|

|

. .

Click on this text to visit the SIR OSWALD MOSLEY website...  Click on this text to view a Sir Oswald Mosley | Interview | Thames Television | 1975 ... . . Click on this text to listen to Mosely's book TOMORROW WE LIVE (audio book) Sir Oswald Mosley: Briton, Fascist, European

Late in 1932, about a year after the financial crisis that rocked Britain to its foundations and heralded the great depression of the thirties, George Bernard Shaw said at a Fabian meeting in London: "You may remember the eloquence with which Mr. Ramsay MacDonald begged the nation to defend the gold standard.

(The Journal of Historical Review)

They all rallied 'round the gold standard and gave Mr. MacDonald a big majority. They were told that as long as they stuck to the gold standard the trade of England was safe." Yet "Mr. MacDonald, who had been hailed as the man who saved the nation by keeping it on the gold standard, was then hailed as the man who saved the nation by taking it off the gold standard."

Thus the ironic Shaw on that extraordinary sleight-of-hand by which the old political order faced the crisis of 1931.

He then turned to MacDonald's leading critic who had warned, in vain, that the crisis was coming. "You will hear more of Sir Oswald Mosley before you are very much older. I know you dislike him, because he looks like a man who has some physical courage and is going to do something, and that is a terrible thing. You instinctively hate him, because you do not know where he will land you. Instead of talking 'round and 'round political subjects, and obscuring them with bunk verbiage without even touching them and without understanding them ... he keeps hard flown to the actual situation." So much for what Shaw really thought of his Fabian friends, many of whom were to rise to the very heights of "the Establishment," those rulers who have run Britain down-hill since 1931, Mosley's entrenched opponents all his life.

Others, too, were to recognize the same attitude in high places. Richard Crossman wrote in 1961 that "Mosley was spurned by Whitehall, Fleet Street and every party leader at Westminster simply and solely because he was right." No doubt, as Crossman added, he was spurned because he "was prepared to discard the orthodoxies of democratic politics and to break with the bankers of high finance in order to conquer unemployment," a terrible thing in the view of Shaw, ironic as ever. Dazzled by Mosley's "brightly shining star," as Michael Foot observed in 1968, the men of the Establishment decided they preferred, after all, "mediocrity and safety first which consigned political genius to the wilderness and the nation to the valley of the shadow of death" and to much suffering in large parts of Britain during the unemployment of the thirties.

Mosley, in the opinion of Lord Boothby and others, could have been "a very great Prime Minister" leading either a Labour or a Conservative government. That was not to be. Mediocrity ruled in Britain instead.

Who was this man Mosley? The noted historian A.J.P. Taylor wrote in 1965 that "his proposals were more creative than those of Lloyd George and offered a blueprint for most of the constructive advances in economic policy to the present day... evidence of a superlative talent." David Lloyd George himself saw Mosley as a man of "remarkable lucidity and force." John Wheatley, M.P. of "Red" Clydeside, said in 1926 that he was "one of the greatest and most hopeful figures the socialist movement has thrown up." Colonel Joseph Wedgwood of the Labour Party, later a Father of the House, said after Mosley's speech of resignation from government in 1930: "I watched the Liberal Party. I watched the Conservative Party. Man after man was saying to himself: 'That is our leader.' "

Such were the views of leading historians and parliamentarians. Great audiences thought likewise, when they heard his policies. During the stormy General Election of 1931, as New Party meetings up and down the country were being wrecked by organized mobs, Mosley held one remarkable meeting in Manchester's Free Trade Hall about which the Manchester Guardian was to say: "In his thirty-fifth year Oswald Mosley is already encrusted with legend... Who could doubt when he sat down after his speech on Saturday, and the audience, stirred as an audience rarely is, rose and swept a storm of applause towards the platform -- who could doubt that here was one of those root- and-branch men who have been thrown up from time to time in the religious, political and business story of England? His ideas swept a great audience off its feet and the scene at the end was matter for thought to any 'elder statesman.' "

In the world of letters Beverley Nichols was later to write in his News of England in 1938, the time of the British Union of Fascists (BUF): "For Mosley, whether you regard him as a limb of Satan or a potential saviour of this nation, is one of the three most dynamic personalities in the Empire today. And the men he has inspired are animated by something akin to a religious faith."

How did the man regard himself? He wished to be known to posterity as "the man of synthesis," and in a recent criticism in the Times Higher Education Supplement, Richard Thurlow conceded he had "a brilliant synthesising mind... He synthesised many of the best ideas of his time: Keynes's critique of the Establishment's deflationary policies, Lloyd George's great public works to soak up unemployment, Joseph Chamberlain's demand for an insulated home market and protection for the British Empire, and C.H. Douglas's proposals of consumer credits to raise the purchasing power of the poorer sections of the community."

There was also guild socialism. Mosley wrote in his autobiography, My Life: "My inclination in British politics was always towards the guild socialists -- then represented by such thinkers and writers as [G.D.H.] Cole, [J.A.] Hobson and [A.R.] Orage -- rather than to state socialism, whose exponents were the Webbs and the Fabians. The tradition of the mediaeval guilds in England, of the Hanseatic League and the syndicalism of the Latin countries was much nearer to my thinking." At the same time he could appreciate the power of the Federal Reserve System and what he saw of American mass production methods during his visit to the United States in the twenties, reaching yet another synthesis for Britain by combining what he learned in America, the most advanced capitalist state, and the thinking of British guild socialists and European syndicalists.

Yet he was more. He achieved his own personal ideal of the "complete man" of politics, economic thinking, war service in 1914-18, a man of culture with a deep interest in philosophy, the true aristocrat who was "the friend of the people." And there was his sport. Descended from a family long connected with the land of England, including a grandfather famous for his pedigree cattle and the very model for England's "John Bull," Mosley's early interest in sport turned to boxing, "The Fancy" of his ancestors in a more robust age. He also represented his country in international fencing contests in his thirties.

"He is very English," wrote James Drennan of the Mosley of that time, "as it were, a composite ghost of English history, yet his enemies complain he is so 'un-English.' Perhaps they mean that he lacks that bourgeois stamp which has moulded to its flaccid type the generations of English politicians who have grown up since the Industrial Revolution. There is something of the Elizabethan in his gallant, rather arrogant air. He is the Englishman of the Carolean tennis court, of the duelling ground rather than of the Pall Mall club. Then again, with his boxing and fencing, he has walked in the tradition of the Regency 'buck' in a time when people have got into the habit of expecting younger politicians to have horn-rimmed spectacles and soft white hands. He is a big man of blood and bone, of strong tones, no feeble creature of grey shadings. He is a personality, with all his individual qualities and faults, no self-complacent bladder of conventions."

A certain hard seriousness and a natural chivalry were indeed his hallmarks. Several times in later life he was in a position to destroy an opponent by exposing personal scandal. "We must confine our attacks on these people to their public lapses and not to their private lives, however disgusting" was his invariable response.

The Mosley story began in the waterlogged trenches of Flanders, red with poppies and the life blood of a slaughtered British generation, and in the Royal Flying Corps where he learned to respect his opponents, the young German airmen of 1914-18, feeling a kinship with them higher than his regard for "the old politicians who sent both of us there, to fight." Many years later he saw a film of the Verdun battles when he experienced an immediate spiritual comradeship with one French soldier silent and stark amid that enormous suffering.

