[32] Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, p. 448.

[33] McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 248.

[34] DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006,

pp. 253-254. [35] Alexander McKee cites estimates of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox,

New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 176). [36] http://nfda.org/planning-a-funeral/cremation/160.html#hot. [37] Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, p. 448.

[38] DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006,

p. 254.

The Blood of Dresden Following is an extract from Armageddon

in Retrospect by Kurt Vonnegut in which

he describes the scenes of ‘obscene brutality’ he witnessed as a prisoner of war in Dresden which inspired his classic novel Slaughterhouse-Five. Dresden before the allied bombing It was a routine speech we got during our first day of basic training,

delivered by a wiry little lieutenant: “Men, up to now you’ve been

good, clean, American boys with an American’s love for sportsmanship and

fair play. We’re here to change that. “Our job is to make you the meanest, dirtiest bunch of scrappers in the history of the world. From now on, you can forget the Marquess of Queensberry rules and every other set of rules. Anything and everything goes.

“Never hit a man above the belt when you can kick him below it. Make the bastard scream. Kill him any way you can. Kill, kill, kill – do you understand?” His talk was greeted with nervous laughter

and general agreement that he was right. “Didn’t Hitler and Tojo

say the Americans were a bunch of softies? Ha! They’ll find out.” And of course, Germany and Japan did find out: a toughened-up democracy

poured forth a scalding fury that could not be stopped. It was a war of reason

against barbarism, supposedly, with the issues at stake on such a high plane

that most of our feverish fighters had no idea why they were fighting –

other than that the enemy was a bunch of bastards. A new kind of war, with all

destruction, all killing approved. A

lot of people relished the idea of total war: it had a modern ring to it, in keeping with

our spectacular technology. To them it was like a football game. [Back home in America], three small-town merchants’ wives, middle-aged and plump, gave

me a ride when I was hitchhiking home from Camp Atterbury. “Did you kill

a lot of them Germans?” asked the driver, making cheerful small-talk. I

told her I didn’t know. This

was taken for modesty. As I was getting out of the car, one of the ladies patted me

on the shoulder in motherly fashion: “I’ll bet you’d like to get over and kill some of them dirty Japs now, wouldn’t you?”

We exchanged knowing winks. I didn’t tell those simple souls that I had been

captured after a week at the front; and more to the point, what I knew and thought

about killing dirty Germans, about total war. The reason for my being sick at

heart then and now has to do with an incident that received cursory treatment

in the American newspapers. In February 1945, Dresden, Germany, was destroyed,

and with it over 100,000 human beings. I was there. Not many know how tough America

got. I was among a group of

150 infantry privates, captured in the Bulge breakthrough and put to work in

Dresden. Dresden, we were told, was the only major German city to have escaped

bombing so far. That was in January 1945. She owed her good fortune to her unwarlike

countenance: hospitals, breweries, food-processing plants, surgical supply houses,

ceramics, musical instrument factories and the like. Since the war [had started], hospitals had become her prime concern. Every day hundreds of wounded came into the tranquil sanctuary from the east and west. At night, we would hear the dull rumble of distant air raids. “Chemnitz is getting it tonight,” we used to say, and speculated

what it might be like to be the bright young men with their dials and cross-hairs. “Thank heaven we’re in an ‘open

city’,” we thought, and so thought the thousands of refugees –

women, children and old men who came in a forlorn stream from the smouldering

wreckage of Berlin, Leipzig, Breslau, Munich. They flooded the city to twice its normal population. There was no war in Dresden. True, planes came over nearly every day and

the sirens wailed, but the planes were always en route elsewhere. The alarms

furnished a relief period in a tedious work day, a social event, a chance to

gossip in the shelters. The shelters, in fact, were not much more than a gesture,

casual recognition of the national emergency: wine cellars and basements with

benches in them and sandbags blocking the windows, for the most part. There were a few more adequate bunkers in the centre of the city, close to the government offices, but nothing like the staunch subterranean fortress that rendered Berlin impervious to her daily pounding. Dresden had no reason to prepare for attack – and thereby hangs a beastly tale. Dresden was surely among the world’s most lovely cities. Her streets

