|

Fifteen Years Before Kennedy, Zionists Murdered Forrestal Israel as serial murderer In the 1990s, a couple of bestsellers brought to the knowledge of a large public the fact

that JFK’s assassination in 1963 solved an intense crisis over Israel’s secret nuclear program. In one of his

last letters to Kennedy, quoted by Seymour Hersh in The Samson Option (1991), Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion complained:

“Mr. President, my people have the right to exist […] and this existence is in danger.”[1] The nuclear option was judged vital for Israel, and JFK opposed it. A Haaretz review of Avner Cohen’s book

Israel and the Bomb (1998) puts it this way: “The murder of American President John F. Kennedy

brought to an abrupt end the massive pressure being applied by the US administration on the government of Israel to discontinue

the nuclear program. Cohen demonstrates at length the pressures applied by Kennedy on Ben-Gurion. […] The book implied

that, had Kennedy remained alive, it is doubtful whether Israel would today have a nuclear option.”[2]

Also openly discussed by Israeli historians today are the close connections between Ben-Gurion’s

network in the U.S. and what Tel-Aviv professor Robert Rockaway calls “Gangsters for Zion”, including the infamous “Murder, Incorporated”, run by Bugsy Siegel and then by Mickey Cohen, Jack Ruby’s

mentor. That

Israel had the motive and the means of killing JFK does not prove that Israel did it. But I am quite certain that today,

most smart Israelis assume and half-approve that Ben-Gurion ordered the elimination of JFK in order to replace him by Lyndon

Johnson, whose love for Israel is also now widely celebrated, to the point that some speculate he might have been a secret

Jew. In Ben-Gurion’s mind, making Israel a nuclear state was a matter of life and death,

and obliterating any obstacle was an absolute necessity. In Netanyahu’s mind today, preventing Iran—or any other

enemy of Israel—from becoming a nuclear state is of the same order of necessity, and would surely justify eliminating

another U.S. president in order to replace him by a more supportive Vice President. Most dedicated Zionists understand that.

Andrew Adler, owner and editor in chief of The Atlanta Jewish Times, assumes that the idea “has been discussed

in Israel’s most inner circle,” and, in his column of January 13, 2012, called on the Israeli Prime Minister

to “give the go-ahead for U.S.-based Mossad agents to take out a president deemed unfriendly to Israel

in order for the current Vice-President to take his place and forcefully dictate that the United States’ policy includes

its helping the Jewish State obliterate its enemies. […] Order a hit on a president in order to preserve Israel’s

existence.”[3]

Eliminating unsubmissive foreign leaders is part of Israel’s struggle for existence. Besides, it

is entirely biblical: foreign kings are supposed to “lick the dust at [Israelis’] feet” (Isaiah 49:23),

or perish, with their names “blotted out under heaven” (Deuteronomy 7:24). On November 6, 1944, members of the Stern

Gang, led by future Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, assassinated Lord Moyne, the British resident minister in the Middle

East, for his anti-Zionist positions. The bodies of his murderers, executed in Egypt, were later exchanged for twenty Arab

prisoners and buried at the “Monument of Heroes” in Jerusalem. On September 17, 1948, the same terrorist group

murdered in Jerusalem Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat appointed as United Nations mediator in Palestine. He had

just submitted his report A/648, which described “large-scale Zionist plundering and destruction of villages,”

and called for the “return of the Arab refugees rooted in this land for centuries.” His assassin, Nathan Friedman-Yellin,

was arrested, convicted, and then amnestied; in 1960 he was elected to the Knesset.[4] In

1946, three months after members of the Irgun, led by future Prime Minister Menachem Begin, killed ninety-one people in

the headquarter of the British Mandate’s administration (King David Hotel), the same terrorist group attempted to

murder British Prime Minister Clement Attlee and Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, according to British Intelligence documents

declassified in 2006. These killings and more are documented by Israeli journalist Ronen Bergman in Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations (Random House, 2018). Bergman writes: “At the end of 1947, a report to the British high commissioner

tallied the casualties of the previous two years: 176 British Mandate personnel and civilians killed. / ‘Only these

actions, these executions, caused the British to leave,’ David Shomron said, decades after he shot Tom Wilkin dead

on a Jerusalem street. ‘If [Avraham] Stern had not begun the war, the State of Israel would not have come into being.’”[5]

Absent

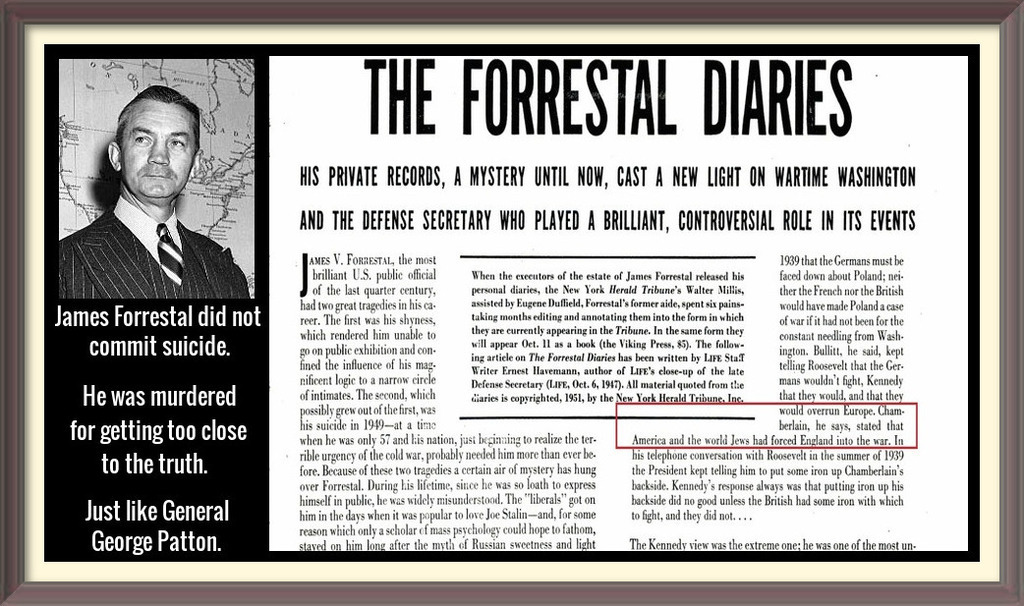

from Israel’s body count in Bergman’s book is former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, assassinated

eight months after Count Bernadotte. Forrestal had been Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Navy from April 1944. With consolidation

of the armed services under Truman in 1947, he became the first Secretary of Defense. He opposed the United Nations’

vote to partition Palestine, and protested vigorously against U.S. recognition of Israel on May 15, 1948, on the ground that

U.S. interests in the Middle East would be seriously jeopardized by American sponsorship of a Jewish state. For this, Forrestal

received “an outpouring of slander and calumny that must surely be judged one of the most shameful intervals in American

journalism,” in the words of Robert Lovett, then Under Secretary of State. Truman replaced Forrestal on March 28,

1949—shortly after his reelection—by the man who had been his main fundraiser, Louis Johnson. According to the

received story, Forrestal, who was psychologically exhausted, fell into depression immediately. On April 2, 1949, he was

interned against his will in the military hospital of the Navy in Bethesda, Maryland, a Washington, DC, suburb, where he

was forcibly confined for seven weeks. He fell to his death from the 16th floor at 1:50 in the morning of May

22, 1949, landing on the roof of the third floor. He had a dressing-gown sash tied around his neck. Bethesda Navy Hospital, where Forrestal met his death National authorities and mainstream

media immediately labeled his death a suicide, without any known criminal investigation. A review board was appointed on

May 23, headed by Admiral Morton Willcutts, to conduct hearings of members of the hospital staff with the sole purpose of

exonerating everyone of responsibility in Forrestal’s assumed suicide. The board completed its work in one week, and

published a short press release four months later. But the full report, containing the transcripts of all hearings an crucial

exhibits, were kept secret for 55 years, until David Martin obtained it through a Freedom of Information Act request in

April 2004 (it is now available on the Princeton University Library website in pdf form, or here in HTML rendition by the anonymous Mark Hunter, who makes useful comments). In

his book and in his web articles complementing it, David Martin makes a compelling case that Forrestal was murdered, and that his murder was ordered by

the Zionists, most probably with the knowledge and approval of Truman, who was then completely hostage to the Zionists.