Out of these deep impressions of what G.K. Chesterton described as "that awful depopulation" of Europe, there sprang his lasting faith in an ultimate union of the nations of Europe to end all conflicts of brother peoples.

And so, with the limp which was his own personal legacy from the trenches, he went into Parliament with a hatred of world wars to raise his great voice for "the missing generation," his mission that never again should there be another such bloodbath. Winning Harrow for the Conservatives in the "Khaki Election" of 1918, he was asked to explain his policies. His reply, in the tradition of Joseph Chamberlain, was "socialist imperialism"; he had fought on a platform of high wages and shorter hours, housing schemes carried out by the nation, the abolition of slums, and health and child welfare policies.

But when he reached Parliament, as he later said, "the first shock was the sight of my colleagues. The young men were in a minority and the 'hardfaced men' were in a great majority. The profiteer outnumbered the fighter." Thus when those "hard-faced men" who then led the Conservatives betrayed the war-time pledge that a land for heroes would be built after so much sacrifice, while disgracing themselves during the Black and Tan period in Ireland, he left that party.

For a time he sat in Parliament as an Independent, holding Harrow against the attacks of Conservative press and party machine in two further elections, and there he was spotted as a coming man by the bright eye of the Labour leader, Ramsay MacDonald, to be invited to join that "peoples' party" which MacDonald in turn was to betray, in 1931. In 1924, when Mosley joined Labour, Britain was in the grip of a merciless deflation. Other hard-faced men in high places, the Cunliffe Committee of City bankers and Treasury officials, had met in conclave before the killing was over in 1918 and there decreed that deflation was the essential road "back to normality" after the war. This was accepted widely. By 1925 Stanley Baldwin, Tory leader, was stating bluntly that "all the workers in this country have got to face a reduction in wages." The Liberals were split on the question, but they were the declining party. Even Labour, the rising party, no matter how much it denounced deflation in opposition, was led by men who tugged their forelocks to the bankers in office. Prominent among them was the mercantilist Philip Snowden. He announced shortly after becoming Chancellor in the first Labour government of 1924 that he was "much guided" by the findings of the Cunliffe Committee. As Chancellor again in the second Labour government he was to say in 1931 that "the City would not stand for" Mosley's proposals for solving unemployment.

The latter did not join a party widely proclaiming its "socialist" goal in order to grovel in this way before the power of high finance. All his sympathies lay with the guild socialist tradition in that party, all his ideas were opposed to the deflation demanded by the Establishment of the day. His years of synthesizing then began, seeing much of Keynes -- at that time the leading rebel against the Cunliffe Committee's dictates -- and inevitably coming into growing conflict with the Snowdenites; for such leaders, cast in an older mold, Mosley had far too many ideas and most of them dangerous.

By 1925 he had written Revolution by Reason, a book revolutionary in the sense that it cut across the current orthodoxy and proposed the deliberate raising of living standards through consumer credits, injecting purchasing power wherever it was needed most in order to match the greater power of industry to produce. And in these proposals lay the origins of that later breach with Labour leaders.

For, while Mosley campaigned for higher living standards at public meetings where he was increasingly in demand, a Conservative government took measures to depress those standards through a more rigorous deflation than Mrs. Thatcher recently has attempted -- and there on the Labour front bench in Parliament the Snowdenites bowed in deepest reverence to the financial gods sacred to Stanley Baldwin, Tory leader. The men of like minds occupied both front benches. The men who wanted change sat behind, with Mosley.

Incredible though it may seem to much opinion in the 1980s, Mosley did not turn to Fascism because of "arrogance" or "ambition" but simply because he soon came to realize that socialism would not be built under the old leadership; the logic of his ideas drew him ever more towards a form of proto-fascism but for the word itself. For him this arose from the memory of comradeship in the trenches, uniting all classes in face of the machine-guns which struck down all irrespective of social class. It arose from his "socialist imperialism"; its dynamic thrust came from his synthesis of economic ideas; its method of government was inspired by Lloyd George's inner cabinet, a government of action which had won the war of 1914-18 and which Mosley would transform into "a machinery of government" to solve the problems left by that war.

First among those problems was unemployment. This continued to rise rapidly despite the election of a Labour government in 1929 to solve it. Seeing that MacDonald's speeches on the subject were having no effect, Mosley compiled his own policies of action in the famous "Mosley Memorandum" of early 1930; a government determined to solve unemployment, equipped with the machinery to do it, was the vital part of his proposals.

Yet when placed before the men of the Cabinet, these proposals aroused their pious horror, for the men were paragons of inaction, dedicated to muddling through. Close contact with their woolly minds had no doubt made a parting of the ways likely in any event: this was made inevitable by their limp response to the approaching crisis and the inertia with which they answered Mosley's dynamism. When they rejected the Memorandum, while refusing to produce something better themselves, he resigned from the Labour government in May 1930.

Father Brocard Sewell of the Carmellites, replying to an obituary in Mosley's old school magazine, The Wykehamist, wrote that "when the dust has settled" Mosley may be remembered most for his rejected Memorandum, which would have solved unemployment, and for his advocacy of a united Europe. Prophetic words.

Much has been written about the failure of Mosley's New Party, hastily formed under the storm cloud of crisis, lacking a press but attacked by the national press, accused of the blackest treachery by former allies, its meetings smashed by the Labour mobs and the communists. Its electoral organization was rudimentary and in the panic conditions of the General Election of 1931 it was swept away.

Those panic conditions, with the workless queues lengthening ominously, set the scene for one of the great confidence tricks of British history. Assisted by some Liberals, the Labour and Conservative leaders united to stampede the country into giving them office again -- although they were the men most responsible for the crisis! They had the support of a servile press which both whipped up the crisis and bamboozled the public. The first step in the charade was taken by MacDonald when his coalition was arranged. "All my friends are with me tonight," declared the erstwhile revolutionary as he faced the House of Commons, proudly surveying his former class enemies, the leading Tories sitting poker-faced at his side. The men of like minds were together at last.

A further step was that trick derided by Shaw before the dumbfounded Fabians, the trick of panicking the country into defense of the gold standard to be duly followed by the abandoning of the gold standard, yet still to the applause of the servile press.

Hence the bitterness of Mosley, who had striven to arouse a Labour government to action long before the crisis arose, at the one-time visionaries of "socialism" joining in the trickery which thus resuscitated the economic system they had spent their lives in denouncing. The defeated New Party had offered a real alternative to that system and had been at least an attempt to save Britain from the mass unemployment that followed in the thirties, and in the last issue of its paper, Action, Mosley flung his defiance at his triumphant opponents: "Better far the great adventure, better the great attempt for England's sake, better defeat, disaster, better far the end of that trivial thing called a political career than stifling in a uniform of Blue and Gold, strutting and posturing on the stage of Little England, amid the scenery of decadence ..."

And for those who stood fast, unlike those who had broken at the sight of the mobs or had chosen "safety first" in the ranks of the old parties after all, he reaffirmed the original faith which had taken him into politics: "Before we go we will do something great for England. Through and beyond the failure of men and parties, we of the war generation are marching on, and we shall march on until our end is achieved and our sacrifice atoned." It was to be a stormy road.