were broad, lined with shade-trees. She was sprinkled with countless little

parks and statuary. She had marvellous old churches, libraries, museums, theatres,

art galleries, beer gardens, a zoo and a renowned university. It was at one time a tourist’s paradise. They would be far better

informed on the city’s delights than am I. But the impression I have is

that in Dresden – in the physical city – were the symbols of the

good life; pleasant, honest, intelligent. In the swastika’s shadow, those

symbols of the dignity and hope of mankind stood waiting, monuments to truth. The accumulated treasure of hundreds of years, Dresden spoke eloquently of those things excellent in European civilisa-tion wherein our debt lies deep. I was a prisoner, hungry, dirty and full of hate for our captors, but I loved that city and saw the blessed wonder of her past and the rich promise of her future. In February 1945, American bombers reduced this treasure to crushed stone

and embers; disembowelled her with high explosives and cremated her with incendiaries. The atom bomb may represent a fabulous advance,

but it is interesting to note that primitive TNT and thermite managed to exterminate

in one bloody night more people than died in the whole London blitz. Fortress

Dresden fired a dozen shots at our airmen. Once back at their bases and sipping

hot coffee, they probably remarked: “Flak unusually light tonight. Well,

guess it’s time to turn in.” Captured British pilots from tactical fighter units (covering frontline troops) used to chide those who had flown heavy bombers on city raids with: “How on earth did you stand the stink of boiling urine and burning perambulators?” A perfectly routine piece of news: “Last night our planes attacked

Dresden. All planes returned safely.” The only good German is a dead one:

over 100,000 evil men, women, and children (the able-bodied were at the fronts)

forever purged of their sins against humanity. By chance, I met a bombardier

who had taken part in the attack. “We hated to do it,” he told me. The night they came over, we spent in an underground meat locker in a slaughterhouse.

We were lucky, for it was the best shelter in town. Giants stalked the earth

above us. First came the soft murmur of their dancing on the outskirts, then

the grumbling of their plodding towards us, and finally the ear-splitting crashes

of their heels upon us – and thence to the outskirts again. Back and forth

they swept: saturation bombing. “I

screamed and I wept and I clawed the walls of our shelter,” an old lady told me. “I prayed to God to ‘please, please, please, dear God, stop them’. But he didn’t hear me. No power could stop them. On they came, wave after wave. There was no way we could surrender; no way to tell them we couldn’t stand it any more. There was nothing anyone could do but sit and wait for morning.” Her daughter and grandson were killed. Our little prison was burnt to the ground.

We were to be evacuated to an outlying camp occupied by South African prisoners.

Our guards were a melancholy lot, aged Volkssturmers and disabled veterans. Most

of them were Dresden residents and had friends and families somewhere in the

holocaust. A corporal, who had lost an eye after two years on the Russian front,

ascertained before we marched that his wife, his two children and both of his

parents had been killed. He had one cigarette. He shared it with me.

Dresden after the allied bombing Our march to new quarters took us to the city’s edge. It was impossible

to believe that anyone had survived in its heart. Ordinarily, the day would have

been cold, but occasional gusts from the colossal inferno made us sweat. And

ordinarily, the day would have been clear and bright, but an opaque and towering

cloud turned noon to twilight. A

grim procession clogged the outbound highways; people with blackened faces streaked with

tears, some bearing wounded, some bearing dead. They gathered in the fields. No

one spoke. A few with Red Cross armbands did what they could for the casualties. Settled with the South Africans, we enjoyed a week without work. At the

end of it, communications were reestablished with higher headquarters and we

were ordered to hike seven miles to the area hardest hit. Nothing in the district had escaped the fury. A city of jagged building

shells, of splintered statuary and shattered trees; every vehicle stopped, gnarled

and burnt, left to rust or rot in the path of the frenzied might. The only sounds

other than our own were those of falling plaster and their echoes.