The motive? Forrestal was planning to write a book and to launch a national magazine: he had the money and the connections

for it, and he had three thousand pages of personal diary to back his revelations on the corruption of American leadership

and the sell-out of American foreign policy to communism under Roosevelt, and to Zionism under Truman. I will here summarize

the evidence accumulated by David Martin, and highlight the significance of this case for our understanding of Israel’s

takeover of the heart, soul, and body of the United States. Unless specified otherwise, all information is from Martin’s

book or articles. My

own interest for this heartbreaking story stems from my interest for the Kennedy assassinations. (read my article “Did Israel Kill the Kennedys?”). I found the connection and similarities between the two stories highly illuminating. Everyone knows that Kennedy was

assassinated, yet most Americans are still unaware of the evidence incriminating Israel. In the case of Forrestal, it is

the opposite: few people suspect a murder, but once the evidence for murder has been presented, it points directly to Israel

as the culprit. For this reason, Forrestal’s assassination by the Zionists becomes a precedent that makes JFK’s

assassination by the same collective entity more plausible. If Israel can kill a former U.S. Defense Secretary on American

soil in 1949 and get away with it with government and media complicity, then why not a sitting President fifteen years later?

If the truth on Forrestal had been known by 1963, it is unlikely that Israel could have killed two Kennedys with impunity. Forrestal was of Irish

Catholic origin like the Kennedys, and was close to JFK’s father. Both James Forrestal and Joseph Kennedy are examples

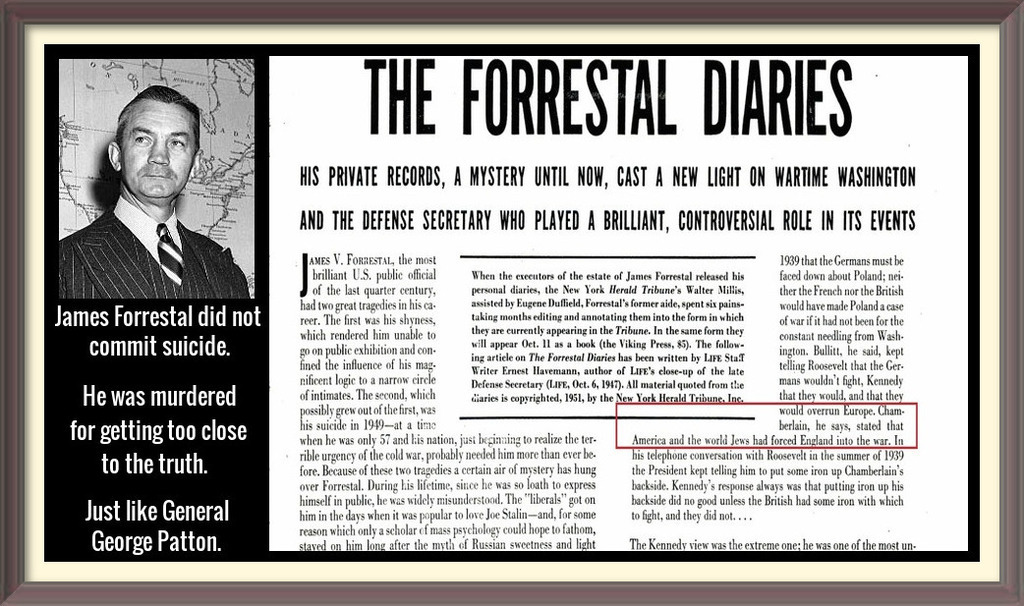

of American patriots of Irish stock who were alarmed by Jewish influence over American foreign policy. The entry for 27 December 1945 in Forrestal’s edited diary, says: “Played golf with Joe Kennedy. I asked him about his conversations

with Roosevelt and Neville Chamberlain from 1938 on. […] Chamberlain, he says, stated that America and the world

Jews had forced England into the war.”

One major difference between the two men is that Joe Kennedy had resigned

from government after Roosevelt’s entry into the war, and had kept a low profile on Israel. Moreover, unlike Forrestal,

he was the head of a wealthy clan and had his own men in the press. He was a politician, whereas Forrestal was an uncompromising

man. These differences explain why Forrestal was assassinated, whereas Joe had his son elected president. Yet in the end,

the Kennedys suffered the Talmudic curse over three generations. When James Forrestal, hostile to Stalin’s ambitions on Eastern

Europe and to Truman’s decision to nuke Japan, was kept away from the official delegation to the Potsdam Conference

in the summer 1945, he flew there privately and took with him the then 28-year-old John Kennedy, for a tour of post-war

Germany. Later on, John integrated James Forrestal’s son Michael Forrestal as a member of his National Security Council. In May 1963 he made a symbolic public gesture by visiting the grave of James

Forrestal on Memorial Day. JFK visits Forrestal’s grave at Arlington cemetery James Forrestal’s

and John Kennedy’s assassinations bear one sinister thing in common: Bethesda Naval Hospital. As most readers recall,

this is where Kennedy’s autopsy was tampered with after his body had been whisked away at gunpoint from Dallas Parkland

Hospital, most probably by Secret Service agents on Lyndon Johnson’s order. In 1963, Lyndon Johnson could count on

high-level complicity within the Navy. It happens that Johnson, whom Billy Sole Estes claims ordered nine murders in the course of

his political career,[6] makes a special appearance, although brief and poorly documented, in the story of Forrestal’s assassination. LBJ

was then a newly elected congressman, on the payroll of Abraham Feinberg, former president of Americans for Haganah Incorporated

and financial godfather of Israel’s atomic bomb.[7] According to the testimony of Forrestal’s assistant Marx Leva (more on him later), Johnson paid an unwanted visit

to Forrestal at Bethesda Hospital. David Martin asks: “Could LBJ have been playing something of a foot-soldier

role for the orchestrators of Forrestal’s demise? Might he have been there to size up the overall situation, and at

the same time contribute to ‘making his bones,’ as it were, by participating in such an important operation?”

(Martin p. 20)

It

bears repeating that no investigation was conducted into the death of James Forrestal, either by the FBI or the NCIS (Navy

Criminal Investigative Service). The very day of his death, the mainstream press announced his suicide as a matter of fact.

The New York Times stated in its late May 22 edition that Forrestal “jumped thirteen stories to his death,”

and added the next morning: “There were indications that Mr. Forrestal might also have tried to hang himself.

The sash of his dressing-gown was still knotted and wrapped tightly around his neck when he was found, but hospital officials

would not speculate as to its possible purpose.”

Later biographers did speculate that he may have tried

to hang himself but failed to tie the sash securely to the radiator beneath the window. In The Man Who Kept the Secrets,

Pulitzer Price winner Thomas Powers says that Forrestal died trying to hang himself “from his hospital window, but

slipped and fell sixteen stories to his death.” Forrestal left no suicide note, but the New York Times (May

23) informs its readers that: “A book of poetry beside his bed was opened to a passage from the Greek tragedian,

Sophocles, telling of the comfort of death. […] Mr. Forrestal had copied most of the Sophocles poem from the book

on hospital memo paper, but he had apparently been interrupted in his efforts. His copying stopped after he had written

‘night’ of the word ‘nightingale’ in the twenty-sixth line of the poem.”

On May 24, the New

York Times gave the final word to the psychiatrist in charge, who made suicide sound predictable: “Captain

George M. Raines, the Navy psychiatrist who had been treating Mr. Forrestal, said that the former Secretary ended his life

in a sudden fit of despondency. He said this was ‘extremely common’ to the patient’s severe type of mental

illness.”

That’s it. Never did the mainstream media hint at the possibility of foul play. The

conclusion that Forrestal’s death is an obvious suicide caused by his “mental illness” was taken at face

value by the authors of Forrestal’s two main biographies: - Arnold Rogow, James Forrestal, A Study of Personality, Politics, and Policy (MacMillan Company, 1963);

- Townsend Hoopes and Douglass Brinkley, Driven Patriot, the Life and Times of James Forrestal (Alfred A.

Knopf, 2003).

Rogow, whose book has been called a “psychological autopsy,” insists on linking Forrestal’s

alleged mental illness to his alleged anti-Semitism, with the implication that anti-Semitism is a form of paranoia that may

lead to suicide. Rogow is an expert on the subject of anti-Semitism, on which he wrote the article for The International

Encyclopedia of Social Science. He is also the author The Jew in a Gentile World: An Anthology of Writings about

Jews by Non-Jews. Hoopes and Brinkley borrow heavily from Rogow, but add valuable information based on their own interviews.