Oswald Mosley was bitterly condemned when he took the road to Fascism. Critics were as outraged then as they have been since. Suddenly they began to notice certain flaws of character which had not been apparent when they praised his abilities.

Yet this recoil from men who dare to cross Rubicons and defy the fates has occurred again and again in history.

History also shows that all new ideas, as Fascism was new in Britain in 1932, have met with strong opposition in that country from their inception. Parliament itself was not a British invention but was imported from France by Simon de Montfort in the very teeth of opposition from the mediaeval crown. Democracy in classical times originated in Athens, and in modern times again in France: great thunderings greeted it from the great landed interests when its early crude form emerged during the French Revolution. England went to war with democracy then, a conflict intensified when Napoleon Bonaparte, its military champion, reached power in France. And England and Prussia, defenders of the older order, defeated Napoleon and democracy at Waterloo in 1815. Nevertheless democracy was to triumph in the end in England, through a series of political changes beginning with the first Reform Act of 1832, eleven years after the great Napoleon died, and to such an extent that in the more spacious Victorian age English statesmen came to pride themselves as the very paladins of democracy: Read their speeches.

Thus just a hundred years after the passing of the Reform Act, when Britain was long settled in democratic ways, the founding of the British Union of Fascists aroused another storm in 1932.

What was Fascism? Serious critics now agree that it took several very different forms between the two world wars. Fascism was an intensely national idea and differing national characters and conditions produced different forms of it. Certainly this was true of Mosley's BUF. As he patiently explained to his raging critics, all the political ideas of history had come to Britain from abroad, but it was the true genius of the British people which created the finest examples of those ideas here in this country. So it was with Fascism.

Mosley's Fascism was unique, above all, because of the fact that its main policies rested upon the concept of a united British Empire, and many of its older members had seen service in that Empire. All other Fascist ideas lacked such a wide living space. Again, its national ideology sprang from native British roots, as Mosley's slogan "Britain First" emphasized, and mainly those roots were the earlier ideas of Joseph Chamberlain, Keynes, and Lloyd George, and the guild socialists led by Hobson, Cole and Orage, British every one. What had happened was that Mosley had synthesized their ideas into the British policies of the BUF. He was preeminently "the man of synthesis."

Yet patient explanation and the sheer logic of his standpoint only drew uproar from the critics, chief of whom were in the Labour Party. How ironic it was, therefore, that many of the ideas in The Greater Britain, Mosley's book which launched the BUF, had won him huge support while he was in that party. So popular were these that his vote at the Labour annual conference at Llandudno in 1930 came near to dethroning MacDonald, that grand old man of straw. A few weeks later the same proposals formed a manifesto signed by 17 Labour M.P.s, from Oswald and Cynthia Mosley to Aneurin Bevan and John McGovern, and the famous miners' leader A.J. Cook.

Was there, perhaps, a deep guilt complex at work in the tirades of Labour leaders when the BUF arose?

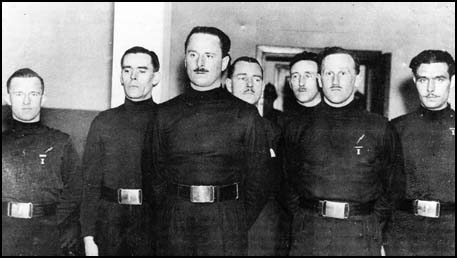

What, however, of the "political uniform" which most enraged them? As far as Mosley himself was concerned the black shirt was adopted for reasons of a hard necessity. It was the means of keeping order at the early meetings when Red violence was mobilized again in a fresh bid to drive him right out of political life. His New Party meetings had been wrecked when the stewards wore no uniform (for instance at the Rag Market in Birmingham), but BUF meetings were not wrecked because the stewards wore the distinctive black shirt; that was the acid test.

Let it be stated clearly that it was the violence of the Left which created the black shirt uniform. Of all the political forces of the time, the violence was mainly responsible for the black shirt's appearance on British streets.

However, what Mosley called "the great negation" of the Left brought forth in reply the great positivism of the BUF through the clash of ideas, a nation-wide movement which wore its political symbol with pride and with heroism in many hard battles to secure freedom of speech for a new idea, uniting all classes in a creed "akin to a religious faith," as Beverley Nichols wrote. Until the old parties, alarmed at this phenomenon which had arisen out of the streets scarred with poverty and depression in the thirties to challenge the corruption of their failure and misrule, used the pretext of yet another wave of Red violence to ban all political uniforms under the grotesquely mis-styled Public Order Act.

Yet the whole question of political ideas has been distorted to an hilarious extent. Almost all political ideas went into uniform during the thirties. Some Social Crediters wore a green shirt uniform. The communists sported the red shirt, seen in London and Red Madrid alike during the decade. Even the democratic parties affected an easily recognized uniform of sorts, the top hat and morning suit of Mr. Baldwin, at least on ceremonial occasions. This became the accepted garb of plump veterans or aspiring younger politicians. From the assembled top hats who had signed the Versailles Treaty down to the British Chancellor on Budget Day they invariably appeared in their own political uniform. It was to be seen in its greatest glory when the League of Nations assembled at Geneva, all dressed like Baldwin no matter what their nationality.

The fact of the matter between the two world wars was that it was the age of political uniforms. Mosley's black shirt was one of many. He had a political uniform, and so had the others.

Yet still the myths persist, and one of the most ludicrous is that the BUF, after a promising start, began to fail in the mid-thirties.

A critic like R.C Thurlow, for example, traces this to "the relative success of the national government in partially reconstructing the economy" after the crisis of 1931. Here a comparison with the National Socialists in Germany can be drawn. They came to power, it is widely agreed, because unemployment in that country more than doubled between 1930 and 1933. Would Hitler have become the Chancellor of Germany but for economic catastrophe? In Britain, on the other hand, unemployment was halved between 1932 and 1939, and yet in those seven years the BUF advanced in strength from fifty members at the beginning to the 30,000 enthusiastic people who packed the Earls Court exhibition hall for Mosley's greatest meeting, just six weeks before war began in 1939.

This was the largest indoor political rally then held anywhere in the world. Nor did any rival organization in Britain attempt such a meeting. And Mosley had been speaking to capacity meetings elsewhere in Britain during the previous two years, notably in Manchester's Free Trade Hall. The ban on the black shirt made no difference, except that his meetings were bigger.

Social collapse brought the National Socialists to power in Germany. Social improvement, "partial reconstruction," the creation of jobs with belated rearmament and a rising war fever against Fascism abroad failed to stop the advance of the BUF in Britain.

But in September 1939 the iron door of war clanged down again monstrously and the second world conflict Mosley had striven to avert tore Europe apart.

This time there would be fifty million corpses piled across the earth, to stare at the "peace makers" of twenty years before at Versailles, and from democracy's laboratories would emerge a new devil's weapon, the nuclear bomb, to raise a hideous question mark high above the earth. If Mosley's struggle for peace ended in 1939, if indeed he was then the "brilliant failure" of the obituary notices, he did not have to run the gauntlet of those fifty million unnecessary dead when his time came to leave this earth and face another verdict beyond. But what of the politicians who took Britain to war?