I cannot describe the desolation properly, but I can give an idea of how it made

us feel, in the words of a delirious British soldier in a makeshift POW hospital:

“It’s frightenin’, I tell you. I would walk down one of them

bloody streets and feel a thousand eyes on the back of me ’ead. I would

’ear ’em whis-perin’ behind me. I would turn around to look at ’em and there wouldn’t be a bloomin’ soul in sight. You can feel ’em and you can ’ear ’em but there’s never anybody there.” We knew what he said was so. For “salvage” work, we were divided into small crews, each under

a guard. Our ghoulish mission was to search for bodies. It was rich hunting

that day and the many thereafter. We started on a small scale – here a

leg, there an arm, and an occasional baby – but struck a mother lode before

noon. We cut our way through

a basement wall to discover a reeking hash of over 100 human beings. Flame must

have swept through before the building’s collapse sealed the exits, because

the flesh of those within resembled the texture of prunes. Our job, it was explained, was to wade into the shambles and bring forth the remains. Encouraged by cuffing and guttural abuse, wade in we did. We did exactly that, for the floor was covered with an unsavoury broth from burst water mains and viscera. A number of victims, not killed outright, had attempted to escape through a narrow emergency exit. At any rate, there were several bodies packed tightly into the passageway. Their leader had made it halfway up the steps before he was buried up to his neck in falling brick and

plaster. He was about 15, I think. It is with some regret that I here besmirch the nobility of our airmen,

but, boys, you killed an appalling lot of women and children. The shelter I have

described and innumerable others like it were filled with them. We had to exhume

their bodies and carry them to mass funeral pyres in the parks, so I know. The funeral pyre technique was abandoned

when it became apparent how great was the toll. There was not enough labour to

do it nicely, so a man with a flamethrower was sent down instead, and he cremated

them where they lay. Burnt alive, suffocated, crushed – men, women, and

children indiscriminately killed.

For all

the sublimity of the cause for which we fought, we surely created a Belsen of our own. The method was impersonal, but the result was equally cruel and heartless. That, I am afraid, is a sickening truth. When we had become used to the darkness, the odour and the carnage, we began musing as to what each of the corpses had been in life. It was a sordid game: “Rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief . . .” Some had fat purses and jewellery, others had precious foodstuffs. A boy had his dog still leashed to him.

Renegade Ukrainians in German uniform were in charge of our operations in the shelters

proper. They were roaring drunk from adjacent wine cellars and seemed to enjoy

their job hugely. It was a profitable one, for they stripped each body of valuables

before we carried it to the street. Death became so commonplace that we could

joke about our dismal burdens and cast them about like so much garbage. Not so with the first of them, especially

the young: we had lifted them on to the stretchers with care, laying them out

with some semblance of funeral dignity in their last resting place before the

pyre. But our awed and sorrowful propriety gave way, as I said, to rank callousness.

At the end of a grisly day, we would smoke and survey the impressive heap of dead accumulated. One of us flipped his cigarette butt into the pile: “Hell’s bells,” he said, “I’m

ready for Death any time he wants to come after me.”

A few

days after the raid, the sirens screamed again. The listless and heartsick survivors were

showered this time with leaflets. I lost my copy of the epic, but remember that it

ran something like this: “To the people of Dresden: we were forced to bomb your city because of the heavy military traffic your railroad facilities have been carrying. We realise that we haven’t always hit our objectives. Destruction of anything other than military objectives was unintentional, unavoidable fortunes of war.” That explained the slaughter to everyone’s satisfaction, I am sure,

but it aroused no little contempt. It is a fact that 48 hours after the last

B-17 had droned west for a well-earned rest, labour battalions had swarmed over

the damaged rail yards and restored them to nearly normal service. None of the

rail bridges over the Elbe was knocked out of commission. Bomb-sight manufacturers

should blush to know that their marvellous devices laid bombs down as much as

three miles wide of what the military claimed to be aiming for. The leaflet should have said: “We hit every blessed church, hospital, school, museum, theatre, your university, the zoo, and every apartment building in town, but we honestly weren’t trying hard to do it. C’est la guerre. So sorry. Besides, saturation bombing

is all the rage these days, you know.” There was tactical significance: stop the railroads. An excellent manoeuvre,

no doubt, but the technique was horrible. The planes started kicking high explosives

and incendiaries through their bomb-bays at the city limits, and for all the

pattern their hits presented, they must have been briefed by a Ouija board. Tabulate the loss against the gain. Over

100,000 noncombatants and a magnificent city destroyed by bombs dropped wide

of the stated objectives: the railroads were knocked out for roughly two days.