They give an interesting interpretation of the morbid poem allegedly copied by Forrestal from Mark Van Dorren’s Anthology

of World Poetry, titled “The Chorus from Ajax.” Taking their clue from Zionist apologist John Loftus, author

of The Belarus Secret (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982), they speculate that, when reaching the word “nightingale”

in the poem, Forrestal might have been overwhelmed by a sudden rush of guilt for having authorized a CIA operation with the

code name of “Nightingale,” that infiltrated into the Soviet Union Ukrainian spies who had been formerly Nazi

collaborators and probably killers of Jews. The word “nightingale,” Hoopes and Brinkley surmise, must have triggered

Forrestal’s urge to take the poet’s admonition literally and end his life on the spot. David

Martin has uncovered grave inconsistencies and outright lies in the official story. First, it appears that Forrestal’s

nervous breakdown has been wildly exaggerated, if not totally invented. As the story goes, Forrestal’s mental health

had started deteriorating before Truman replaced him, and collapsed on March 29, just after a brief ceremony in his honor

at Capitol Hill. The main source for this story is an Oral history interview of Marx Leva, Forrestal’s special assistant at that time, recorded for the Truman library in 1969. Leva says that, on that day,

he found Forrestal in his Pentagon office, “almost in a coma.” He had him driven home and later met him there

with Forrestal’s friend Ferdinand Eberstadt, and the two men decided that Forrestal’s state required that he

urgently take some vacation. So Leva made immediate arrangement for a Marine plane to fly him to the estate of Robert Lovett

in Hobe Sound, Florida that very night. “And on the way out Forrestal said three times, the only thing he said, [Eberstadt]

tried to speak to him and he would say, ‘You’re a loyal fellow, Marx.’ ‘You’re a loyal fellow,

Marx,’ three times.” Since Leva is Jewish, the implication is that Forrestal was obsessed by the disloyalty

he attributed to many Jewish officials. For Leva, “he apparently was beyond being neurotic, I mean it was apparently

paranoid”. David Martin shows in this article (adding a new perspective to his book) that Marx Leva is lying. Forrestal’s vacation had in fact been planned in

advance, and his wife was already waiting for him there. This is proven by a Jacksonville Daily Journal article

dated March 28 about the ceremony when Truman pinned the Distinguished Service Medal on Forrestal’s chest that very

day. The article concludes: “Forrestal is flying tomorrow to Hobe Sound, Fla., for a long rest.” This video clip of Forrestal shows him perfectly healthy and composed on March 28. News reports and biographies insist that, during his

four-day stay at Hobe Sound, Forrestal showed signs of paranoia. One rumor, made up by Daniel Yergin and repeated by Thomas

Powers in The Man Who Kept the Secrets, has him running through the streets yelling, “The Russians are coming.”

There is no credible source for this claim. Under Secretary of State (and future Defense Secretary) Robert Lovett, who was

at Hobe Sound with Forrestal, did say in 1974 that Forrestal appeared to him as “not of sound mind,” because

“he was obsessed with the idea that his phone calls were being bugged,” and complained that “they’re

really after me.” I find rather strange, though, that Lovett feigns to ignore who Forrestal meant by “they”.

There is nothing irrational in Forrestal’s belief that “his telephones were being bugged, [and that] his house

was being watched”, as he had earlier complained to Truman’s appointments secretary, Matthew J. Connelly (who

said so in a 1968 interview by the Truman Library). There is also a rumor that Forrestal attempted suicide at Hobe Sound. It is contradicted by the Willcutts

report, where Dr. George Raines, the psychiatrist in charge of Forrestal at Bethesda, is recorded stating: “So far

as I know he never made a single real attempt at suicide except that one that was successful.” All of Forrestal’s

doctors interviewed are unanimous that he had never attempted suicide before his fatal fall.

That is not to say that Forrestal

was not psychologically strained in 1949. As Secretary of Defense, he had been subjected not only to slander and calumny

by the press, but also to anonymous death threats. Robert Lovett, who shared Forrestal’s views on Israel, testified

that he himself received night phone calls with death threats, and that Forrestal was more exposed than him to this kind

of treatment. Having lost all protection from the government after March 28, Forrestal had reasons to fear for his life.

On May 23, 1949, The Washington Post concluded an article headlined “Delusions of Persecution, Acute Anxiety,

Depression Marked Forrestal’s Illness,” with the somewhat paradoxical statement:

“His

fear of reprisals from pro-Zionists was said to stem from attacks by some columnists on what they said was his opposition

to partition of Palestine under a UN mandate. In his last year as Defense Secretary, he received great numbers of abusive

and threatening letters.”

John Loftus and Mark Aarons, the arch-Zionist authors of The Secret

War against the Jews, identify Forrestal as “the principal villain, the man who nearly succeeded in preventing

Israel’s birth.” They reveal that “The Zionists had tried unsuccessfully to blackmail Forrestal with tape

recordings of his own deals with the Nazis” (before the war, Forrestal had been a partner of Clarence Dillon, the

Jewish founder of the banking firm Dillon, Read, and Co.), but they believe that Zionist harassment at least succeeded in

making him insane: “His paranoia convinced him that his every word was bugged. / To his many critics, it seemed that

James Forrestal’s anti-Jewish obsession had finally conquered him.”[8] How

convenient to claim that anti-Semitism may lead to suicide. When the Zionist mafia wishes you dead, fearing for your life

is not a sign of mental illness, but rather of sound judgment. We need not doubt Raines’ words to the Willcutts Review Board

that, when he first saw Forrestal at Bethesda Hospital, “he was obviously exhausted physically” and showed “high

blood pressure.” But here, we also have to take into account that Forrestal had been literally abducted from his vacation

center at Hobe Sound. We should not be surprised when Rogow, and Hoopes and Brinkley after him, tell us that, even though

he had been sedated, Forrestal “was in a state of extreme agitation during the flight from Florida,” and that: “Forrestal’s

agitation increased during the trip in a private car from the airfield to the hospital. He made several attempts to leave

the car while it was in motion, and had to be forcibly restrained. Arriving at Bethesda, he declared that he did not expect

to leave the hospital alive.”

As Martin mentions, there is also the very real possibility that Forrestal

had been drugged at Hobe Sound, in order to make him appear insane and justify his internment.

Forrestal’s behavior at

Bethesda shows nothing abnormal for a man locked up in the psychiatric division of a military hospital, on the 16th

floor, for reasons he feared were not strictly medical. It has been reported by medical personnel that Forrestal often seemed

restless, walking back and forth in his room late at night. Why wouldn’t he? Forrestal was even denied visits by those

dearest to him. His brother Henry had tried several times to visit him, but had been rebuffed by Dr. Raines. The hospital

authorities relented only after Henry threatened legal action. Forrestal was also denied the visit of his friend the Catholic

priest, Monsignor Maurice Sheehy. Sheehy wrote in The Catholic Digest, January 1951, that, “The day he was

admitted to the hospital, Forrestal told Dr. Raines he wish to see me,” but that Dr. Raines told him “that Jim

was so confused I should wait some days before seeing him.” Raines turned away Father Sheehy on six occasions. Despite being kept

in virtual imprisonment and under forced medication, Forrestal endured remarkably well. From the hearings conducted by the

Willcutts Review Boards, it appears that he was doing fine, in the days preceding his death. Willcutts himself expressed

surprise at learning about his death, because he had dinner with him one day earlier (Friday the 20th), and thought

he was “getting along splendidly.” As

mentioned earlier, the Willcutts Review Board’s mission was to exonerate every single individual of negligence. Even

the brief conclusions released four months after it concluded its hearings, admits so, as reported in the New York Times

October 12, 1949: “Francis P. Matthews, Secretary of the Navy, made public today the report of an investigating

board absolving all individuals of blame in the death of James Forrestal last May 22.”

Strangely enough,

as Martin discovered, the report states that Forrestal’s fall was the cause of his death, but avoids any statement

about the cause of the fall itself. There is an obvious lack of interest from the Willcutts Board regarding all elements that

point to murder rather than to suicide. The nurse who first entered Forrestal’s room after his death testified that

there was broken glass on his bed. But the room must have been laundered before the crime scene photographs were taken,

because they show the bed with nothing but a bare mattress, while another picture shows broken glass on the carpet at the

foot of his bed (photos available on Mark Hunter’s site). The Willcutts Board had no interest in finding the origin of the broken glass, nor the reason it was removed from the bed. They also failed to

ask the personnel or themselves any relevant questions about the gown sash tied around Forrestal’s neck. Hoopes and

Brinkley later speculated that Forrestal tied the sash to a radiator beneath the window, but that his knot “gave way.”

That is contradicted by hospitalman William Eliades, who found the body of Forrestal with the sash (cord) around his neck,

and declared to the Willcutts Review Board: “I looked to see whether he had tried to hang himself and whether a piece

of cord had broken off. It was still in one piece except it was tied around his neck.”