For three years before the war, and again at Earls Court, Mosley had advanced the way of averting a conflict. The World Alternative, published in 1936, urged a reconciliation of the rising war camps through a settlement of territorial problems created at Versailles. Each of the main nations of Europe would have had a clearly defined political area, with adequate space to solve its problems. For Britain this would have brought freedom from non-British quarrels, enabling the country to devote its statesmanship, effort and wealth to its true interest, the development of the British Empire, whose immense and untapped resources made possible far higher living standards for its peoples.

The official De La Warr Report of early 1939 stated that there were then 100 million people in the Empire suffering from "malnutrition" (i.e., semi-starvation), quite apart from the same problem among hundreds of thousands of the long-term unemployed in Britain. A world slump created this problem. Mosley's policies would have solved it. Britain went to war instead.

Further, the ideas in The World Alternative would have led to a very different union of Europe from that of the postwar (1957) Treaty of Rome, a union into which Britain could have entered much stronger, at the head of the Empire. It was above all a plan for preserving world peace, inspired by the ideals of 1918. Mosley wrote then: "We must return to the fundamental concept of European union which animated the war generation of 1918," and he looked forward to "the union of Europe within the universalism of the Modern Movement."

Was it thus so strange that, after a disastrous war -- that great clash between Fascism and a democracy allied with communism -- he declared in 1948 for the future "Europe a Nation" to achieve a European universalism at a higher level and (ever "the man of synthesis," rising above that clash) turned to "the idea which is beyond both fascism and democracy"?

Meanwhile, during the thirties, his policy was "mind Britain's business," and Britain's business was the preservation of peace and the security of Empire. To secure the Empire he called, in The Greater Britain of 1932 and at the Olympia meeting in 1934, for adequate defenses. He was thus several years ahead of Churchill in demanding rearmament, but with a difference.

While Mosley stood for rearmament to mind Britain's business, Churchill wanted rearmament to interfere in other countries' business.

Churchill was full of the doctrine of the balance of power, which had ruled British attitudes for centuries. His ancestor Marlborough had fought the French over the balance of power, and Churchill fought Germans for the same reason. Though a prolific writer of history, he failed to appreciate that the world had changed since the days of Queen Anne. Certainly Marlborough understood his own age: his battles restored the balance of power in Europe and his genius had made Britain a first-rate power of the day. Churchill's war policy, on the other hand, reduced Britain to a second-rate power and replaced the former European balance of power with a more ominous balance of nuclear terror in the world. This he did by pursuing his demand for the unconditional surrender of Germany, ignoring the postwar consequences of that defeat. Further, he prolonged and enlarged the war to the stage where two extra-European superpowers, the U.S.A. and the USSR, began to dominate the whole course of the war and indeed changed the very shape of the postwar world. Once Roosevelt and Stalin, in command of bigger resources of manpower and material than Churchill, assumed the direction of the war for their own objectives, which were not Britains's, Churchill's voice in their higher councils counted for less and less.

The fact is that Churchill destroyed Britain as a first-rate power, and no amount of nostalgia which surrounds his name can alter that fact.

The point where Britain became a second-rate power in effect (not realized, however, at the time) can be fixed. It was during the Teheran conference of 1943. Churchill discovered at Teheran that his allies were "ganging up on him" and moreover possessed the power to enforce their demands. It happened again at Yalta in 1945, when Stalin was even more powerful and Roosevelt was a dying man.

It was quite true that Churchill realized in later years what his years of war-time vigor had wrought; nevertheless it was then far too late. The war had brought Russian power half-way across Europe, in the hands of those Bolsheviks whom Churchill had spent much of his life denouncing as the most detestable tyrants. Poland, for whose freedom Britain had declared war, had been swept by Red armies into the sphere of the USSR -- that new version of the monolithic Eurasian empire first set up in the Middle Ages under the Mongol conqueror Genghiz Khan. It seems to be lost on most war historians that Stalin's "iron curtain" of 1945 corresponded roughly with the furthest conquests of the old Mongol centuries before: his horde from Eurasia also watered its horses in the river Oder. Lenin, and more particularly Stalin, simply restored that empire and called it the USSR, and Churchill helped to establish it on formal lines at Yalta. While the original empire broke up when Genghiz Khan died and his sons quarreled over the booty, the sons of Lenin remained united. Today, as Stalin's successors, they possess the most formidable military machine on earth.

It is grimly ironic that the Churchill of the twenties who likened the Bolsheviks to "the heirs of Genghis Khan" was the same Churchill of the forties whose war policies brought the Red armies to the river Oder.

As for Western Europe in 1945, shattered by six years of conflict, faced with a Stalin crushing all opposition behind his sealed-off "Iron Curtain," Churchill was to warn in four major speeches between 1948 and 1955 that its continued independence rested solely on American nuclear weaponry. "Nothing," he told the Conservative annual conference of 1948, "nothing stands today between Europe and complete subjugation to communist tyranny but the atomic bomb in American hands." This situation was the logical outcome of the policies of Churchill himself -- the policies which prolonged a world war until Germany surrendered unconditionally and which extended the new-style Mongol empire to central Europe.

Against such madness Mosley had stood out from September 1939, urging strongly the negotiation of peace in Europe, with Britain and the Empire intact. But when Churchill reached the premiership, one of his first acts was the silencing of Mosley.

It is claimed that Britain went to war for "freedom." Not only Polish freedom but British freedom. "Your freedom is in peril, defend it with all your might" shouted the posters in 1939. What did the word really mean when those like Mosley, who stood for an honorable peace, lost their freedom within nine months of the declaration of war?

Lady Mosley described in the Times of November 1981 what happened under Regulation 18B which gave the government power of arrest without charge or trial, and denied to those arrested any recourse to the Habeas Corpus Act, supposedly one of the historic pillars of British freedom. "My husband and I were arrested in the summer of 1940 at a moment of general panic. All our possessions were searched, safes broken open and so forth. I welcomed this at the time, as I thought it would ensure our early release... Months and then years went by and we remained in prison. As we had not been charged with an offense we were denied the luxury of a trial."

Instead of a trial, Lady Mosley continued, "there was an advisory committee, whose chairman was Norman Birkett, K.C. It was held in camera. He questioned Mosley for sixteen hours, and at the end Mosley asked if he might put a question. It was: 'Is it suggested that if the Germans invaded we should help them in some way?,' to which Birkett replied, 'Sir Oswald, you can put any such idea right out of your head.' In other words I am in prison for having advocated a negotiated peace while Britain and the Empire are intact?' 'Yes' was the reply."

That was the entire point of war-time detention without charge or trial.

How indeed could Mosley be accused of conspiring to help German invaders when he had fought the Germans in the first war, he had called for adequate air defenses in his maiden speech in Parliament in 1919 (at a time when government was cutting Britain's air defenses), he had demanded a well-armed Britain in 1932 on founding the BUF, he had called on BUF members in September 1939 to do their duty if called up for military service, and on 9 May 1940, just fourteen days before his arrest, he had stated in his paper Action: "Stories concerning the invasion of Britain are being circulated. In such an event every member of British Union would be at the disposal of the nation. Every one of us would resist the foreign invader with all that is in us. In such a situation no doubt exists concerning the attitude of British Union."