The Germans counted it the greatest loss of life suffered in any single raid.

The death of Dresden was a bitter tragedy, needlessly and wilfully executed. The

killing of children – “Jerry” children or “Jap” children, or whatever enemies the future may hold for us – can never be justified.

The facile reply to great groans such as mine is the most hateful of all clichés, “fortunes of war”, and another: “They asked for it. All they understand

is force.” Who asked for

it? The only thing who understands is force? Believe me, it is not easy to

rationalise the stamping out of vineyards where the grapes of wrath are stored when

gathering up babies in bushel baskets or helping a man dig where he thinks his wife

may be buried. Certainly, enemy

military and industrial installations should have been blown flat, and woe unto

those foolish enough to seek shelter near them. But the “Get Tough America” policy, the spirit of revenge, the approbation of all destruction and killing, have earned us a name for obscene brutality. Our

leaders had a carte blanche as to what they might or might not destroy. Their mission

was to win the war as quickly as possible; and while they were admirably trained to do just that, their decisions on the fate of certain priceless world heirlooms – in one case, Dresden – were not always judicious. When, late in the war, with the Wehrmacht breaking up on all fronts, our planes were sent to destroy this last major city, I doubt if the question was asked: “How will this tragedy benefit us, and how will that benefit compare with

the ill-effects in the long run?” Dresden, a beautiful city, built in the art spirit, symbol of an admirable

heritage, so anti-Nazi that Hitler visited it but twice during his whole reign,

food and hospital centre so bitterly needed now – ploughed under and salt

strewn in the furrows. World

war two was fought for near-holy motives. But I stand convinced that the brand of justice

in which we dealt, wholesale bombings of civilian populations, was blasphemous. That

the enemy did it first has nothing to do with the moral problem. What I saw of our air war, as the European conflict neared an end, had the earmarks of being an irrational war for war’s sake. Soft citizens of the American democracy had learnt to kick a man below the belt and make the bastard scream. The occupying Russians, when they discovered that we were Americans, embraced us and congratulated us on the complete desolation our planes had wrought. We accepted their congratulations with good grace and proper modesty, but I felt then as I feel now, that I would have given my life to save Dresden for the world’s generations to come.

That is how everyone should feel about every city on earth. © Kurt Vonnegut Jr Trust 2008 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Dresden 1945: The Devil's Tinderbox - Dresden 1945: The Devil's Tinderbox,by Alexander McKee.

New York:

- E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1982, 1984, with maps, photographs, index.

Reviewed by Charles Lutton The destruction of the virtually undefended German

city of Dresden by bombers of the Royal Air Force and U.S. Army Air Force, in

mid-February, 1945, remains one of the most controversial episodes of the Second

World War. In 1963, British historian David Irving published a pathbreaking study

on this topic. Another widely-published British military historian, Alexander

McKee, has produced a new account of the Dresden bombing, based in part upon

an examination of official records recently declassified, as well as interviews

from survivors of the attack and Allied airmen who flew in the raids. McKee had doubts about the efficacy of area bombing when, as a soldier

with the 1st Canadian Army, he witnessed the results of the Allied bombing of

"friendly" French towns. Following visits to the cities of Caen and

Lisieux, he wrote in his personal war diary: "Lisieux and Caen are examples of the inflexibility of the four-motor heavy bombers: it cannot block a road without bringing down a city. I'm not surprised that our troops advancing between Caen and Lisiel=c were fired on by French civilians. No doubt many Frenchmen found it hard to be liberated by a people who seem, by their actions, to specialise in the mass murder of their friends." McKee was an eye-witness to the final destruction

of the towns of Emmerich and Arnhem. He related that, "In Emmerich I saw

no building whatever intact .... This process, when the town was an Allied one,

we referred to with bitter mockery as 'Liberation.' When you said that such-and-such

a place had been 'liberated,' you meant that hardly one stone still stood upon

another." The bombing of urban areas which might contain targets of military importance was a policy advocated by leading British air strategists long before the outbreak of the war. McKee reviewed the writings of the air power theorists of the 1920s and 30s, observing that "retreading them now is like browsing through a British Mein Kampf. The horror to come is all there between the lines. What they are really advocating is an all-out attack on non-combatants, men, women, and children, as a deliberate policy of terror?" After sifting through the evidence, the author

refers to these proferred justifications as the "standard white-wash gambit."