But the most compelling proof

that Forrestal’s death has been disguised as a suicide is the poem allegedly copied by Forrestal. Among the exhibits

obtained by Martin alongside the Willcutts report is a copy of the memo sheet with the transcription of the poem (here). A comparison with any handwritten note by Forrestal makes it plain that it was not copied by Forrestal (both can be found

on Mark Hunter’s webpage).

A sample of Forrestal’s handwriting and the note supposedly found in his room

As Martin comments, “One hardly needs an expert to tell him that the person who transcribed the poem is not the same person who wrote

the various letters there.” Martin also notes that, from this single page, it is doubtful that the writer, whoever

he was, even reached the word “nightingale”, which appears 11 verses below in the poem. Interestingly, no

one is identified in the official report as the discoverer of this handwritten note. It didn’t occur to the members

of the Review Board to mention how it came into their possession, and to question about it the person who gave it to them. In an effort to make

the note a convincing proof of suicide, Rogow claims, and Hoopes and Brinkley repeat, that Apprentice Robert Wayne Harrison,

Jr., the corpsman on duty to keep watch on Forrestal, checked into his room at 1:45 and saw him copying the poem. But by

doing so, they both contradict Harrison’s declaration to the Willcutts Board. He said that, when he checked on him

at 1:45, Forrestal was “in his bed, apparently sleeping.” Then he went to fill in the medical chart. Minutes

later, a nurse heard the sound of Forrestal’s body striking the third floor roof. Harrison heard nothing but then

became aware that Forrestal was missing at 1:50. Robert Wayne Harrison, Jr. would certainly have been a prime suspect

if any criminal investigation had taken place. He was new to the job, and unknown to Forrestal until that fatal night. He

had started his guard at midnight, replacing Edward Prise whose shift had started at 4 pm. Prise was well-known and apparently

appreciated by Forrestal; he had been assigned to keep watch on Forrestal from the third day of Forrestal’s arrival

at Bethesda. Strangely, his name is not mentioned in any contemporary news report, and it is misspelled “Price”

in the report and in all biographies, although he clearly signed “Prise” in the medical chart included among

the exhibits with the Willcutts report. David Martin mentions that he received an e-mail from Prise’s daughter saying: “We

grew up hearing whispers between our parents in reference to this matter but were not allowed to ask for detail. Even up

until a year prior to my father’s death in 1991 he had called me and was in fear that he was going to be questioned

again about the issue.” (Martin p. 9)

We need not insist on the fact that witnesses are easily intimidated

in a military environment, as was Bethesda Hospital. The pressure transpires in the transcripts of the Willcutts interviews:

every nurse, corpsman or doctor said what they were expected to say, and understood their obligation never to speak otherwise.

An interesting insight into this can be gained from David Martin’s interview of John Spalding, James Forrestal’s Navy Driver, then 27 years-old. When informed of the death of Forrestal by his superior, Spalding

was handed a sheet of paper to sign, saying “I could never talk about anything that happened between him and me.” Before

David Martin, one author, writing under the pen-name Cornell Simpson, had claimed that Forrestal had been murdered. His

book, The Death of James Forrestal, was published in 1966, although he claims to have written it in the mid-1950s.

Simpson’s book contains much valuable and credible information. He had for example interviewed James Forrestal’s

brother Henry, who was positively certain that his brother had been murdered. Henry Forrestal found the timing of the death

very suspicious because he was coming to take his brother out of the hospital a few hours later that very same day. According

to Simpson, another person who didn’t believe in Forrestal’s suicide was Father Maurice Sheehy. When he hurried

to the hospital several hours after Forrestal’s death, he was approached discreetly by an officer who whispered to

him, “Father, you know Mr. Forrestal didn’t kill himself, don’t you?”

Simpson blames the communists

for Forrestal’s murder. The claim is not preposterous. Forrestal was definitely anti-communist. He had been alarmed

by what he saw as communist infiltration in the Roosevelt administration (the Venona decrypts, giving evidence of 329 Soviet agents inside the U.S. government during World War II, would prove him right). After Roosevelt’s

death, he was influential in the transformation of U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union, from accommodation to “containment.”

Senator Joseph McCarthy, another Irish Catholic, testifies in his book The Fight for America that it was Forrestal

who directly inspired his exposés of communist influence and subversion in the federal government: “Before

meeting Jim Forrestal I thought we were losing to international Communism because of incompetence and stupidity on the part

of our planners. I mentioned that to Forrestal. I shall forever remember his answer. He said, ‘McCarthy, consistency

has never been a mark of stupidity. If they were merely stupid they would occasionally make a mistake in our favor.’

This phrase stuck me so forcefully that I have often used it since.”

After Forrestal met his violent

end, McCarthy moved up to the front line. He himself died on May 2, 1957, at the age of forty-eight, in Bethesda Hospital.

Hospital officials listed the cause of death as “acute hepatic failure,” and the death certificate reads “hepatitis,

acute, cause unknown.” The doctors declared that the inflammation of the liver was of a “noninfectious type”.

Acute hepatitis can be caused either by infection or by poisoning, yet no autopsy was performed. Simpson comments (as quoted

at length in Martin’s article “James Forrestal and Joe McCarthy”): “Like Jim Forrestal, Joe McCarthy walked into the Bethesda Naval Hospital as its most controversial

patient and as the one man in America most hated by the Communists. And, like Forrestal, he left in a hearse, as a man whose

valiant fight against Communism was ended forever.”

M. Stanton Evans, who built on his father Medford Evans’

earlier work for his commendable Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight Against America’s Enemies (2009), hints at the possibility that McCarthy was murdered, but does not explore the issue. In 1953, Robert Kennedy worked as an assistant counsel to the Senate committee chaired by Senator

Joseph McCarthy The problem with Cornell Simpson’s theory is that Forrestal’s worst enemies were not the communists,

but the Zionists. Although Forrestal’s anti-communism later attracted criticism from left-wing historians, it was

not, then, a matter of public condemnation. Forrestal’s anti-communism was shared by most of his contemporaries, especially

within the military. As long as you did not mention the high percentage of Jews among communists, being anti-communist did

not make you the target of the mainstream media. The same, obviously, cannot be said of anti-Zionism. Neither the Washington

Post nor the New York Times can be said to have been pro-communist at any time, but both turned strongly pro-Zionist

around 1946. Arthur Hays Sulzberger, the NY Times’ director of publication since 1938, had actually denounced

in 1946 the “coercive methods of the Zionists” influencing his editorial line, but eventually gave in and, since

1948, the NY Times has produced singularly unbalanced coverage of Palestine.[9] It

was his opposition to Zionism, not to communism, that attracted death threats to Forrestal. In his diary entry for February

3, 1948, Forrestal writes that he had lunch with Bernard Baruch and mentioned to him his effort at stopping the process

of recognition: “He took the line of advising me not to be active in this particular matter and that

I was already identified, to a degree that was not in my own interests, with opposition to the United Nations policy on

Palestine.”

Martin comments (p. 86): “Baruch clearly did not know his man when he attempted

to influence him by appealing to Forrestal’s own self-interest. He might have known more than he was telling, though,

when he hinted at the danger that Forrestal faced for the courageous position he had taken.”

Jewish gangsters were

traditionally anti-communists, but the Zionists could count on them to give a hand whenever needed. From 1945, Ben-Gurion’s

Jewish Agency had close links to the Yiddish mafia, also known as the Mishpucka (Hebrew for “the Family”), who

contributed greatly to the clandestine arms-purchasing-and-smuggling network that armed the Haganah. Leonard Slater writes

in The Pledge that Teddy Kollek, who later became the longtime mayor of Jerusalem, ran the day-to-day operations and was told

explicitly by Jewish gangsters from Brooklyn, “If you want anyone killed, just draw up a list and we’ll take

care of it.” Yehuda Arazi, a close aide to Ben-Gurion sent by him to the U.S. to purchase heavy armaments, approached

Meyer Lansky and met with members of “Murder, Incorporated.” Another Haganah emissary, Reuvin Dafni, who would

become Israeli consul in Los Angeles and New York, met with Benjamin Siegelbaum, known as Bugsy Siegel. Some of those “gangsters for Zion”, writes Robert Rockaway, “did so out of ethnic loyalties,” or “saw themselves as defenders of the Jews,

almost biblical-like fighters. It was part of their self-image.” Some also helped “because it was a way […]

to gain acceptance in the Jewish community.”[10] Mickey Cohen, the successor of Bugsy Siegel, explains in his memoirs that from 1947, “I got so engrossed with Israel

that I actually pushed aside a lot of my activities and done nothing but what was involved with this Irgun war.”[11] He was in close contact with Menachem Begin, and met with him when Begin came touring the U.S. in December 1948, a few

months before Forrestal was confined to the Bethesda hospital.[12] Had Begin wanted Forrestal dead, he had only to ask. I think it is quite self-evident that Forrestal had more to fear from

the Zionists than from the communists. And so it is strange that Cornell Simpson totally ignores the Zionists as possible

culprits. Neither Israel nor Zionism appears in his index. David Martin, who nevertheless recognizes the merit of Simpson’s

investigation, finds the explanation for his blackout on Zionism in the fact that his book was published by Western Islands