Considering such a long and patriotic record -- a record better than that of some Labour Ministers in the government which arrested him -- clearly Mosley could not be charged with any treasonable intention to help any invaders, German or otherwise.

The sole reason for his arrest and detention was his political opposition to the war, as Birkett admitted. Yet political opposition to wars had long been an honorable British tradition. Lord Chatham opposed war with the Americans in the eighteenth century. Lloyd George opposed war with the Boers in the nineteenth century. Labour leaders like MacDonald, George Lansbury, Herbert Morrison and Bernard Shaw opposed the first world war, all on political grounds. None of these was imprisoned without charge or trial, but Mosley was.

And such was the malice in high places that he and Lady Mosley might have stayed in prison to the end of the war, but for the rapid deterioration in his health. Deprived of vigorous exercise by confinement, the injured leg which had invalided him out of the Army in the First World War now developed a dangerous phlebitis. Under pressure from an uneasy Churchill, Mr. Home Secretary Morrison (a conscientious objector of 1914-18, the jailer of British ex-soldiers in 1939-45) released him and Lady Mosley towards the end of 1943.

Oswald Mosley came out of prison to a very different Britain from that of 1940. Politicians who had refused to unite the nation for construction in peace-time had now done that to wage a destructive war. He regained some measure of his freedom to see his claims for what a united Britain could do fulfilled -- but to wage war, not peace.

Unemployment had vanished. Huge armies in the field had replaced the queues of the workless, and with the rising tempo of American war production (some of which had gone to Russia to aid its turn-around after the Stalingrad battle) these armies spelled the end of Nazi Germany.

Another end could be foreseen. The days of the British Empire were numbered. The old imperial spirit had been submerged beneath a wave of propaganda for worldwide democracy. Something called "trusteeship" for the overseas territories was in high fashion, the preliminary to pushing even the cannibal islands into Westminster-style democracies in that brave, bright postwar world when Hitler and imperialism were dead. Facing the spread of this doctrine, growing ever more luxurious in the war propaganda hot-house, it is true that the old imperialist Churchill was to growl out his defiance at the Mansion House in November 1942: "I did not become the King's First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire." Yet he had already sold the pass.

Had he not signed in 1941 President Roosevelt's Atlantic Charter, which in real terms meant the break-up of the Empire? Had not the President told his son Elliot that he "meant to make Winston live up to it"? Had not Sir Stafford Cripps been sent to India by Churchill eight months before the Mansion House speech with an offer of independence after the war? In the event the offer was rejected. Indian Congress leaders preferred to wait and see if they could get better terms when the war was over. They got what they wanted from a Labour government in 1947 and the liquidation of the British Empire began.

Thus the war left a world in flux and dissolution. Every nationalist leader in the Empire was to demand the same independence. And peace brought a Britain divided again under strident party banners: the unity of the nation was the first casualty of peace.

Two main facts stood out clearly then

First was the fact of Britain's new second-rate status. It showed in many signs of weakness. Britain went to war as a creditor nation and came out a debtor. Huge assets were sold to pay for the war, yet Britain owed billions to the world at the end of it, mainly as the "sterling balances." American Lend-Lease was cut off abruptly with the defeat of Japan. A big dollar loan was advanced instead, under humiliating conditions despite all the efforts of Keynes. The money was spent by a Labour government in about two years, and the loan's repayment was added to the general indebtedness which has bedeviled Britain's position to this day. Further, inflation gained its first real grip on the nation during the war: the cost of living index doubled between 1939 and 1945. Rationing of essential foodstuffs like sugar lasted as long after the war as during it. And in 1945 the electorate's revulsion against Churchill's war-time rule swept a Labour government into power, ushering in the age of rampant bureaucracy and industrial nationalization. Look at the plight of British Railways today.

The same dismal story was told by A.J.P. Taylor in his English History 1914-1945: "The legacy of the war seemed almost beyond bearing. Great Britain had drawn on the rest of the world to the extent of 4198 million pounds... The British mercantile marine was 30 per cent smaller in June 1945 than it had been at the beginning of the war. Exports were little more than 40 per cent of the pre-war figure. On top of this government expenditure abroad... remained five times as great as pre-war. In 1946, it was calculated, Great Britain would spend abroad 750 million pounds more than she earned... Something like 10 per cent of our pre-war national wealth at home had been destroyed, some by physical destruction, the rest by running down capital assets."

Was it really worth fighting the war which Mosley opposed to produce these lamentable results at home and turn Britain into a second-rate power abroad?

And this second-rate Britain was now compelled to earn its living on uncertain world markets, in place of that first-rate Britain which had enjoyed a measure of Imperial Preference before the war. Labour, triumphant in office, saw the end of the Imperial Preference it had always detested, but now was to issue an urgent official exhortation: "Export -- or die!"

In the event Britain did struggle through, or muddle through, but much less due to Labour's boasted "planning" than to the effect of America's Marshall Plan. World markets revived, thanks to lavish American aid. British exports rose, and for a short time it seemed as if this country would rise on the wave of a favorable position in an otherwise devastated world. Much complacency reigned in Whitehall as they looked across the Channel towards the ruins of the Ruhr, the "knocked-out" German trade rival. This would not last, warned Mosley in his first book written after the war, The Alternative of 1947. Once the former enemy countries Germany and Japan began to compete again on world markets, then Britain's favorable position would decline. Indeed it would soon be a case of "all nations will want to send more exports abroad than before."

He pointed to Japan, which was not a competitor in 1947. When Japan joined in the struggle to export, "the experiences of Lancashire and Yorkshire from Japanese competition in the decade of 1930 will be negligible in comparison." The truth of that warning can be seen today. Not only Britain and the rest of Europe but also America are fulminating over the Japanese export success.

The second main fact for Britain in the postwar world was the heavily armed Soviet power less than 500 miles east of London, which space modern tank armies could cover in a matter of days, and the existence of large communist parties in Western Europe led by men like Pollitt, Thorez and Togliatti, who openly stated that their loyalty to Russia came first in any clash.

American military strength offset the first danger, and the Marshall Plan revived the economic life of Europe, reducing the second. But for that aid both France and Italy might have been overwhelmed by communism.

Mosley paid a warm tribute to the Americans for their aid, but asserted that Europe could not remain a pensioner under their protection. Nor had Britain a real future as Europe's off shore island "going it alone" as the Empire broke up. The war had changed the whole position too drastically. Dean Acheson, America's elder statesman, who from a lofty position in Washington had seen the world change, said about this time that "Britain had lost its old role in the world and had not found another." That was true and Mosley, closer to events, now advanced that new role for Britain, through European union. Before the war he had stood for "Britain first." Now he advocated "Britain first in Europe." Britain must take the leadership of Europe for its role, and by its own example unite the war-torn continent as a political entity as great as America. Europe must unite to shoulder most of its own defense in face of a menacing Russia and to solve its many economic problems.

Yet he went further than those urgent questions. While others looked no further than the Council of Europe (little more than a debating club), Mosley launched the Union Movement early in 1948, to be inspired by the "idea which is beyond both fascism and democracy." He called for "the extension of patriotism" to achieve union in the fullest sense, imbued with an idea higher than fascism and democracy, both of which had become obsolete as the result of the war.