There was a military barracks in Dresden, but it was located on the out skirts

of the "New Town," miles away from the selected target area. There

were some hutted camps in the city-full of starving refugees who had fled from the

advancing Red Terror in the East. The main road route passed on the west outside the

city limits. The railway network led to an important junction, but this, too, passed outside the center of the "Old City," which was the focal point for the bombing attacks. No railway stations were on the British target maps, nor, apparently, were bridges, the destruction of which could have impeded German communications with the Eastern Front. And despite the claims of U.S. Air Force historians, writing in 1978, that "The Secretary of War had

to be appraised of ... the Russian request for its neutralization," the

author has unearthed no evidence of such a Soviet request. What the author has discovered about the attack

is that: - By the end

of Summer, 1944, "there is evidence that the Western Allies were contemplating

- some

terrible but swift end to the war by committing an atrocity which would terrify the

- enemy

into instant surrender. Without doubt, the inner truth has still to be prised loose,

- but

the thread of thought can be discerned."

- "The

bomber commanders were not really interested in any purely military or economic

- targets ....

What they were looking for was a big built-up area which they could burn ....

- The attraction

Dresden had for Bomber Command was that the centre

- of the city should burn easily and

magnificentlv: as indeed it was to do."

- At the time

of the attacks on February 13-14, 1945, the inhabitants of Dresden were

- mostly women

and children, many of whom had just arrived as refugees from the East.

- There were also

large numbers of Allied POWs. Few German males of military age

- were left in the city

environs. The author cites the official Bomber Command history

- prepared by Sir Charles

Webster and Dr. Noble Frankland, which reveals that "the

- unfortunate, frozen, starving

civilian refugees were the first object of the attack,

- before military movements "

- Dresden was virtually undefended. Luftwaffe fighters stationed

in the general vicinity

- were grounded for lack of fuel. With the exception of a few

light guns, the anti-aircraft

- batteries had been dismantled for employment elsewhere.

McKee quotes one British

- participant in the raid, who reported that "our biggest

problem, quite truly, was

- with the chance of being hit by bombs from other Lancasters

flying above us."

- Targets of genuine military significance

were not hit, and had not even been included on

- the official list of targets. Among

the neglected military targets was the railway bridge

- spanning the Elbe River, the

destruction of which could have halted rail traffic for

- months. The railway marshalling

yards in Dresden were also outside the RAF target

- area. The important autobahn bridge

to the west of the city was not attacked. Rubble

- from damaged buildings did interrupt

the flow of traffic within the city, "but in terms of

- the Eastern Front communications

network, road transport was virtually unimpaired."

- In

the course of the USAF daylight raids, American fighter- bombers strafed civilians:

- "Amongst

these people who had lost everything in a single night, panic broke out.

- Women and children

were massacred with cannon and bombs. It was mass murder."

- American aircraft even

attacked animals in the Dresden Zoo. The USAF was still

- at it in late April, with Mustangs

strafing Allied POWs they discovered working in fields.

- The

author concludes that, "Dresden had been bombed for political and not military

- reasons;

but again, without effect. There was misery, but it did not affect the war."

- Some

have suggested that the bombing of Dresden was meant to serve as a warning

- to Stalin

of what sort of destruction the Western Powers were capable of

- dealing. If that was

their intent, it certainly failed to accomplish the objective.