Publishers, the in-house publishing company of the John Birch Society, a Zionist front. Three

years before the Birch Society published Simpson’s book, Rogow had published the first biography of Forrestal, defending

the official line about his death, and linking his supposed mental illness directly to his supposed anti-Semitism. It is

very unlikely that Rogow’s book eased the suspicions of the skeptics about Forrestal’s suicide. On the contrary,

Rogow’s obvious bias as a writer mainly concerned with anti-Semitism must have led many to consider his book as just

another layer in the cover-up. Martin therefore speculates that the writing and publishing of Simpson’s book by the

Birch Society was a way to give voice to the skepticism over Forrestal’s death, while directing that skepticism away

from the most likely suspects. Blaming the communists was the easiest way to deflect suspicions from the Zionists. It was all the easier

that, from the 1930s up to the time of Forrestal’s death, the communists and the Zionists were the same people in many

instances, as David Martin points out. Although communism and Zionism may seem incompatible from an ideological viewpoint,

it is a matter of record that some of the Jews who acted as communist agents under Roosevelt, turned ardent Zionists under

Truman. A case in point is David Niles (Neyhus), one of the few of FDR’s top advisors kept by Truman: he was identified in the Venona decrypts as a communist

agent, but then played a key role as a Zionist gatekeeper under Truman. Edwin Wright, in The Great Zionist Cover-Up, names him as “the protocol officer in the White House, [who] saw to it that the State Department influence

was negated while the Zionist view was presented.” David Niles’ brother Elliot, a high official of B’nai

B’rith, was a Lieutenant Colonel who passed information to the Haganah while working in the Pentagon. Martin

considers David Niles “the most likely coordinator of the Forrestal assassination.” He had the motives and the

means. He was actually capable of passing orders on behalf of Truman, as he did when orchestrating the campaign of intimidation

and corruption that obtained a two-third majority in favor of the Partition Plan at the U.N. General Assembly.[13] There

are reasons to believe that the order to eliminate Forrestal came directly from the White House. According to Truman’s

appointments secretary, Matthew J. Connelly, it was Truman himself who suggested arranging for Forrestal a vacation at Hobe

Sound. As for the decision to abduct him from there and intern him in Bethesda, Martin makes the following remark: “Considering

the fact that Forrestal, having been officially replaced as Defense Secretary by Johnson on March 28, was a private citizen

at this point, it is certainly reasonable to assume that Forrestal’s extra-legal transportation to Florida on a military

airplane and confinement and treatment in the Naval Hospital at Bethesda was not done without approval at the highest level.”

(Martin p. 29)

Hoopes and Brinkley state explicitly that the decision to take Forrestal to Bethesda came

from Truman, and that Forrestal’s wife was convinced by a telephone conversation with Truman. The decision to put

Forrestal on the 16th floor, which seems hardly appropriate for a patient reputed suicidal, also came from the

White House. Hoopes and Brinkley quote Dr. Robert P. Nenno, a young assistant to Dr. Raines from 1952 to 1959, who believed

that Raines had received instruction to put Forrestal there, and added, “I have always guessed that the order came

from the White House.” Hoopes and Brinkley justify Dr. Raines’ turning Sheehy away on six occasions by the

fear that Forrestal might divulge sensitive information during confession. Such concerns obviously came from higher up. It

apparently didn’t come from Navy Secretary John L. Sullivan because, as Hoopes and Brinkley tell us, when Sheehy and

Henry Forrestal took their complaint to him on May 18, he expressed surprise and had the decision overruled. According to

Simpson: “the priest later commented that he received the distinct impression that Dr. Raines was acting under orders.” There is, of course,

no evidence that throwing Forrestal out of the window was also ordered by the White House, but given Truman’s complete

control by the Zionists, and by David Niles in particular, it is not unlikely. But,

one may ask, why would Truman or anyone need to kill Forrestal? Once out of the Pentagon, he had no more influence on government

policy. The

answer is easy. Far from being suicidal, Forrestal was a man with a plan. According to Hoopes and Brinkley, “he

had told powerful Wall Street friends […] that he was interested in starting a newspaper or a magazine modeled after

The Economist of Great Britain, and they had demonstrated a willingness to help him raise the start-up funds.”

He also planned to write a book. With no more ties to the government or to the army, he was free to speak

his mind on many issues. As a war hero and a very popular figure, he was sure to have a great impact. And he had plenty

of embarrassing things to reveal about what he had seen during his nine years in the government.

Time cover, October 29, 1945 As Navy Secretary, he had been the central person

for Pacific operations during World War II. He had inside knowledge of Roosevelt’s scheme to provoke the Japanese

into attacking Pearl Harbor. According to his diary entry for April 18, 1945, he had even told Truman, that, “I

had got Admiral Hewitt back to pursue the investigation into the Pearl Harbor disaster. […] I felt I had an obligation

to Congress to continue the investigation because I was not completely satisfied with the report my own Court had made.”

Forrestal was also very bitter about the way the war ended in the Pacific. Knowing the desperate situation

of the Japanese, he had worked behind the scene to achieve a negotiated surrender from the Japanese. He was opposed to the

demand of “unconditional surrender”, which he knew was unacceptable to the Japanese military leadership. Simpson

writes, as quoted by David Martin here: “As secretary of the navy, Forrestal had originated a plan to end the war with Japan five and a half

months before V-J Day finally dawned. He had mapped this plan on the basis of massive intelligence information obtained

on and prior to March 1, 1945, to the effect that the Japanese were already desperately anxious to surrender and the fact

that the Japanese emperor had even asked the pope to act as peace mediator. If Roosevelt had acted on Forrestal’s

plan, the war would have ground to a halt in a few days. A-bombs would never have incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, thousands

of Americans would not have died in the unnecessary battle of Okinawa and later bloody encounters, and the Russians would

not have had a chance to muscle into the Pacific war for the last six of its 1,347 days, thus giving Washington the pretext

for handing them the key to the conquest of all Asia.”

Forrestal had also much to say about the

way the Zionists obtained the Partition Plan at the General Assembly of the United Nations, or about the way Truman was

blackmailed and bought into supporting the recognition of Israel. He had written in his diary, February 3, 1948, about his

meeting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., a strong advocate of the Jewish State: “I thought the methods

that had been used by people outside of the Executive branch of the government to bring coercion and duress on other nations

in the General Assembly bordered closely onto scandal.”

Forrestal had a pretty good memory. But,

in addition, he had accumulated thousands of pages of diary during his public service. According to Simpson, “During

Forrestal’s brief stay at Hobe Sound, his personal diaries, consisting of fifteen loose-leaf binders totaling

three thousand pages, were hastily removed from his former office in the Pentagon and locked up in the White House where

they remained for a year. […] all during the seven weeks prior to Forrestal’s death, his diaries were out of

his hands and in the White House, where someone could have had ample time to study them.”

The White House later

claimed that Forrestal had sent word that he wanted President Truman to take custody of these diaries, but that is very

unlikely. A

small part of Forrestal’s diaries was ultimately published in a heavily censored form by Walter Millis, FDR apologist

and New York Herald Tribune journalist. Simpson estimates that more than 80 percent was left out. Millis frankly

admitted that he had deleted unfavorable “references to persons, by name [and] comment reflecting on the honesty or

loyalty of an individual.” Millis also said that he deleted everything on the Pearl Harbor investigations. One can

only guess how much censorship Millis exerted on Forrestal’s view about American support for Israel. David Martin’s

conclusion makes perfect sense: “Forrestal’s writing and publishing plans provide the answer to the question,

‘Why would anyone bother to murder him when he had already been driven from office and disgraced by the taint of mental

illness?’” “The

compelling reasons for Forrestal to want to continue living were also compelling reasons for his powerful enemies to see

to it that he did not.” “He

comes across, in short, not as a prime candidate for suicide, but for assassination.” (Martin, pp. 52, 53, 87)

In

his blurb for Martin’s book, James Fetzer puts it this way: “Dave Martin has established that James Forrestal

was targeted for assassination by Zionist zealots who were convinced that his future influence as an editor and publisher

represented an unacceptable risk.”