In those years he reached new heights as "the man of synthesis." To the challenge of the ruin of old ideas he returned the answer of a new one. And he saw it as part of an organic process which was part of British history. In Britain, England had been the first to unite under the Saxon heptarchy of the eighth century. Wales was then joined to England, and the United Kingdom rose to a brilliant peak under the half-Welsh House of Tudor. Scotland then joined, to make Great Britain. Now it was time to go further, under the pressure of great dangers, and extend patriotism to the whole of Europe in a continuing organic union.

In October 1948 -- the dangerous year of Stalin's blockade of Berlin -- Mosley spoke to an enthusiastic meeting of East London workers and called for "the making of Europe a Nation." Yet, as he said in later years, making Europe into a nation with its own common government did not make him feel any less an Englishman, and an Englishman of Staffordshire where he was born. All other Europeans, Normans and Bretons, Bavarians and Prussians, Neapolitans and Milanese, would through his idea remain Frenchmen, Germans and Italians, as would Britons remain Britons, yet they would all think and act together as Europeans.

In those later years he also proposed a three-tier order of governments in Europe, each with a different function. In fact this was taking the best part of the old fascism, the corporate state, and the best of the old democracy, creating something higher and finer than either, through yet another synthesis. The corporate state had envisaged the nation like a human body, having a head, with a brain, with all members of the body working together in political harmony. Thus in Mosley's vision of the future nation of Europe the first tier, the head, would be a common government -- freely elected by all Europeans -- for Europe's defense and to organize a single continental economy. The second tier would be national governments for all national questions -- elected as today -- and at the third level many local governments for the regions and small nations like Wales and Scotland. They would have the special task of preserving the wide diversity of Europe's cultural life: regional democracy with a new meaning.

Mosley's concept of Europe thus went much further than the present "European Community" and was a direct contrast with it, replacing the national jealousies and economic rivalry of today's "common market" with an essential harmony. "Europe a Nation" included the whole life of the continent from the head organizing a single economy down to the many cultures of Europe. It was perhaps his greatest concept: a new order of governments giving a new meaning to democracy, to be achieved through a synthesis of those two old opponents, prewar fascism and prewar democracy.

The turbulent year 1950 advanced Mosley's thinking again. The communist threat to Europe had lessened as the Marshall Plan put industry on its feet, Stalin's blockade of Berlin had failed and, in 1949, the NATO alliance had been formed. Yet if communism had been checked in the West it was sweeping everything before it in the East. China fell to Mao Tse-tung in 1949; events in Vietnam were moving towards the fateful battle of Dien Bien Phu; by 1950 the Korean war had erupted. And the military struggle in Korea had two momentous economic effects.

Japan, forbidden at the Potsdam conference ever to become a military power again, now experienced a huge industrial boom by supplying the United Nations forces fighting the communists in Korea. The war gave the Japanese the beginning of their post-war revival and a take-off for their "export miracle." From that point they did not look back.

However, the other effect was a crisis for Britain's Labour government, still trying hard to build "socialism" in this island while completely at the mercy of the capitalist world outside. The war sent a shock wave of rising commodity prices through that world, to which a social democratic government had tied Britain for doctrinaire reasons, and thus right into the island economy. They had learned nothing from the fall of MacDonald in 1931. Britain, weakened by the war, now suffered a serious payments crisis and an upward spin in the spiral of inflation. Lord Attlee blamed certain "external factors" for his government's problems. He was right -- but they served to show that all such governments remain at the mercy of international forces they cannot control.

None of this surprised Mosley. He had shown where Labour's Achilles heel lay twenty years before in his speech of resignation from the MacDonald government.

His reaction to such events was always to give a constructive solution, and this time the solution was so far-reaching that all contemporary figures have utterly rejected it; in any case it challenged the whole structure of their international system of trade and finance established five years before at Bretton Woods under such glittering edifices as GATT, the IMF, and the World Bank. (They are not quite so splendid today, as their international system groans beneath world-wide recession and immense debts.)

What Mosley proposed, at another great East London meeting in December 1950, was the "division of the world" into several separate systems, each with a very large part of the world.

Each of these economic blocs, he explained in later speeches and writing, would have a big population as its market, adequate raw materials for its industry, and sufficient food. By insulating itself against the shocks of sudden movements in prices (what he called "the world cost system") its internal economy would be impervious to such shocks. Each economic bloc should concentrate on solving its own problems; it would be freed from the need to export, or import, since it would have all it needed within its own "borders." Within those borders a high standard of life could be built for its own people.

Mosley proposed that one such area, or bloc, should be formed from a fully united Europe, including Britain and the former Dominions; America should form another; a third should be formed in Asia around Japan. Had this idea of several "continental systems" been acted upon thirty years or so ago, today's problem of Japanese "laser beam" import drives into our markets would not exist: Japan's market would be in Asia. Nor would America be talking of a trade war with Europe. Europe, America, and Japan would be living at peace with each other in separate systems with economic areas big enough for all their needs. One might call this autarkic, not interdependent, "trilateralism."

The danger today is indeed trade war and for the obvious reason: nothing effectively had been done to avert it. Mosley's proposal would have ruled out trade wars; since governments failed to adopt it we can expect the consequences of this failure to act. More importantly, however, the same proposal of creating several large blocs in the world would make more unlikely a shooting war with either of the two communist powers, Russia and China, for Mosley emphasized from the start that no such bloc should interfere with any other, non-communist or communist.

What, though, of the men in the Kremlin who are still possessed by the messianic dream of communizing Europe as a step towards their world utopia?

True to its character as the restored empire of Ghenghiz Khan, the USSR always looks to further expansion, and a still badly-divided Western Europe is prone to a gradual take-over by the "splitting" tactics in which the Kremlin excels. Again, anything which weakens NATO or "splits" America and Europe only strengthens their hand. Further east, their occupation of Afghanistan is undoubtedly a stage for future inroads into Pakistan and India, when the time becomes ripe, or into Iran and the oil-rich Gulf -- always, however, under the guise of peaceful intentions. Churchill, in his days of barnstorming against early Bolshevism, used to speak of containing it by "a cordon sanitaire garnished with German bayonets," but matters have gone beyond those simplicities.

What is needed to contain the relentless Soviet expansion are Mosley's continental blocs, adequately armed to prevent Red Army incursions, with truly reinvigorated economies and social systems in which the appeal of communism withers, and above all imbued with a political idea far superior to communism.

The existence of just three such strong blocs in the world -- Europe, America, and Japan -- would bring the men in the Kremlin hard up against a new reality, sharply reducing the danger of new adventures, even in the stormy Middle East. And then real discussions could be held at the highest level between the leaders of the communist and non-communist powers, to secure an effective peace.

Mosley's was not a policy for war against Russia, but the very opposite. He showed this clearly in 1956 when he urged the reduction of tension between the Soviets and the West by taking up Khrushchev's offer, repeated several times, of Russian troop withdrawals from Eastern Europe if the Americans also withdrew from Western Europe. Whether the Soviet leader's offer was genuine or not should have been put to the test through hard and searching probing in direct negotiations. Mosley's answer to all such offers was "Get into the ring with the Russians."

He would take the same line today over Soviet proposals for cutting East-West missile strengths: hard and continual negotiations to reduce the danger of a nuclear holocaust. In his last, short, speech before he died in 1980 he called for such action to "stop the world being blown up."