Once word leaked out that the Dresden raids were generally viewed as terrorist attacks against civilians, those most responsible for ordering the bombings tried to avoid their just share of the blame. McKee points out that: "In both the UK and the U.S.A. a high level

of sophistication was to be employed in order to excuse or justify the raids,

or to blame them on someone else. It is difficult to think of any other atrocity

-- and there were many in the Second World War -- which has produced such an

extraordinary aftermath of unscrupulous and mendacious polemics." Who were the men to blame for the attacks? The author reveals that: "It was the

Prime Minister himself who in effect had signed the death warrant for Dresden, which

had been executed by Harris [chief of RAF Bomber Command]. And it was Churchill, too,

who in the beginning had enthusiastically backed the bomber marshals in carrying

out the indiscriminate area bombing policy in which they all believed. They were all in it together. Portal himself [head of the RAF, Harris of course, Trenchard [British air theorist] too, and the Prime Minister most of all. And many lesser people." An aspect of the Dresden bombing that remains

a question today is how many people died during the attacks of February 13-14,

1945. The city was crammed with uncounted refugees and many POWs in transit.

when the raids took place. The exact number of casualties will never be known.

McKee believed that the official figures were understated, and that 35,000 to

45,000 died, though "the figure of 35,000 for one night's massacre alone

might easily be doubled to 70,000 without much fear of exaggeration, I feel." Alexander McKee has written a compelling account

of the destruction of Dresden. Although the author served with the British armed

forces during the war, his attitude toward the events he describes reminds this

reviewer of McKee's fellow Brit, Royal Navy Captain Russell Grenfell, who played

a key role in the sinking of the battleship Bismarck, but who, after the war,

wrote a classic of modern revisionism, Unconditional Hatred: German War Guilt

and the Future of Europe (1953). Likewise, Dresden 1945, deserves a place in any revisionist's library. From The Journal

of Historical Review, Summer 1985 (Vol. 6, No. 2), pages 247-250. ______________________________________________________________________

The ‘Dehousing Paper’ The Real Extermination Policy – How to Murder

25 Million Germans and get away with it

The British R.A.F.

policy to murder at least a third of Germany’s civilian population and

“Break their spirit” – manifested from the ‘Dehousing Paper’ On 30 March 1942, Professor Frederick Lindemann – Baron Cherwell, the British government’s Chief Scientific Adviser (appointed

by Churchill), who wielded more influence than any other civilian adviser and

was said to have “an almost pathological hatred for Germany, and an almost

medieval desire for revenge” as part of his character – sent to the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a memorandum, which after it had been accepted by the Cabinet, became

known as the ‘Dehousing Paper.’ The paper was delivered during a debate within the British government about the most effective use of the nation’s resources in waging war on Germany. Should the Royal Air Force (RAF) be reduced to allow more resources to go to the British Army and Royal Navy, or should the strategic bombing option be expanded to civilian targets?

The paper argued that the demolition of people’s houses (containing mostly

women and children, as men were absent on military duties) was the most effective

way to affect the German morale, even more effectively than killing their relatives.

Given the known limits of the RAF in locating targets in Germany at the time and providing

that the planned resources were made available to the RAF in the near future, destroying about thirty percent of the “Housing Stock” of Germany’s fifty-eight

largest towns was considered the most effective use of the aircraft of RAF Bomber Command, because it would “Break the spirit of the Germans.”

After a heated debate by the government’s military and scientific Advisers,

the Cabinet

voted for the “Expanded” strategic bombing campaign,

over the other options available to them… in complete violation and defiance

of all International Humanitarian Laws, the Hague Conventions, Laws of War and the Geneva Conventions – essentially, voted to approve of committing War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity. Since

November 1941 the RAF had been husbanding its resources and awaiting the introduction

of large numbers of four-engined “heavy” bombers and the GEE radio-navigational device into front-line service.