In this article, Martin expands on this idea by comparing Forrestal to Lord Northcliffe (Alfred Harmsworth), an influential newspaper editor

whose tragic story is told by Douglas Reed in The Controversy of Zion (pp. 205-208), based on The Official History of The Times (1952). In the 1920s just like today, factual reporting

from the press was the greatest obstacle to the Zionist ambitions. Lord Northcliffe owned journals and periodicals, including

the two most widely read daily newspapers, and he was the majority proprietor of the most influential newspaper in the world

at that time, The Times of London. He took a definite stand against the Zionist plan, and wrote, after a visit to

Palestine in 1922: “In my opinion we, without sufficient thought, guaranteed Palestine as a home for the Jews despite

the fact that 700,000 Arab Moslems live there and own it.” Northcliffe commissioned a series of article attacking

Balfour’s attitude towards Zionism. His editor, Wickham Steed, refused, and, when Northcliffe asked him to resign,

took a series of action to have Northcliffe declared mentally ill. Although he appeared perfectly normal to most people he

met, on June 18, 1922, Northcliffe was declared unfit for the position of editor of The Times on the authority

of an unknown “French nerve specialist,” removed from all control of his newspapers, and put under constraint.

On July 24, 1922 the Council of the League of Nations met in London, secure from any possibility of loud public protest by

Lord Northcliffe, to bestow on Britain a “mandate” to remain in Palestine and to install the Zionists there.

On August 14, 1922, Northcliffe died at the age of fifty-seven, officially of “ulcerative endocarditis.” The

public was, of course, kept in total ignorance of the way this highly respected public figure was taken off the scene. Douglas

Reed, who was then working as a clerk in the office of The Times, and learned the full story much later, remembers

that: “Lord Northcliffe was convinced that his life was in danger and several times said this; specifically,

he said he had been poisoned. If this is in itself madness, then he was mad, but in that case many victims of poisoning

have died of madness, not of what was fed to them. If by any chance it was true, he was not mad. […] His

belief certainly charged him with suspicion of those around him, but if by chance he had reason for it, then again it was

not madness.”

Reed sees Northcliffe’s elimination as a turning point:

“After

Lord Northcliffe died the possibility of editorials in The Times ‘attacking Balfour’s attitude towards

Zionism’ faded. From that time the submission of the press […] grew ever more apparent and in time reached

the condition which prevails today, when faithful reporting and impartial comment on this question has long been in suspense.”

The parallel with Forrestal is indeed striking, as David Martin remarks:

“Forrestal’s

first love was journalism. In his youth he had worked as a reporter for three newspapers in his native upstate New York,

and he had been the editor of the student newspaper at Princeton. As former president of the investment banking firm of

Dillon, Read, & Co. he was a rich, powerful and well-connected man. He had plans to run his own news magazine. In short,

he could have become an American Lord Northcliffe with the ability to have a great deal of influence on public opinion in

the country.”

Notes [1] Seymour Hersh, The Samson Option: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy, Random House, 1991,

p. 141. [2] Haaretz, February 5, 1999, quoted in Michael Collins Piper, False Flags: Template for Terror, American

Free Press, 2013, pp. 54–55. [3] Joe Sterling, “Jewish paper’s column catches Secret Service’s eye,” CNN, January 22, 2012. [4] Alan Hart, Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, vol. 2: David Becomes Goliath, Clarity Press, 2013, p.

90. [5] Ronen Bergman, Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations, Random House,

2018, p. 20. [6] William Reymond and Billie Sol Estes, JFK Le Dernier Témoin, Flammarion, 2003.

[7] Alan Hart, Zionism: The Real Enemy of the Jews, vol. 2: David Becomes Goliath, Clarity Press, 2013, p.

250. [8] John Loftus and Mark Aarons, The Secret War against the Jews: How Western Espionage Betrayed The Jewish People, St.

Martin’s Griffin, 2017 , p. 212-213. [9] Alfred Lilienthal, What Price Israel? (1953), Infinity Publishing, 2003, pp. 95, 143.

[10] Robert Rockaway, “Gangsters for Zion. Yom Ha’atzmaut: How Jewish mobsters helped Israel gain its independence”,

April 19, 2018, on tabletmag.com [11] Mickey Cohen, In My Own Words, Prentice-Hall, 1975, pp. 91–92. [12] Gary Wean, There’s a Fish in the Courthouse, Casitas, 1987, quoted by Michael Collins Piper, Final Judgment:

The Missing Link in the JFK Assassination Conspiracy, American Free Press, 6th ed., 2005, pp. 290–297. [13] Alfred Lilienthal, What Price Israel? (1953), Infinity Publishing, 2003, p. 50. _________________________________________________________________________

The Case of James Forrestal and the Take Downs of Real America Firsters

‘I am more and more impressed

by the fact that it is largely futile to get up and make statements about current problems. At the same time, I know that

silent acquiescence to evil is also out of the question.’ –– Thomas Merton (1915 – 1968) More

than occasionally, top-ranking Americans who are not Israel Firsters are taken out. It seems the preferred method to get

rid of the “uncooperative” is a character assassination. Case in point was Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, who was

slated to become President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Defense in 1994. Inman’s downfall followed his comments

such as this: “Israeli spies have done

more harm and have damaged the United States more than the intelligence agents of all other countries on earth combined

… They are the gravest threat to our national security.”

This article explains how the neocon Zionist media operatives got Inman to withdraw and go home by calling him a “conspiracy theorist”

and a kook. This was spearheaded by The New York Times (aka New York Slimes) Jewish columnist William

Safire. It is generally believed that he was also threatened. Later in 2006, Inman was further marginalized by the usual

suspects for criticizing the Bush administration’s use of warrantless domestic wiretaps. Admiral Inman at least escaped with his life. Perhaps the most well-known America Firster

to meet a suspicious fate was James Forrestal. His 1944-1949 diaries were published in 1951; they are insightful, coming from an powerful insider. He was U.S. Navy Under Secretary from 1940 and Secretary

for Defense from 1947 to 1949. After the war, Forrestal urged

Truman to take a hard line with the Soviets over Poland. He also strongly influenced the new Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy concerning infiltration of the government by Communists. In McCarthy’s words, “Before meeting with Jim

Forrestal, I thought we were losing to international Communism because of incompetence and stupidity on the part of our

planners. I mentioned that to Forrestal. I shall forever remember his answer. He said, “McCarthy, consistency has never

been a mark of stupidity. If they were merely stupid, they would occasionally make a mistake in our favor.”

Clearly the experienced Forrestal was not buying into the bogus Hanlon’s Razor of “never attribute to malice,

what could be explained by stupidity. During private cabinet

meetings with President Truman in 1946 and 1947, Forrestal favored a federalization plan for Palestine, with which at first

Truman concurred. Truman then received threats to cut off campaign contributions from wealthy donors, as well as hate mail

and an assassination attempt. Appalled by the intensity and implied threats over the partition question, Forrestal

stated to J. Howard McGrath, senator from Rhode Island: “… No group in this country should be permitted to influence our policy to the point it could endanger

our national security.”

I draw your attention

to several revealing Forrestal diary notations: Feb.

3, 1948 (pages 362 and 363): “Visit today from Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., who came in with strong advocacy

of a Jewish State in Palestine, that we should support the United Nations ‘decision,’ I pointed out that the

United Nations had as yet taken no ‘decision,’ that it was only a recommendation of the General Assembly and

that I thought the methods that had been used by people outside of the Executive branch of the government to bring coercion

and duress on other nations in the General Assembly bordered closely onto scandal … I said I was merely directing

my efforts to lifting the question out of politics; that is, to have the two parties agree that they would not compete for

votes on this issue. “He said this was impossible, that the nation was too

far committed and that, furthermore, the Democratic Party would be bound to lose and the Republicans gain by such an agreement.

I said I was forced to repeat to him what I had said to Senator McGrath in response to the latter’s observation that

our failure to go along with the Zionists might lose the states of New York, Pennsylvania and California — that I thought

it was about time that somebody should pay some consideration to whether we might not lose the United States.”

The entry for Feb. 3, 1948, continues (page 364): “Had lunch with Mr. (((B.

M. Baruch))). After lunch raised the same question with him. He took the line of advising me not to be active in this particular

matter, and that I was already identified, to a degree that was not in my own interest, with opposition to the United Nations

policy on Palestine.”