He was thus following an old road in the fifties, but now going further. He had seen the high ideals of 1918 dashed as the war camps arose in the thirties, and in The World Alternative of 1936 proposed their reconciliation through a new settlement in Europe. Now, from 1950 onwards, he urged another and greater settlement of world problems, by the creation of several self-contained blocs, the purpose of which was both to abolish trade war and reduce the dangers of a nuclear conflagration.

It was in those years that Mosley took on his final historic roles as the man of world peace and as the forward-thinking economic European. If his ideals of 1918 carried him through to the end of his life on the quest for peace, a similar straight line can be traced through his economic ideas. His main goal here was so to organize society that the people would be enabled to consume what their industry produced.

Power of industry to produce had always been greater than the power of the people to consume, and Mosley thus advanced policies to redress the balance.

Thus, shortly after joining the Labour Party, he wrote Revolution by Reason, which propounded the idea of raising the living standard of poorer sections of the community by means of consumer credits, injecting purchasing power where it was needed most. Extra ability to consume in the hands of millions would raise demand until production was equated with consumption. Naturally, the government issuing the credits would take care not to inflate.

Again, in his Fascist period from 1932, he sought the same end by building up the home market through a higher wage policy within the corporate state. His basic reasoning remained that of his Labour days. "In organizing production we have to think, not so much of maximum output, as of maximum consumption," he wrote in The Greater Britain. British industry would not suffer from undercutting by cheaper imports when it paid higher wages, because each industry would be protected on the home market, on condition that the industry modernized itself. This he called "scientific protection."

After 1945, however, the problem became more complex. In winning the war many scientific advances were made, and when applied to industry after the war these advanced greatly the power to produce. Yet there was no advance towards a new-style consumption policy. On the contrary, weak governments turned to an old-style inflation. This brought its own evils: a decline in the power of the pound, a rising cost of living, and strong sectional power in the hands of trade unions. The devaluation trick only made matters worse. All imports then cost more, the cost of living rose again and wage-inflation duly followed, with the result that any export advantages from a depreciated pound were wiped out. For a Britain living by exporting this was a deadly drug.

Yet long before the opposite policies of deflation and the strong pound were tried, the march of science and technology was preparing an entirely new phenomenon in the power of industry to produce. It was known as "automation."

Mosley had long been familiar with the mass production methods he had seen on his visit to America in the twenties. During the thirties, rationalization was taking place, the displacement of men's labor by better machines. By the fifties automation was on the horizon and this, he wrote in an essay in 1955, threatened "not merely displacement but the virtual elimination of men's labor, because its machines will require only the services of a few specialists."

The danger to the whole of industrial society was that "under the old economics these few specialists would draw enormous wages and the rest would be unemployed. No market would then exist for the ever-increasing products of the machines, which would pile up in the midst of a surrounding waste of poverty." This was "the logical reduction to absurdity of a system which had never devised any effective means of distributing the wealth which modern science can produce." It was precisely the same problem which had led him to write Revolution by Reason -- but now much graver.

Thus in his 1955 essay, and in greater detail in Europe: Faith and Plan three years later, he outlined his solution: the "wage-price mechanism."

This was a policy for the deliberate raising of wages and salaries in the primary industries and the multiplying services in order to create an adequate market for manufacturing industry as it turned to automation. Two other things would be required: a new type of government in charge of the policy, working with the unions and the managers throughout, and "the insulated self-contained area freed from the world cost system." The large self-contained area was needed to provide a really big market for the immense potential of the automation age . Half-measures under the old economics could not cope. If government at present attempted to raise railwaymen's wages, for instance, this would "throw the whole system out of gear because additional transport charges would be added to the price of export goods." On the other hand, under new economics of the self- contained continental system which did not need to export, "it would be quite possible to raise wages far above the present level in all primary industry and services -- in agriculture, mining, power, building, banking, insurance and the Civil Service -- provided that automation in manufacturing industry had suddenly increased the power to produce; naturally, only on that condition."

As a variation of this great increase in wages there could be a planned shortening of hours, a three- or four-day week in work-sharing schemes, creating many jobs for the unemployed. Or there could be both higher wages and shorter hours.

Once automation spread to all manufacturing, with greater volume of output balanced by higher wages and shorter hours, the whole expansion taking place within an insulated continental system, Mosley foresaw greater possibilities still. Governments operating his wage-price mechanism could then draw workers to any industry or service short of manpower. If more miners were needed, raise their pay. If more food was required, raise the farmer's reward, to take on more labor or to buy better agricultural machines. If education was short of teachers, then increase their salaries. And if some branch of science or technology needed extra personnel to advance it, once proved to be beneficial after thorough tests, rewards should be raised. Indeed, he continually stressed that science and technology should always come high in the scale of rewards; skilled workers should come before the unskilled in industry.

"We will not direct men to do what is necessary in the common interest, but we will pay them to do it so effectively that, in fact, they will do it, and the increased productive power of automation will give us the means to pay them," wrote Mosley in 1958.

Yet could the wage-price mechanism be introduced in a small island like Britain before the great area of a united Europe was formed? Would it work in a Britain faced with high unemployment and serious inflation? It could, Mosley wrote: it would then "also be necessary to fix prices over a wide field." This second form of the wage-price mechanism is needed indeed in the Britain of 1984. Shortening hours to a three- or four-day week in work-sharing schemes would mop up unemployment; direct action for fixing prices over a wide field would curb inflation, and these measures would be strengthened when wider use of automation in Britain would cut prices anyway.

If the present work force in manufacturing worked half the working week, another work force of about the same size could be recruited from the unemployed to operate the same machines for the other half of the week. That is the way to get unemployment right down and raise output. The market to consume the bigger output would be provided by raising wages generally throughout the whole economy. That could be done in Britain alone, with government, unions and managers acting as a team to organize the policy; yet how much more effective it would be if the same policy was in operation throughout Europe, as Mosley emphasized.

This was his wage-price policy long before Mr. Heath tried a "pay freeze" in the early seventies and Mr. Wilson experimented with his "social contract" a few years later. Mosley's policy was positive; theirs were negative. His wage-price mechanism was to be a permanent instrument of economic management while theirs were merely short-term expedients, soon abandoned. There could be no comparison whatever.

Thus it is nonsense for Mrs. Thatcher to say that "all" wages policies have failed. Certainly all negative policies have been tried, and they failed. What has never been attempted is the wage-price mechanism of Oswald Mosley.

Above all other questions, however, is that of the type of government needed to make these changes. Mosley was deeply concerned with this question in his Labour days, being much impressed with Lloyd George's inner cabinet of five men with wide powers which had won the First World War, and in his Memorandum proposed a "machinery of government" to modernize industry and solve unemployment. Lloyd George had overcome huge wartime problems in 1917, but a Labour government collapsed in 1931 when faced with lesser problems of peace.

When founding the British Union of Fascists, Mosley addressed himself to the paradox of a British democracy which could fight world wars with governments of action yet failed before the test of economic crisis in peacetime. He pointed out in The Greater Britain that the system of government was a century out of date in 1932 while the country had changed beyond recognition during those hundred years.