Bombing policy had, in actuality,

already moved

away from attempts at precision bombing. The paper was produced by Cherwell and the information

was given by the researchers in response to questions posed by Cherwell. Excerpt:

“The

following seems a simple method of estimating

what we could do by bombing Germany. We know from our experience that we

can count on nearly fourteen operational sorties

per bomber produced. The average lift of the bombers we are going to produce over the next fifteen months will be about 3 tons. It follows that each of these bombers

will in its life-time drop about 40 tons of

bombs. If these are dropped on built-up areas they will make 4000–8000 people homeless. In 1938 over 22

million Germans lived in fifty-eight towns of over 100,000 inhabitants, which, with modern equipment, should be easy to find and hit. Our forecast output of heavy bombers (including Wellingtons) between now and the middle of 1943 is about 10,000. If even half the total load of 10,000 bombers were dropped

on the built-up areas of these fifty-eight

German towns, the great majority of their inhabitants (about one-third of the German population) would be turned out of house and home… [that is political linguistics for saying, mass murder, terrorism or genocide] Investigation seems to show that having one’s home demolished is most damaging

to morale. People seem to mind it more than

having their friends or even relatives killed. At

Hull signs of strain were evident, though only one-tenth of the houses were demolished. On the above figures we should be able to do ten times as much harm to each of the fifty-eight principal German towns. There seems little doubt

that this would break the spirit of the people. Our calculation assumes, of course, that we really get one-half of our bombs into

built-up areas. On the other hand, no account

is taken of the large promised American production

(6,000 heavy bombers in the period in question). Nor has regard been paid to the inevitable damage to factories, communications, etc, in these towns and the damage by fire, probably accentuated by breakdown of public services.”

Stated in British Parliament 1943 Lindemann believed that a small circle of the intelligent and the aristocratic should run the world, resulting in a peaceable and stable society, “led by supermen and served

by helots.” Many sources say he was Jewish (HE WAS), others do not,

but for an immigrant born in Germany and the son of a wealthy banker, to hold

such hated toward Germans, one can only surmise. Sometimes considered to be

anti-democratic, insensitive and elitist, Lindemann was in complete support and

promotion of eugenics, he held the working class, homosexuals, Germans and blacks in contempt

and, supported sterilisation of who he saw as mentally incompetent. Referring

to Lindemann’s lecture on Eugenics, Mukerjee concluded science could yield

a race of humans blessed with “the mental make-up of the worker bee” ….At the lower end of the race and class spectrum, one could remove the ability to suffer or to feel ambition….Instead of subscribing to what he called “the fetish of equality,” Lindemann recommended that human differences should be accepted and indeed enhanced by means of science. It was no longer necessary, he wrote, to wait for “the haphazard

process of natural selection to ensure that the slow and heavy mind gravitates

to the lowest form of activity.” Pictures:

Lindemann’s “Housing Stock” turned

“Out of House and Home”

“Dehoused” Holocaust: (frm Greek) Holos Kaustos – ‘Whole Burnt’ Declassified documents confirm the horror of this policy

and that Winston Churchill finds this kind of wanton destruction and terror “Impressive”

– see here “The destruction of German cities, the killing of German workers,

and the disruption of civilized community life throughout Germany is

the goal… It should be emphasized that the destruction of houses,

public utilities, transport and lives; the creation of a refugee problem on an unprecedented

scale; and the breakdown of morale both at home and at the battle fronts by

fear of extended and intensified bombing are accepted and intended aims of our bombing policy. They are not by-products of attempts to hit factories.”

Air Marshal Arthur Harris (aka ‘Bomber Harris’), Bomber Commander, British R.A.F.,

October 25, 1943 – Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare, Tammi Biddle

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), p. 220. “Will there be room [for the German refugees, fleeing before

the Red army] in what is left of Germany? We have killed six or seven

million Germans and probably there will be another million or so killed

before the end of the war.”

– Winston Churchill,

as noted by James F. Byrnes‘ at the Plenary Session at Yalta,

February

7, 1945 – 5 days before the Dresden Holocaust – (H. S. Truman Library,

Independence, Missouri) “The Prime Minister said that we hoped to shatter twenty German cities as we had shattered Cologne, Lubeck, Dusseldorf, and so on. More and more aeroplanes and bigger and bigger

bombs. Marshal Stalin had heard of 2-ton bombs. We had now begun to

use 4-ton bombs, and this would be continued throughout the winter.

If need be, as the war went on, we hoped to shatter almost every dwelling

in almost every German city.”

– Official transcript of

the meeting at the Kremlin between Winston

Churchill and Josef Stalin on Wednesday,