At this time, a campaign of unparalleled slander and calumny

was launched in the United States press and periodicals against Mr. Forrestal. This was led by the notorious rumor and Jewish

gossip monger Walter Winchell and hatchet man, liar and shabbos goy Drew Pearson. In January 1949, Pearson related that Forrestal’s wife had been

the victim of a holdup back in 1937 and falsely suggested that Forrestal had run away, leaving his wife defenseless. On

March 22, 1949, Forrestal resigned as Secretary of Defense. However, he was a wealthy man and was planning on starting a

journalistic endeavor with America First leanings. A few

days later, the claim was made that he “had a nervous breakdown” (denied by Forrestal’s brother). He was

administered narcosis with sodium amytal and a regimen of insulin. According the assigned doctor, the patient “over

reacted” and was “thrown into a confused state with a great deal of agitation and confusion.”  Photo taken of scene at Bethesda. Somehow Forrestalmanaged to pull the window

back down on the way out. Photo taken of scene at Bethesda. Somehow Forrestalmanaged to pull the window

back down on the way out.Ultimately, Forrestal “fell” from

a 16th floor window at Bethesda Naval Hospital. Drew Pearson ran more phony lies that Forrestal had made four “previous”

suicide attempts. Another dubious Jewish “historian,” Arnold Rogow, continued the fictitious account of his death

and character assassination with the well-worn “anti-Semitic nut” and “paranoid conspiracy theorist”

accusation. Rogow’s travesty — I mean “book” — is a case study in lies and hatchet jobs. It can be read here. In 2004, the “Willcutt Report” was finally declassified after 53 years and exposes these fabricators on the particulars of Forrestal’s murder.

If you read through it while thinking critically, the whole scene reeks of skulduggery and story telling. There is also a smoking gun connection in this report. It reveals his “care”

was administered by MK-Ultra psychiatrist Dr. Winfred Overholser, who signed off on the report. This was the operative who

ran the St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. He specialized in “involuntary psychiatry,”

LSD research, truth drugs and was at the center of the mind-control network. St. Elizabeth’s was also where other “sensitive” federal cases were kept during Overholser’s

tenure, such as poet Ezra Pound (illegally committed for Axis and “anti-Semitic” sympathies during WWII) and

John Hinckley, Jr., who shot Ronald Reagan. When he was “committed”

against his wishes, Forrestal was a private citizen and no longer a high government official. By what authority did the

rouge government element take him to Bethesda? Most interesting that during this stage he was surrounded by Zionist Jewish

moles such as Marx Leva. Henry Forrestal tried several times

to see his brother James in the hospital but was refused visiting rights by both Dr. Raines and [acting hospital commandant]

Captain [B. W.] Hogan. He finally managed to see his brother briefly after he had informed Hogan that he intended to go

to the newspapers and after he had threatened legal action against the hospital. Henry Forrestal stated that when he was finally allowed to see his brother, he found James “acting and talking

as sanely and intelligently as any man I’ve ever known.” Henry tried to persuade Dr. Raines to allow Forrestal’s friend and Catholic priest, Father Maurice Sheehy,

to visit. Raines turned Sheehy away on six separate occasions. Despite

the difficulties people close to Forrestal had in gaining access, Zionist minion and water boy Congressman Lyndon Baines

Johnson saw Forrestal in the hospital. Why- to deliver some kind of final threat and message? Forrestal didn’t care

for the man. Two hard headed personalities, Forrestal probably told LBJ to go screw himself. The bottom line on James Forrestal that sealed his sad fate was he was an America Firster

and would have spoken out. If you research his death, you will also come across a ridiculous back story, character assassination,

smears insults, lies and diversions about UFOs, all crafted to make him sound kooky.

Click on this text to listen to Author Dave Martin discuss his book - The Assassination of James Forrestal

______________________________________________________________ Secretary of State James Forrestal’s death was ruled a suicide even though there were signs of a struggle, he was found thrown from a closed window with a cord around his neck and left a suicide

note that was in someone else’s handwriting. _______________________________________________________________________ The Willcutts Report

On the Death of James Forrestal

Here you will find the complete text of the Willcutts Report. First a little background. James

Forrestal was Secretary of the Navy during the last year of World War II. In September 1947, after consolidation of the

Army and Navy, President Truman appointed him Secretary of Defense, the first person to hold that position. Forrestal later

became outspoken in his criticism of certain policies of the Truman administration. We won’t go into the details or

the smear campaign waged against him by Drew Pearson, Walter Winchell and others. Near the end of March 1949 Truman demanded

Forrestal’s resignation, a move Forrestal had anticipated. Forrestal’s

successor was sworn in the morning of March 28. Later the same day Truman presented Forrestal with the Distinguished Service

medal. The next day the House Armed Services Committee held a ceremony lauding Forrestal’s military service, at which

he gave a brief speech. Afterwards, the usual account is that Stuart Symington, Secretary of the Air Force, sought out Forrestal

and talked with him on their ride back to the Pentagon. Marx Leva, Forrestal’s top aide, found Forrestal profoundly

changed after this meeting, preoccupied and absent minded. He informed Forrestal’s friend Ferdinand Eberstadt who then

persuaded Forrestal to go with him to a vacation spot at Hobe Sound, on the east coast of southern Florida, for a rest.

That, to repeat, is the usual account, based on the testimony of Leva among others. But a news article has been discovered

datelined the day of the medal presentation, that is, the previous day, which states that “Forrestal is flying

tomorrow to Hobe Sound, Fla., for a long rest.” Obviously the trip had been planned, by someone or some group, all

along. (See the article “James Forrestal’s ‘Breakdown’ ” under the

David Martin link below.) On March 31 Clifford Swanson, Surgeon General

of the Navy, began proceedings to have Forrestal hospitalized if he so desired. Two days later Forrestal was flown from

Hobe Sound back to Washington and admitted to Bethesda Naval Hospital suffering from what the doctors described as exhaustion

and depression due to overwork. He was placed on the 16th floor of the

central tower in a suite with a small kitchen. By all accounts after a few weeks rest he had recovered, yet he was not released.

Seven and a half weeks later, on May 22 a few minutes before 2 a.m., he went out the kitchen window, landing on a roof 13

floors below with a bathrobe cord knotted around his neck. A military

board of investigation “for the purpose of inquiring into and reporting upon the circumstances attending the death

of Mr. James V. Forrestal” was convened on May 23 by Morton D. Willcutts, Rear Admiral of the Navy’s Medical

Corps, with Captain A. A. Marsteller as senior ranking officer. The proceedings lasted five days. The resulting report,

approved July 13, 1949, is now known as the Willcutts Report. The Navy never published the report in full and it remained

filed away and forgotten until April 2004, when David Martin discovered it using a Freedom of Information Act request. A PDF photocopy is at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library of Princeton University. The

HTML rendition of the Willcutts Report presented here has several advantages over the photocopy. It is much easier to read,

your browser can find desired text instantly, Google can better index it, and you can easily and accurately quote the report

using copy-paste. The ability to search will be especially useful since the report is a mass of unorganized detail. Even a cursory reading of the report reveals that books about Forrestal seriously

misrepresent what happened the evening of May 21st 1949. David Martin, who has made a specialty of exposing the chicanery

of what he calls court historians and journalists, analyzes this in detail in his series of articles cited above. Forrestal

has been called crazy, yet you will search the report in vain for such words as delusion, persecution, anxiety, paranoia. The report begins rather boringly with 27 pages of official approvals, statements

and endorsements. The meat is the Proceedings section, a transcript of witness testimony starting on photocopy page 28. This

section’s pages are numbered 1 to 61 in the report, which are pages 28 to 88 of the photocopy. Then follows an untitled

review of the evidence, and lastly an appendix of exhibits (including the most revealing Nurse’s Notes). The first

27 pages of the report – numbered 1 to 27 in the photocopy – are not part of the report proper, though it’s

usually convenient to refer to everything as simply “the report.” It

is provided below uninterrupted by comment (except for bracketed notes on textual lapses) but a few remarks must be made

at the outset. Forrestal had long antagonized two groups known for assassinating their opponents: communists and zionists.

Any investigation of his death worthy of the name would have considered the very real possibility he had been murdered,

“suicided” as the expression goes, yet this possibility is never explicitly raised in the report. The board members

and the witnesses they call all seem to take for granted that Forrestal killed himself. The questions asked focus on one

issue: Was anyone in the Naval Medical Corps responsible? The report is far from the very thorough inquiry it claims to

be. When in the report you read about providing Forrestal “security”

it always means protecting him from himself, never from an outside threat. That he might have needed the latter kind of

protection apparently never occurred to the hospital administration. Everyone

in the Medical Corps who dealt with Forrestal before his death seems worried about getting charged with incompetence. Their

worry is understandable since they were responsible for preventing patients in the neuropsychiatric ward from injuring themselves.