Nevertheless, no attempt was made by the ruling politicians of the thirties to remedy the situation, and the paradox was seen again in another world war when Churchill copied, to some extent, the methods of Lloyd George. And again, with 1945, the habits of peacetime returned. Party rivalries reasserted themselves; the time-wasting procedure of Parliament was treasured once more like some precious national heirloom. Britain's problems were worse than ever, yet Parliament, far from becoming an efficient workshop to face a more serious age, resembled on some days a slumbering museum and on others a beer-garden. And all the world stood amazed at that ancient ritual of M.P.s dragging a new Speaker to his seat!

Little wonder that Britain has gone down-hill ever since under the vast weight of innumerable points-of-order and obstructionisms.

By 1966, Mosley could say without any fear of contradiction that the old party system was, to all intents, bankrupt. In Action he wrote: "Labour and the Tories have failed equally; the Liberals have no answer at all. No matter which is in office they cannot cope. The only way is to go above and beyond the parties to a national union of the best of our people" and to form "a government of true national union drawn from the most vigorous parts of the whole nation." A government drawn from "the professions, from science, from the unions and the managers, from businessmen, the housewives, from the services, from the universities, and even from the best of the politicians."

It would be a new-style government of action with "hard centre" ideas and not an old-style coalition of soft center politics, elected for one term of office with the specific task of putting Britain on its feet. It should gain from Parliament the power of rapid action under an Enabling Act, so that the time-wasting obstructionism of present procedure would be removed.

Parliament would always retain the power to dismiss it by vote of censure if its policies failed or if it attempted to override basic British freedoms.

This would make for the utmost action within the constitution, and it was precisely how British governments functioned during the emergencies of two world wars, except that such a government would be drawn from the whole nation instead of merely from the parties. In Mosley's phrase, this was "using the methods of wartime to solve the problems of peace," bringing to an end that paradox of government of well over a century in Britain.

It is said that Oswald Mosley was a man before his time, and there is some truth in this. His life was spent in a Britain where big parties occupied the arena and held the devotion of millions, no matter how many their failures. Those parties had become the political armies of the class system, and the Mosley who placed nation before party and valued the individual for his abilities, not his class background, was in that sense a man before his time, the time when the parties would decline through their own shortcomings and corruptions.

To turn his back on the party system when the faith of millions in it was still unshaken, to go "out into the political wilderness," was therefore regarded as effective suicide. For the millions who took their opinions from the party leaders, those politicians represented public opinion, whether Stanley Baldwin with his pipe and his pigs and his limpet-like philosophy of "safety first"; or Harold Macmillan, who was also trusted because Britain had "never had it so good" and could have it better with the Tories; or Harold Wilson, who was trusted less but knew how to "keep his options open."

Mosley was of another world to these. He stood for action (that word so uncomfortable when things looked good and would get better). He advanced policies which would be needed when the spell of the parties had been broken in a nemesis brought by their failure to change. When Britain faced reality at last, that second great crisis he had long predicted came with a vengeance.

Now it remains, but much has broken down in Britain since 1930, from the loss of faith in politicians to the ominous decline in law and order.

The dangers in such a long decline were seen more than fifty years ago by Mosley himself. "What I fear," he warned in his Resignation Speech of 1930, "what I fear much more than a sudden crisis is a long, slow crumbling over the years, a gradual paralysis beneath which all the vigour and energy of this country will succumb. That is a far more dangerous thing, and far more likely to happen unless some effort is made. If the effort is made, how relatively easily can disaster be averted..."

That call for effort made him less a man before his time than a man of the moment, devising policies to meet an immediate situation, which he did again at several moments in his life.

To get Mosley into true perspective: he was both a man of the present and of the future. But Britain has lived in the past increasingly, lured by those siren songs from the Palace of Westminster, those delusions of grandeur which alone remained after the sun of Empire set, those voices of the media constantly invoking the name of Churchill while silent over the destruction brought about by Britain's most disastrous leader.

Hence the gap between Mosley and his countrymen. The latter are left with the crumbling and paralysis against which he warned.

Yet there was more to it than that. There was the deep-seated hostility of those in authority collectively known as the Establishment and who, as Richard Crossman wrote, spurned Mosley because he was right. What was there about him which so much alarmed them? Was it, as the caustic Bernard Shaw remarked, that he "looked like a man who has some physical courage and is going to do something, and that is a terrible thing"? Did he have too much driving force for the men of lethargy in high place -- -had he too much of the air of Sir Walter Raleigh for the smooth prototypes of late- 20th century British authority, the mandarin and the pundit?

Was he altogether too disturbing a personality for those who preferred a "safe" career and easy weekends in the Indian summer of national greatness, crowned by a place in the Honors List? Was it, as Drennan noticed, that he was a man "of strong tones, no self-complacent bladder of conventions," whereas conventional politicians were easier meat, posturing amid growing decadence according to long-established rules?

And what of his policies? It has become fashionable to praise them. For instance, A.J.P. Taylor acclaimed the Memorandum as offering "a blueprint for most of the constructive advances in economic thinking to the present day." High praise; why was that thinking not carried into effect? If Mosley himself was too unorthodox to be entrusted with accomplishing his own ideas, why was not some other figure entrusted with them, one of those "safe" politicians whom the Establishment trusted?

The fact was, as Michael Foot observed, that "mediocrity and safety first" stood in the way not only of the man but also of the policies. Yet failure to act never solves problems. Avoiding early effort only makes the effort more strenuous if the problems, now grown huge, are not to overwhelm society. A long run of good luck and the peculiar delusion that the Almighty is really an Englishman have encouraged the national vice of "muddling through." The luck is running out now, and the problems stand there in gigantic proportions.

What next? How soon will there be a murmur rising higher for a man like Mosley, his dynamic approach to life at last forgiven? But men like Mosley are rare. Will one emerge, as the great voice still echoes down the years, calling "Britain awake"?

----------------------------------------------

From The Journal of Historical Review, Winter 1984 (Vol. 5, No. 2, 3, 4), pages 139-165.

Click on this text to see Oswald Mosley giving a Fiery speech at a Manchester blackshirt rally...  Oswald Mosley – An Inspiration for 21st Century EuropeEurope A Nation‘Europe’ is more than an economic region from which bloated bureaucrats and political

nonentities draw salaries and perks. Before the conniving Count Kalergi and his banker friends, and before cabals such as

the Bilderberg Group, there was ‘Europe’ as a living, dynamic organism, whose culture, faith, and heroes have

been smothered in a quagmire of American junk culture, the debt of bankers, and the opportunity for the sweepings of the

world to call themselves ‘Europeans’. ‘Europe’ has been hijacked and besmirched by outer enemies

and inner traitors.

Paradoxically, the Europeans with the soundest instincts are among those who reject and oppose the entity that is today called ‘Europe’, as the recent Brexit poll indicated. However, such has been the disgust at the European project as manifested by secular-humanists, Masons, bankers, bureaucrats and U.S. geopolitical strategists, that the noble Idea of Europe-a-Nation, unfolding over the course of centuries, has been replaced by those who should be promoting it most avidly with the petty-statism that was inaugurated by the French Revolution and subsequent liberal forces of disintegration. Europe has been turned into a travesty of herself, and spurned by those who should be her champions because they are not seeing beyond several hundred years of treachery, corruption and culture-sickness.