If Forrestal had to die, better for their reputation had it not been by suicide. If Forrestal had to die an unnatural death,

better had it been murder. Thus the investigative board’s failure to consider the possibility of murder, given that

it was a possibility, is all the more puzzling. Their naïveté, if such it was, was not in the Medical

Corps’ interest. In spite of ignoring the murder angle, the board

never states flat out that the death was suicide, either. Winfred Overholser’s statement (photocopy page 2) is his

opinion of the report rather than part of the report itself. In particular, he says: “From a study of the report, it

is my opinion that Mr. James V. Forrestal came to his death by suicide while in a state of mental depression.” This

is a gratuitous remark since the report, despite it insinuating suicide, reaches no conclusion regarding the ultimate cause

of Forrestal’s death. It simply does not address the question. Neither of its two “Finding of Facts” sections

(page 22 and page 88) mentions suicide, and its untitled review of evidence (page 89) states only that the hospital psychologists

considered him a potential suicide and that they took a calculated risk, and then abruptly – too abruptly –

ends. Reading the transcript of witnesses, some pompous, some naïve,

many apprehensive they will be charged with negligence, the impression gradually builds of a silent presence lurking over

the proceedings: the ghost of unasked questions.

Things to Look for while

Reading the Report First of all, the report is worth reading. World War II and its immediate aftermath was a turning point

in U.S. history which led to where we are today, and only a re-evaluation of that period can save us. If Forrestal, an outspoken

critic both of Soviet fellow travelers and of bringing the Arab-Israeli conflict into domestic politics, was indeed silenced

by an assassin, it is an important piece of history we need to know more about. The Willcutts Report provides evidence in

the case, much of it without intending to. The main thing to observe while reading the report is that besides being inconclusive regarding the cause

of death the investigation was amazingly incomplete. The Medical Corps, its recorder and review board, again and again fail

to consider obviously pertinent lines of inquiry. You can see the failure by considering the report alone, as if it were

your only source of information about the case, and then you can see further omissions by examining other sources. Here are some questions and observations that might occur to anyone while reading

the report. You can click the small square buttons (  ) to jump to an appropriate point in the Proceedings testimony. Click

your browser’s back button, or press Backspace or Alt left-arrow , to return

to where you were. (You can just ignore the small square buttons on first reading.) ) to jump to an appropriate point in the Proceedings testimony. Click

your browser’s back button, or press Backspace or Alt left-arrow , to return

to where you were. (You can just ignore the small square buttons on first reading.) Why would a man, angry that a newspaper

columnist he despised had called him crazy, then prove it by leaping out a 16th story window?

The psychiatrist George Raines emphasizes that

Forrestal was a fast mover, that “he moved like lightning.” (To go outside the world of the report for a moment,

photos of Forrestal while alive show a man who carried himself exceptionally well. Such people are graceful, efficient in

their movement.) Then Raines takes the ability to move rapidly to mean acting on impulse. But agility is not carelessness

or impetuosity, they are completely different attributes. Agility is a positive quality and doesn’t entail anything

negative.

Even by April 9 Forrestal was doing well. The

following is from the Nurse’s Notes of that evening, photocopy pages 47 and 48 (exhibit 3 items #57 and #58).  April 10, Hour 14:30 (original all in caps, some punctuation added here): “Pt. woke up. Struck up conversation

with corpsman by saying ‘Prise, you must begin to regard your patients as animals in a zoo after a while.’ When

I told him I didn’t he smiled and said ‘That’s good.’ ” Hour

16:00, after a visitor: “... Pt. in very good mood.” April 10, Hour 14:30 (original all in caps, some punctuation added here): “Pt. woke up. Struck up conversation

with corpsman by saying ‘Prise, you must begin to regard your patients as animals in a zoo after a while.’ When

I told him I didn’t he smiled and said ‘That’s good.’ ” Hour

16:00, after a visitor: “... Pt. in very good mood.”

On

May 20th and again the 21st, the night Forrestal was to fall to his death an hour or two after midnight, a new man was assigned

to the third shift watch.  Why didn’t the board call the earlier third shift watch, C. F. Stuthers Why didn’t the board call the earlier third shift watch, C. F. Stuthers  , to testify so that he could be asked what he usually did and experienced on duty, and compare it with what his replacement

did and experienced? , to testify so that he could be asked what he usually did and experienced on duty, and compare it with what his replacement

did and experienced?

What was the background

of that replacement, Robert Wayne Harrison, who as it turns out had been assigned to the hospital only a week or so before

steps were taken to admit Forrestal?

For that matter, what was the background of

everyone at the hospital who could possibly have accessed Forrestal the night of May 21st?

It is easy to get the impression from the report that there were no other patients on the 16th

floor, that Forrestal had the whole floor all to himself. But surely such an unusual situation would have been explicitly

stated in the report, and it isn’t. Who then were the other patients and when were they admitted? Not only were these

patients worth questioning because one of them might have seen or heard something unusual, what better way for an assassin

to gain access to the floor than as a fake patient?

Common

sense if not common or military law dictates that an unnatural death be presumed a potential homicide until proved otherwise.

Why wasn’t at least one professional criminal investigator on the board of inquiry? An admiral may have executive

ability and still be a fool when it comes to conducting a criminal investigation. The entertaining fraud Uri Geller fooled

many a Ph.D. yet was quickly exposed by James Randi, a theatrical magician who knew the trickster business. When it came

to investigating a homicide the board was no place for amateurs.

That

said, at times it seems that only duplicity could account for the board’s otherwise inexplicable lack of curiosity.

Look at the photographs of Forrestal’s bedroom,

exhibits 2H, 2J and 2K – especially 2K.  A man lived in that room for seven weeks, has just met a death as unexpected as it was violent, and his bedroom looks like

something out of Hotel Beautiful. Forrestal’s suite should have been treated as a crime scene, yet obviously

someone had cleaned up before this photographic record was made. Nurse Dorothy Turner, who saw the room minutes after Forrestal’s

death, describes slippers on the floor and a bed whose sheets are turned back. A man lived in that room for seven weeks, has just met a death as unexpected as it was violent, and his bedroom looks like

something out of Hotel Beautiful. Forrestal’s suite should have been treated as a crime scene, yet obviously

someone had cleaned up before this photographic record was made. Nurse Dorothy Turner, who saw the room minutes after Forrestal’s

death, describes slippers on the floor and a bed whose sheets are turned back.  Who ordered the cleanup and why? The review board called one of at least two photographers as witness. He fails to say

when he took his pictures and the board does not ask. Who ordered the cleanup and why? The review board called one of at least two photographers as witness. He fails to say

when he took his pictures and the board does not ask.  Judging from sunlight streaming through the windows in the report exhibit pictures, they were taken several hours into

the day. Why weren’t pictures taken about the same time as those of Forrestal’s body, soon after his fall, Judging from sunlight streaming through the windows in the report exhibit pictures, they were taken several hours into

the day. Why weren’t pictures taken about the same time as those of Forrestal’s body, soon after his fall,  or if there were where are they? or if there were where are they?

At one point

the board asks nurse Dorothy Turner: “You said you saw [Forrestal’s] slippers and a razor blade beside them;

where did you see them?” Yet in the proceedings as transcribed in the report she had not mentioned seeing

slippers, indeed no one had mentioned any slippers before this. She answers the question as if nothing were wrong with it.

Before the question alluded to above, Dorothy

Turner had said she saw broken glass on the bed right after Forrestal was missed.  The board ignores the broken glass, and fails to ask the obvious question: Were there signs of a struggle? For surely broken

glass suggests this. In earlier testimony a photographer showed pictures of broken glass on the rug – taken he said

about an hour after Forrestal’s death, though the picture put in the report may have been taken later – so the

board members had had time to think about this evidence. The board ignores the broken glass, and fails to ask the obvious question: Were there signs of a struggle? For surely broken

glass suggests this. In earlier testimony a photographer showed pictures of broken glass on the rug – taken he said

about an hour after Forrestal’s death, though the picture put in the report may have been taken later – so the

board members had had time to think about this evidence.

How long was the bathrobe cord found tied around

Forrestal’s neck? (This information may be in exhibit 4, which is missing from the released report, but such an important

detail should have been brought out in testimony as well.) What evidence was there, if any, that the cord had been tied

to something else too, as insinuated by Raines?  We are told the cord was unbroken. We are told the cord was unbroken.  How could an intelligent man fail to securely tie a knot that many a six year old knows? What were the cord lengths to